This is definitely one for the boys of all ages. Actually, when we visit the Minsk, the picture is always the same; confident and excited males followed, never led, by women who are tolerant at best and occasionally in active opposition.

The Minsk is the former flagship of the Soviet Pacific Fleet. It was built at the Chornomorski Shipyard at Nikolayev on the Black Sea and commissioned in 1979, and from its base in Vladivostok it freely sailed the great ocean, or so the blurb at the park tells us.

At 42,000 tons and 275 metres long, it is classed as a medium sized aircraft carrier. Depending on the source you read, it appears to have carried between 32 and 42 aircraft. Equally unclear is its later fate. Some say that it was involved in an accident, others that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian government was financially incapable of maintaining it. In any case, by 1998 it was in the hands of a South Korean ship breaker.

From there on the story of the Minsk becomes a very Shenzhen story: a little intrigue, a cast of colourful characters, a bit of creative financing, a bust, a heavily managed market-based rescue and plenty of razzamatazz.

In 1998, a group of unidentified Chinese businessmen approached the ship breakers and proposed a purchase of the Minsk. There was a deal of discussion at the time in the press suggesting that the businessmen were a front for the Chinese military and that they wished to use the Minsk as a model in their own design work for a Chinese aircraft carrier. The Koreans made it clear that they had stripped all sensitive military equipment from the ship, and in any case a condition of sale would be that the ship should not be used for warlike purposes.

At this stage the D’Long Group entered the picture. The D’Long Group, based in Xinjiang Province in western China, was the vehicle of the Tang brothers, Tang Wenxin and Tang Wenli, who were generally viewed as paragons of the new Chinese entrepreneurial class. They boldly announced that the Minsk would be towed to Shenzhen where it would be the basis of a naval and military theme park. To finance this they put together a package, which, in the best traditions of modern Chinese finance, involved more than the usual amount of smoke and mirrors. Total investment was reported as being $500 million.

The Minsk World theme park opened to great public clamour in September 2000. Up to 5000 people a day paid $100 to visit the park and during the week-long National and May Day holidays as many as 110,000 visitors went through the ship. Between September 2000 and 2005, the park was reported as having turned over $450 million. This should have been enough to support even the most heavily geared financing but in 2005 China Construction Bank claimed that its $200 million loan to the park was not being serviced and applied to the Guangdong Marine Court for a winding up of the business. During the proceedings it was not made clear where the cash flow of the business had disappeared to, but it apparently was not to the lending banks, and the court ordered the park to be auctioned off. Meanwhile, the visiting boys continued to fire off automatic weapons in the shooting range, the Russian dancers continued to kick up their heels on the stage which had been set up in the main deck hangers, just next to the Su 27s, and boys of all ages continued to crawl over the fighter jets and helicopters, and stare longingly at the captain’s cabin.

There was plenty of interest in buying the Minsk. At the sort of prices being talked about, and with the sort of visitor numbers which continued to turn up, an investor would have his money back in a couple of years. But for whatever reason the Shenzhen City Government wasn’t about to let things go through that easily. It was made clear in the world of Chinese finance that whatever the courts might think, the ownership of the Minsk was not going to leave Shenzhen, nor was the ship. This was not encouraging for most bidders and the first auction failed to attract a single bid.

Behind the scenes the City Government worked in a frenzied fashion and found both its buyer and its market level. Rumour had it that CITIC Shenzhen, the local branch of the China International Trust and Investment Company, had been convinced that it was in everybody’s interest if it were to make a bid and, on 31 May 2006, when the auctioneer opened bids, there was one bidder who took the prize at the, some would say, carefully negotiated reserve price of $128 million, a bargain.

So now it’s not Minsk World. Little yellow banners all over the park tell you that it’s very definitely CITIC Minsk World.

The park is divided into two parts, a land based series of games and exhibits, and the ship itself. As you enter the park and proceed towards the main building, a slightly shabby Russian 19th century style building, you are confronted by a 40-foot high piece of socialist realist sculpture. The sculpture is a replica. The original, by the Soviet sculptor Vuchetich, stands in the forecourt of the United Nations in New York. It is supposed to represent somebody, doubtlessly a worker, beating swords into ploughshares that is why, at Minsk World, it is the centrepiece of Peace Square. But socialist realist sculpture always leaves us thinking of altogether more aggressive matters. Most locals we spoke to were convinced that the large naked Russian figure was actually making weapons. Decide for yourselves.

After this nod to Sino-Soviet friendship, we get down to the real essence of the thing, i.e. being a boy. There is a terrific shooting range where you can shoot BB guns. The kewpie dolls offered as prizes seem a bit incongruous really. Then there’s all manner of military hardware, an amphibious tank, some heavy artillery, and a Soviet military helicopter. The serious business of the park starts on the ship. Not a lot of real military stuff is left. Remember that the Koreans stripped it all. But we thoroughly enjoyed the displays of historical models and pictures of aircraft carriers, and were interested to see that Japanese World War II models prevailed. The Sino-Japanese relationship is never a simple matter. We also enjoyed going up to the bridge and through the Captain and Officers’ quarters.

