Latinos in Tennessee, 1540-1950

Tennessee’s earliest documented European presence is the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto, who came in 1540 in search of gold. In 1541, De Soto and his European and black followers reached the Mississippi River in present-day Memphis. Twenty-five years later, in 1566, another Spanish explorer, Juan Pardo, came to Tennessee. Whereas de Soto left only violent memories among Tennessee’s Native Americans, Pardo constructed Tennessee’s first European-built structures and was the first to use the name Tennessee.

Although neither de Soto nor Pardo followed exploration with settlement, Spain continued to claim Tennessee as the Spanish Indies’ northern reach throughout the late eighteenth century. In the process, Spain influenced Tennessee’s landscape through trade relations with Native Americans, the survey system of metes and bounds, and its customs and place names, especially in West Tennessee.1

By the late eighteenth century, Spain had abandoned claims to Tennessee, but middle Tennessee entertained its own alliances with Spain. In the 1780s, concerned about being left out of trade negotiations over access to the Mississippi River and worried about Native American raids into white settlements, middle Tennessee turned to Louisiana’s Spanish governor, Don Estevan Miro, and opened a dialogue about Spanish allegiance. Spain was interested in middle Tennessee for both the area’s value in territorial struggles with Britain and the United States and its location as a barrier to westward-marching Anglo settlers. Middle Tennessee, on the other hand, was interested in Spanish allegiance as a bargaining chip with the U.S. government. In a show of commitment to this alliance, middle Tennessee’s Cumberland region was named the Mero District to honor the Spanish governor. That name, however, was the only claim Spain made on middle Tennessee, as Cumberland leaders successfully pressured the U.S. government and ceased negotiations with Spain.

Despite early Spanish influence in Tennessee, 200 years passed before Latinos would again affect the state directly. In the mid-nineteenth century, however, Mexico played an indirect role in Tennessee’s military activity. After the Texas

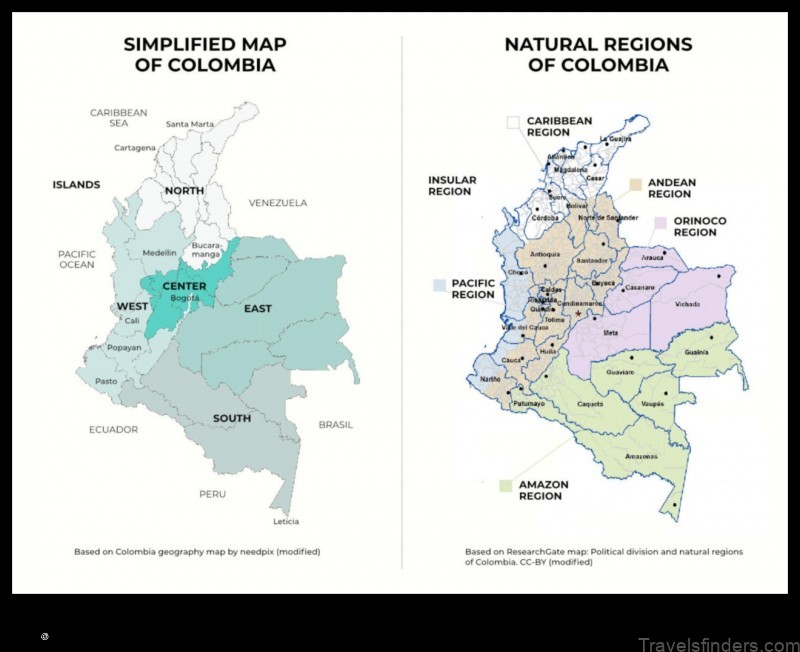

Revolution, many Tennesseans were sympathetic to Texas’s causes, volunteering en masse for service in the Mexican-American War. Evidence of their deployment can still be seen in Tennessee towns, such as Buena Vista and Cerro Gordo, with names recalling famous Mexican battle sites.2 This Latino influence in Tennessee stretches even farther south. In 1825, the town of Bolivar, Tennessee, was named to honor Simon Bolivar; and 1869 marked the founding of Brazil, Tennessee, after some community members emigrated to Brazil. From Bogota to Cordova, a handful of Tennessee towns bear Latin traces, even if Latinos were largely absent in Tennessee until the mid-twentieth century.