HELL GATE BRIDGE MAP

LONGEST STEEL ARCH SPAN 1916-1931

Crossing East River at Hell Gate, Queens-Bronx, New York

Designer/Engineer Gustav Lindenthal

Completed 1917

Span 977 feet (298 meters)

Material Steel Type Arch

Fittingly, the color of one of the world’s strongest bridges testifies to the power of pink.

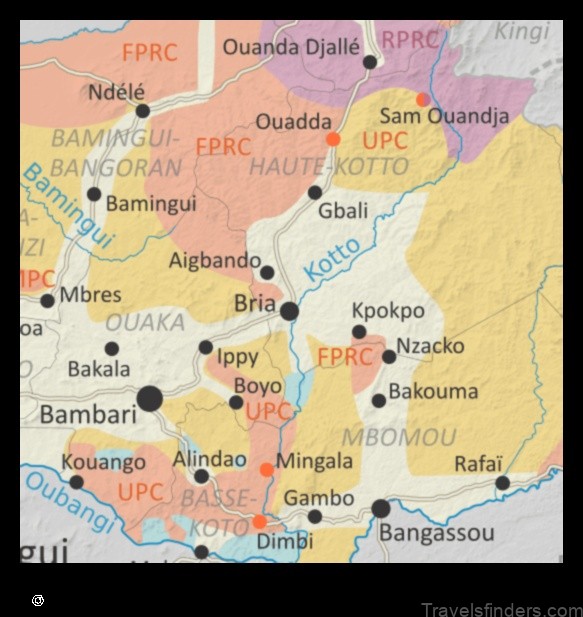

When it opened in 1917, the Hell Gate Bridge was a crucial rail link, finally connecting the Pennsylvania Railroad line (now Amtrak) to New England. Once the longest arch bridge in the world and the prototype for the far more famous Sydney Harbour Bridge, it was the last hurrah of the railway era. Today the least known of New York City’s major bridges, it attracts more notice for its paint color than for its ingenious, supremely strong structure. Self-taught engineer Gustav Lindenthal (1850-1935) was born in what is now the Czech Republic, and emigrated to the United States in 1874. By the time he was thirty, he had his own engineering practice in Pittsburgh. He was soon recognized for what Tom Buckley in a 1991 New Yorker article described as “the extraordinary intelligence, energy, and self-discipline that enabled him to teach himself mathematics, engineering theory, metallurgy, hydraulics, estimating, management, and everything else a successful bridge designer had to knownot to mention, in his case, English.” His ambition brought him to Manhattan. New York mayor Seth Low, a proponent of the City Beautiful movement, gave the newly formed Municipal Art Commission veto power over the designs of major public works. He appointed Lindenthal, who shared his aesthetic convictions, New York City bridge commissioner in 1902. Lindenthal would oversee the completion of three major East River crossings: the Williamsburg (1903), Manhattan (1909), and Queensboro (1909) bridges.

HELL GATE BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

The confrontation of rail and city posed one of the major technical and aesthetic puzzles of the Industrial Revolution . [The] Hell Gate Bridge symbolized the era with all its pretension, ambiguity, and power.

DAVID P. BILLINGTON, THE TOWER AND THE BRIDGE MAP, 1983

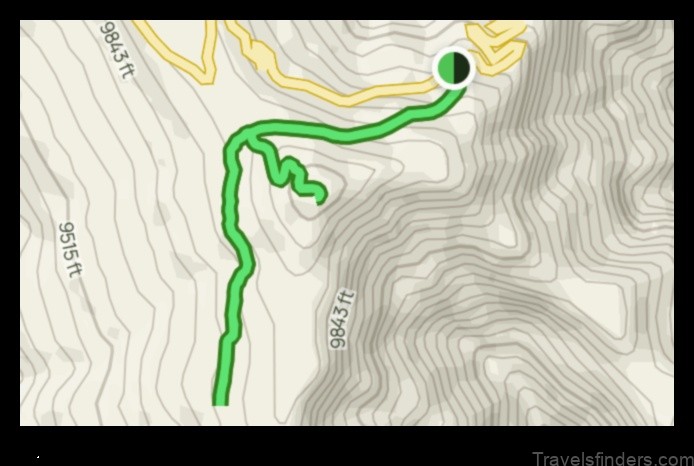

The Hell Gate Bridge is the chief element of a long and complex rail link, consisting of two additional bridges (the Little Hell Gate Bridge, an inverted bowstring truss with four 300-foot [91-meter] spans, and the Bronx Kill Bridge, a double-leaf bascule) and a series of viaducts and overpasses that stretch for 3.2 miles (5.1 kilometers) from Queens to the Bronx. Lindenthal considered two arch designs: the first, crescent-shaped, was inspired by Eiffel’s Garabit Viaduct (see here); the second was a flatter, spandrel arch. Preferring massive forms that looked strongand wereLindenthal went with the latter. To make the bridge appear even stronger, he increased the distance between the upper and lower chords of the arch and situated it between two massive, though structurally unnecessary, masonry towers. Critics have discussed the merits of the recurved arch and the towers at length. Not debated is the four-track bridge’s strength: its arch sustains a compressive force of 150,000 tons (136,077 tonnes), requiring the heaviest girders ever fabricated. Lindenthal is remembered for his bold, original designs; for the Hell Gate Bridge, which is his masterpiece; and for mentoring Othmar Ammann and David B. Steinman, who would eclipse him to become the most prominent bridge builders of the twentieth century. Lindenthal would die unfulfilled, having never built a bridge across the Hudson River, his all-consuming obsession since he first advanced the idea in 1885. That span, the George Washington Bridge (1931; see here), would be built by his former assistant Ammann.

The 100-foot (30-meter)-high viaduct piers were made of concrete instead of the crisscrossed steel girders first proposed because city officials feared that inmates of the Wards Island psychiatric hospital and Randall’s Island correctional institution would climb them and escape. Lindenthal, in the center, poses with his crew, including Ammann to his right, in front of the finished bridge.

Lindenthal’s first major bridge commission was the Smithfield Street Bridge (1881-89) in Pittsburgh. A lenticular, or lens-shaped, truss, the bridge was a harbinger of the diverse bridges that arose from Lindenthal’s ongoing exploration of steel structure.