A couple of allegedly Soviet aircraft sit in the hangars along with some attack helicopters on the deck they look forlorn and, given what we had heard about the Korean sales conditions, we were inclined to think of them in the same terms as the sculpture in Peace Square, replicas. Still, we are in Shenzhen and things aren’t always what they might appear. All in fun.

Deck 5 as you enter the ship has been converted into a stage for dance shows presented by Chinese and Russian troupes and the Cossack-style Russian dancers impress with their discipline and general vigour. There is also a display of Soviet space achievements that are worth a look.

All in all, lots of fun for boys. Entry is $110.

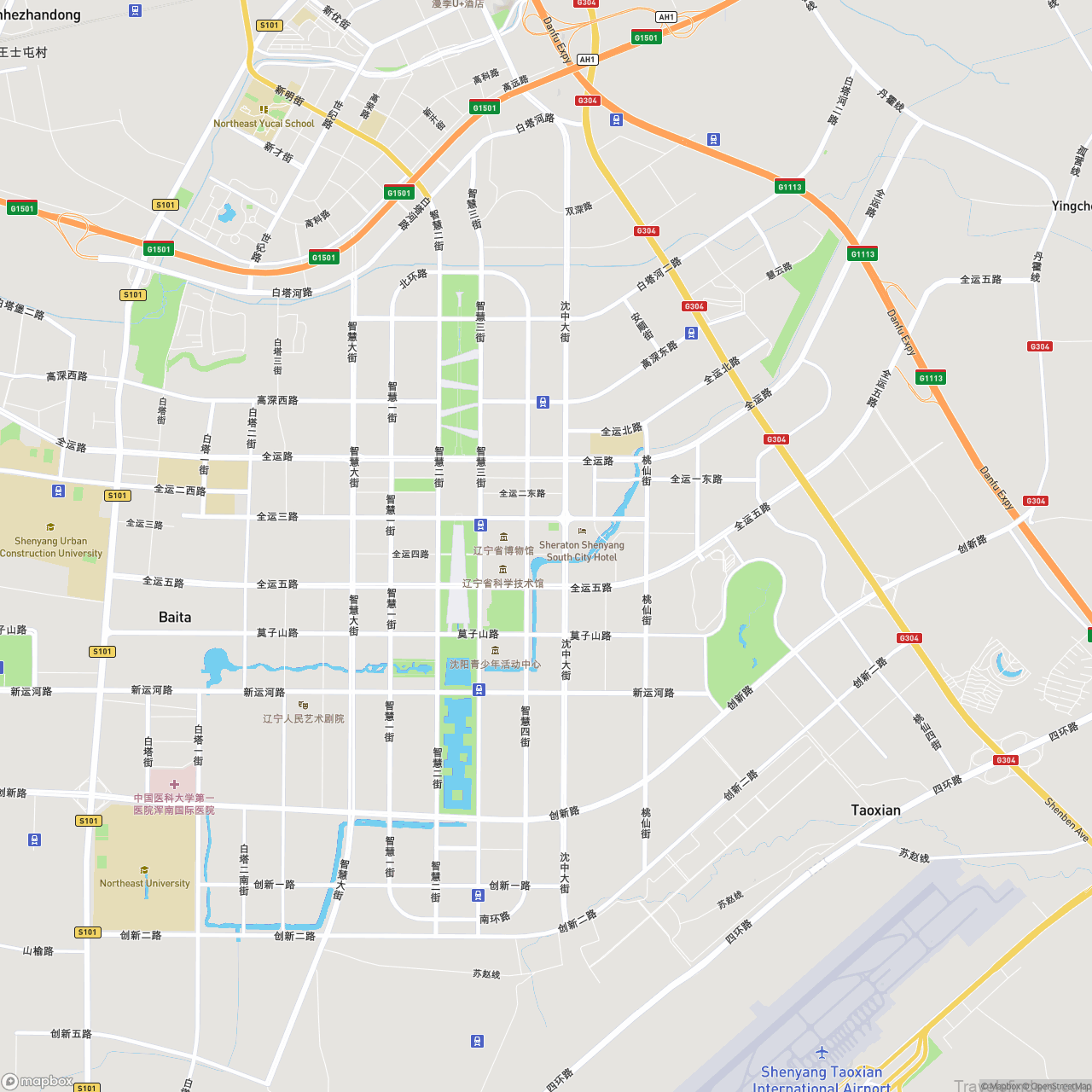

Address: Jinrong Rd, Shataukok, opposite the Yantian District Government Building.

Open 9.30 am 7.30 pm

Bus nos. 103A, 202, 205, 239, 358, 360

Bus Stop Hang Mu Shi Jie