At the conclusion of the French and Indian War, known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe, the British extended their rule across French Canada and

into Florida through the 1763 Treaty of Paris. In this process, they encountered significant problems with Native Americans, who had preferred French

colonial policy and mistrusted British intentions.

After suppressing Pontiac’s Rebellion, the British needed to formulate a plan to keep the peace on the frontier and maintain the loyalty of the Native

Americans. The Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on October 7 from his court in London on the advice of Secretary of State Lord

Egremont and President of the Board of Trade Lord Shelburne. It attempted to mandate a solution to Native American mistrust and establish British rule

over the new lands. A limit to settlers spreading over the Appalachians had already been implemented by Colonel Henry Boquet in 1761; that decision

provided a useful model for the proclamation.

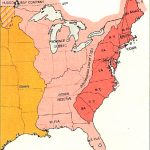

The proclamation formally annexed the French islands of Cape Breton and St. John’s; expanded the colony of Georgia between the Alatamaha River and

St. Mary’s; and set up four new imperial government units in East and West Florida, Quebec, and Grenada (the Caribbean Grenadines), including all the

associated royal officials and their powers. Veterans of the French and Indian War were granted land, preferably in the three new continental British

possessions, based on their ranks, ranging from field-grade officers receiving 5,000 acres to a private soldier’s claim of 50 acres.

The proclamation also forbade further British settlement west of the Appalachians or beyond the headlands of the rivers flowing into the Atlantic Ocean,

effectively keeping the white population on the East Coast. Those lands to the west were considered the possessions of the Indians, and all but royal

officials were forbidden to grant claims or to purchase any of it, as Native Americans were under the personal protection of the British monarch.

The proclamation stirred heated feelings amongst the colonists, many of whom had quickly taken advantage of the peace to buy up western land claims

that were now worthless. Colonial celebrities such as Washington, Franklin, George Mercer, and the Lee family were heavily invested in land

speculation in the rich Ohio Valley, and their fortunes suffered because of the royal decision.

Colonists believed that the king and his ministers wanted to keep the settlers close to the coastline because this made them easier to tax and police,

although Shelburne hoped that the westward limit would help to encourage the settlement of Quebec and Florida. The colonists were also angered by the

privileged position granted to Native Americans, including additional royal regulation of the fur trade and the prohibition of the sale of rum or rifled

weapons to the tribes. Royal Indian agents threatened the trade conducted by colonists and cut off their ability to make quasi-legal land transactions.

For the British, the Proclamation of 1763 made good sense. It offered the tribes proof that Britain would honor its claims to essential hunting grounds and

protect them from fraud and underhanded business dealings both were much-missed protections under the French royal officials. Ideally, the

proclamation also would encourage the colonists to settle in underpopulated areas of the Eastern seaboard before pushing inland to areas where there

would likely be conflict with Native Americans.

The Proclamation of 1763 was meant as a temporary halt to colonial expansion, pending investigation and governmental regulation. It was followed up in

1764 by a more precise drawing of the western boundaries of the individual colonies, largely the work of the northern and southern Indian agents Sir

William Johnson and John Bruce, along with elaborated rules for colonial dealings with Native Americans. The problem was that settlers already in the

forbidden areas refused to leave, while new immigrants crossed the borders in spite of the proclamation, triggering continual problems with the tribes, as

their promised lands were encroached on. More fraudulent deals also took place for the purchase of land.

The British responded by stepping up their presence in the former French chain of frontier forts and constructing more defensive works along the line of

the proclamation. The expense of these fortifications, which seemed pointless to the colonists without the French as an enemy, triggered many of the tax

demands that fueled the American Revolution.

Margaret Sankey

See also: Appalachia; French and Indian War; Land and Real Estate; Maps and Surveys; Ohio Country.

Bibliography

Abernethy, Thomas. Western Lands and the American Revolution. New York: Russell and Russell, 1959.

James, Alfred P. George Mercer of the Ohio Company: A Study in Frustration. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1963.

Johnson, Cecil. British West Florida, 17631783. Hamden, CT: Archon, 1971.

Sir or Madam: I have just finished drafting a book titled “Raised under the Rose: A Navigator’s Reflections on the Long Struggle for Canada’s Borders”. I hope that this will be a popular history of the various treaties and conventions that marked Canada’s territorial evolution from 1763 to 1930.

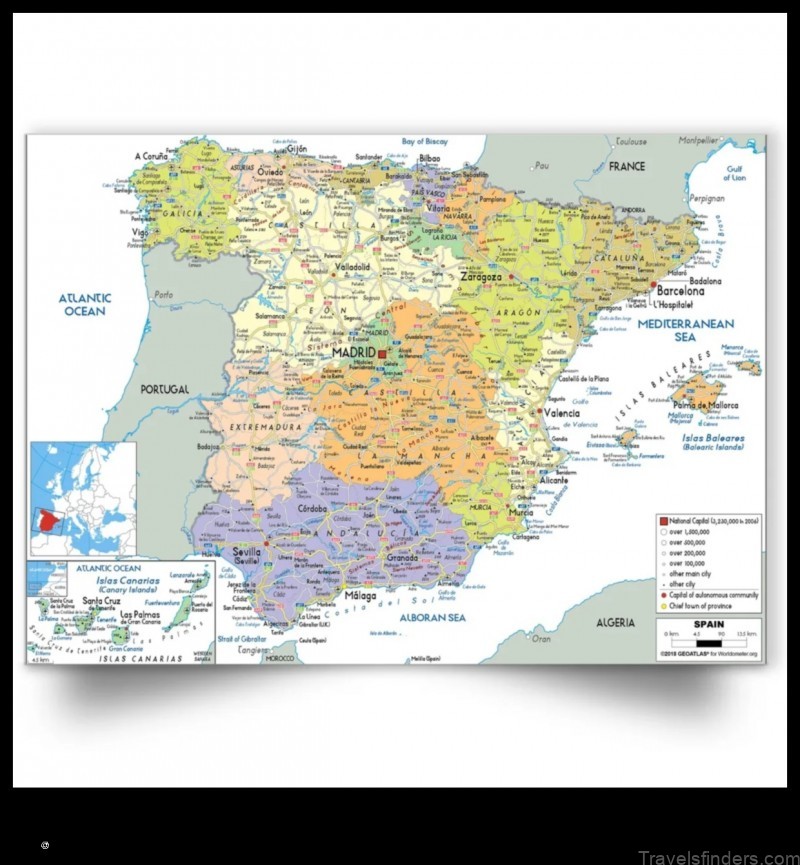

In the course of the research I was searching for a map illustrate the results of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. After reviewing several maps, I decided that I would like permission to include one of your maps in my work. It is above and is titled “The Proclamation Line of 1763”. I cannot find any identifying number.

For your kind consideration.

Allan E. Jones, 8 Queen Mary Street, Ottawa, Ontario, K1K 1Y2, phone 613-316-7095

yes u can use.