In the Iliad, to try to turn aside Achilles’ wrath over the loss of his slave girl and persuade him to return to the fighting, a Greek delegation reminds him of the battle at Calydon. In this version, Meleager, angry with Altheia, withdraws from the conflict outside the city, and stays at home with his wife Cleopatra, nursing his heart-aching wrath, in fury at his mother’s curses which, mourning her brothers’ death, she called upon him from the gods. Repeatedly she beat her fists on the rich earth, as she stretched out on the ground, her bosom wet with tears, calling on Haides and revered Persephone to bring death to her son; and the Fury who walks in darkness, whose heart is merciless, heard her.’ Meleager’s absence allows the enemy to gain the upper hand. As the situation worsens, Calydon’s elders offer Meleager magnificent incentives to return to battle; next his father, sisters and even his mother Altheia beg him to fight. But only when Cleopatra adds her voice does Meleager buckle on his armour, stride on to the plain and (despite receiving none of the promised gifts) drive off the enemy.

The parallel with Achilles’ situation at Troy is clear. Even the name of Meleager’s wife Cleopatra (‘ancestral fame’) is a variant of that of Achilles’ companion Patroclus. But at Troy the power of myth fails to sway Achilles, whose refusal to fight becomes a legend in itself.

Postscript: Atalanta & the Golden Apples

As for Atalanta, some claimed that she sailed on the voyage of the Argo, others that she bore Meleager a son, but most agreed that, a virgin, she returned in triumph to her homeland of Arcadia. Although her father welcomed her, he was determined that she should marry without delay; Atalanta was equally determined she should not. They agreed on a compromise. All suitors must compete with Atalanta in a footrace. She would marry whoever managed to defeat her; any who lost, she would kill.

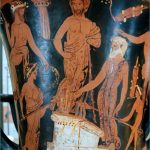

Meleager in the Iliad Photo Gallery

As Atalanta was the fastest runner alive, fresh burial mounds soon sprang up throughout Greece, until Aphrodite took pity on a local prince, Hippomenes. She gave him three golden apples and helped him trick his way to victory. The race began. Atalanta effortlessly eased ahead. But as she did, a golden apple, dazzling in the sunlight, landed with a thud before her feet. She stopped; she picked it up; she marvelled at its beauty; and when she resumed running Hippomenes was ahead. Then a second apple, and a third – and Atalanta watched bewitched as Hippomenes claimed victory. The two lived in chaste wedlock until one day desire overtook them at a sanctuary of Zeus, where they sacrilegiously consummated their love. So Zeus changed both into lions – mistakenly believing that lions couple only with leopards, and not each other.

Dionysus & the Spring of Callirhoe

A local Calydonian myth concerns the perils of love. Pausanias records how Coresus, a priest of Dionysus, fell in love with the beautiful Callirhoe. The more he wooed her, the more haughtily she rebuffed him So he prayed for help to Dionysus. Immediately, the Calydonians displayed symptoms of gross drunkenness, and many died deranged. At last the oracle at Dodona revealed that the sickness came from Dionysus and would end only if Coresus sacrificed to Dionysus either Callirhoe or a willing substitute. When no one would save her, Callirhoe ran to her parents, but even they refused to help her. Her only future lay in death. Preparations proceeded as the oracle instructed. With Coresus presiding, Callirhoe was led to the altar – but Coresus yielded not to anger but to love. He killed himself in her place – the loftiest example of true love in all history. Callirhoe, overcome by compassion for Coresus and shame for her treatment of him, cut her throat by the spring near Calydon’s harbour, which has been named in her memory ever since.’ Appropriately, Callirhoe’ means Fair Flowing’.