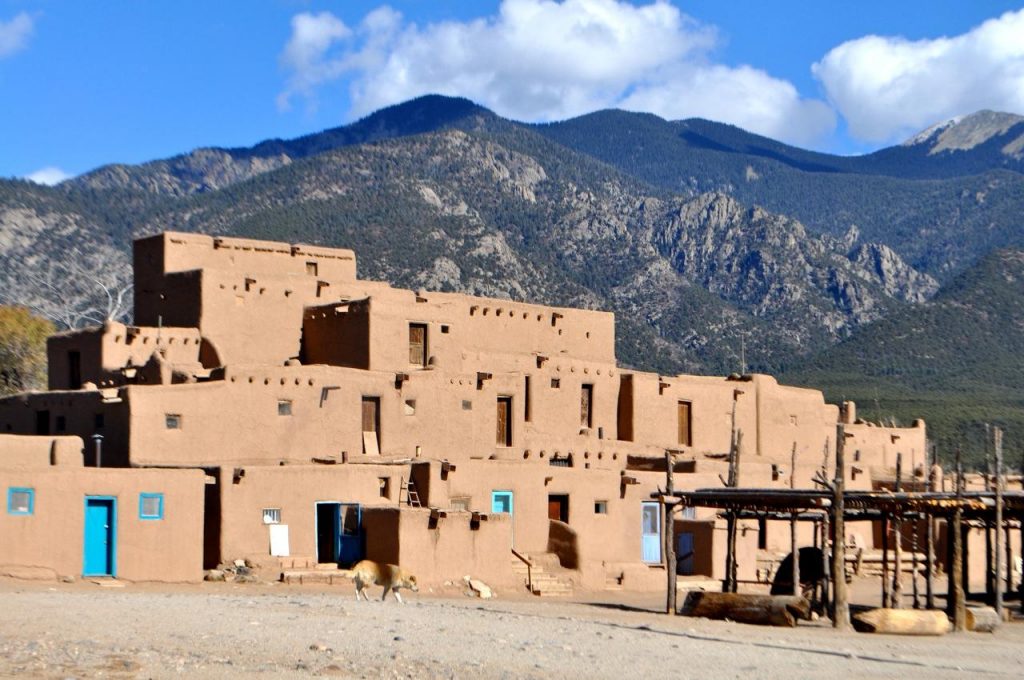

The Pueblo Indians describe their emergence from the underworld as having been like a maize shoot sprouting from the earth. Established in a number of

compact settlements on the semiarid Colorado plateau of northern Arizona and New Mexico, the pueblo developed a society based on agriculture and

distinctive arts and crafts held together by a comprehensive worldview and ceremonial system.

The men of every pueblo considered their town to be the center of the universe and placed the main kiva at the center of a sacred space that extended

outward in the four cardinal directions, upward to the four skies, and downward to the underworld. Rain was their central preoccupation, but all forces

were balanced and represented in Pueblo society. Maintaining that balance was the charge of the Pueblo people. The Pueblo form a nation in the

Southwest, despite divisions based on location, ecology, language, and social institutions.

Dating back over 1,000 years, the Pueblo settlement at Acoma is one of the oldest surviving communities in what is now the United States. Despite their

ancient presence in the region and their cultivated respect for continuity and tradition, the Pueblo’s culture was not static. In the years prior to Spanish

occupation, the Pueblo had learned to live in the region through raiding, war, immigration, and, most often, vast trade networks. When the Spanish

arrived, the Pueblo people, who conceived of their society as unfolding according to a preordained plan, were thrown into disarray.

The first information Spaniards obtained concerning the Pueblo came from lvar Nº±ez Cabeza de Vaca’s expedition, which traversed the area in 1528.

Inspired by their accounts, Fray Marcos de Niza, accompanied by native guides and an African slave named Esteban, who had been with de Vaca, led an

expedition into Pueblo territory. Met with hostility, the expedition returned to Mexico. Undeterred, the Spaniards launched another expedition under

Francisco Vzquez de Coronado in 1542. Seeking vast riches, Coronado returned to Mexico disappointed, and no expedition visited the Pueblo for the

next forty years.

Small Spanish expeditions returned to Pueblo territory by the 1580s; however, in 1598, Don Juan de O±ate led 400 Spaniards and Mexican Indians

northward into the upper Rio Grande Valley. The stability of Pueblo society and culture, as well as Pueblo achievements in architecture, agriculture, and

crafts, aroused Spanish admiration, but contact led to conflict.

Ill equipped for life in the Rio Arriba, the Spaniards placed heavy demands for food and tribute on the Pueblo people. This prompted rebellions by the

Tompiro, Tiwa, and Acoma in December 1598. The Spaniards crushed the rebellions, and, for the next seventy years, the Pueblo toiled under an

oppressive system, providing tribute and personal service to the Spaniards. Their settlements secure, the Spaniards dispatched missionaries to the various

pueblos, where suppression of native religious practices emerged as a point of contention.

The Pueblo settlement at Acoma, New Mexico, is the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States, dating back nearly 1,000 years. The

mission church, seen here, was begun in 1629. (Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Jesse Logan, N-67)

By 1680, the Pueblo had suffered droughts, overtaxing demands for tribute, increasing raids by their nomadic neighbors, and the suppression of their

religion. Seeking to free themselves, they devised a plan to expel the Spanish from their territory. Pueblo leaders planned to (1) cut Santa Fe off from

outlying communities, (2) send word to the Pueblo in the north and south of the fall of the capital, and (3) attack before the annual supplies from Mexico

arrived in the territory. The revolt exploded throughout the Pueblo territory, resulting in the deaths of twenty-one of the thirty-three Franciscan friars there

and 400 colonists. The remaining Spaniards fled back to Mexico. Thus, the revolt provided the Pueblo with an intermission of independence.

In 1692, just twelve years after their expulsion, the Spaniards returned with a new colonial system. Gone were the harsh tribute and labor demands, and

the assaults on Pueblo religion were tempered by moderation. By 1700, the Pueblo and Spanish had developed a tenuous peace. The Pueblo became

allies to the Spanish as raids from neighboring peoples increased in frequency. The Spanish ended the prohibition against trading guns, and enlisted the

Pueblo in the defense of the occupied territories on the Rio Arriba.

The Pueblo peoples’ desire for peace and harmony led them to declare truces during the summer and fall. During these truces, vast trading fairs were

held among the Native Americans. Sensing an opportunity, the Spaniards gave government sanction to these fairs in an effort to open communication with

the hostile groups.

Spanish protections ensured, the Pueblo began to recover some of their lost prosperity. By 1800, they had gained a secure position in provincial society.

Todd Leahy

See also: Missions; Native American-European Conflict; Native American-European Relations; Native Americans.

Bibliography

Gutierrez, Ramon. When Jesus Came the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 15001846. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press, 1991.

Milner, Clyde A. II, Carol A. O’Connor, and Martha A. Sandwiess, eds. The Oxford History of the American West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Sturtevant, William, ed. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 10. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 19782001.