DONIZETTI MUSEUM

Bergamo cherishes the memory of its most famous composer, Gaetano Donizetti. No one could have imagined that the third son of a poor artisan living just outside the city wall could have risen to such international renown. But thanks to the help of Johann Simon Mayr, the German-born maestro di cappella at the basilica of S Maria Maggiore, his talent was quickly recognized and nurtured. Fired with creativity and soon much in demand for new operas in Naples, Milan and later Paris, where he gained Rossini’s favour, fortune beckoned. But his life, in some ways like a fairytale, ended sadly: a melancholy widower whose children had all died in infancy, mentally debilitated by syphilis, paralysed and unable to speak, he returned from Paris to Bergamo in 1848 to die among family and friends.

Donizetti was born on 29 September 1797 in a dark, two-room apartment below the street in the Casa Codazzi, at Borgo Canale 10 (now 14). The street winds down the slope of the alta citta -the old part of the city is built on a steep hill – from the S Alessandro gate towards the Lombardy plain below. Donizetti’s birthplace was declared a national monument in 1926 and in 1994 a modest exhibition, Donizetti a Bergamo’, opened there, showing photographs of the city and a variety of posters. Yet it does evoke the conditions under which Donizetti spent his early years, cramped and dank. (The family shared a kitchen and laundry space with other families resident in the basement.) The upper part of the house is now occupied by the Fondazione Donizetti. A few doors away a plaque marks the house in which the cellist Alfredo Piatti, himself a great admirer of Donizetti, was born in 1822.

Istituto Musicale Gaetano Donizetti, Bergamo

The family fortunes changed in 1806: they moved to better quarters at Piazza Nova 35 (now Piazza Mascheroni 8) and Gaetano began studies as one of the first pupils at the choir school revived by Maestro Mayr that year. When Donizetti was 18, Mayr made it possible for him to continue his studies in Bologna at the Liceo Filarmonico Comunale, after which he returned to Bergamo and on Mayr’s recommendation obtained commissions for four operas for Venice.

DONIZETTI MUSEUM Photo Gallery

Naples in the 1820s, Milan in the early 1830s, and then Naples, Vienna and Paris – not Bergamo – were in turn his home. He married Virgilia Vasselli in 1828; she died in Paris in 1837. Ominously, in 1844 the first signs appeared of the cerebrospinal degeneration’ diagnosed two years later; after 17 months in a suburban sanatorium at Ivry he was reduced to semiconsciousness, unable to move or speak. His nephew brought him home to Bergamo, where he died six months later, on 18 April 1848, in the Palazzo Scotti. The house, at what is now Via Gaetano Donizetti 1, is marked by a plaque. Donizetti was initially buried in the Pezzoli family chapel at the Valtesse Cemetery. But in 1875 his remains, along with those of Mayr (who had died in 1844), were exhumed and interred in S Maria Maggiore; Donizetti’s tomb was topped by a monument sculpted for the basilica by Vincenzo Vela in 1855. In 1951 the city fathers decided to re-open his tomb a second time to unite the cap of his skull (retained by a pathologist as a souvenir of the autopsy) with the rest of his remains. With the centenary of Donizetti’s birth in 1897 came the first exhibition in Bergamo of his memorabilia, drawn from the collections of his brother’s grandsons.

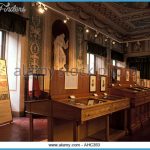

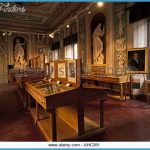

This may in turn have inspired the foundation of the Museo Donizettiano in 1903 by Baronessa Scotti, who endowed it with her own collection. The museum, among the finest of its kind in Italy, occupies two rooms in the Istituto Musicale Gaetano Donizetti, the successor to Mayr’s school (Mayr lived nearby, at Via Arena 20). The collection is by any standards extensive, and that enables the displays to be regularly changed. There are musical autographs from 1813 onwards; letters and other documents; innumerable portraits of Donizetti, Mayr, his family, friends (especially the baronessa) and his singers; his pianos, including the 1822 Carl Strobel that he used for composing most of his music and his 1844 Bosendorfer as well as Mayr’s Caspar Lorenz square piano; and the Austrian court clothes he wore as Kapellmeister in Vienna in 1842. All the manuscript texts on display are clearly transcribed. Entire cases are devoted to individual operas and illustrated with scene designs, printed scores and librettos as well as manuscripts and portraits.

There are also personal effects – quill pens, his toilet kit, his Turkish pipe, his ring and Madonna medallion – and a death mask. Among the most graphic images of the composer is a daguerreotype portrait of him, ravaged by illness, with his nephew at Ivry, dated 3 August 1847. Until 1951 the cap of his skull was displayed in an urn; perhaps even more macabre, the museum also owns the black wool tailcoat in which he was buried and which was recovered almost intact’, in 1875. In an alcove off the main room are furniture and mementoes of his last days, including his invalid’s armchair, with a tray and upholstered headrest, and the bed in which he died. On the wall is a telling, but dignified, idealized last portrait by Giuseppe Rillosi (the invalid chair lacks the tray and headrest).