The walls of The Firs are covered in Stern’s paintings – some of them among her best works. ‘Recently the hype about the extraordinary prices that have been achieved for her work has brought people into the museum, says director Christopher Peter. ‘It’s heightened their awareness of it; that kind of money just seems to excite people. It’s been quite useful I suppose. That awareness hasn’t happened before. the Firs, in Cecil Road, Rosebank – the home where the painter Irma Stern lived and worked for almost 40 years – houses the biggest collection of her work in South Africa, as well as her collection of rare African artefacts, some of which make frequent appearance in her still-life paintings.

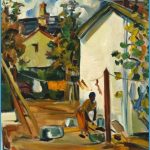

Although Stern was inspired by her journeys into Africa and elsewhere, it’s here that she returned to paint, to this richly exuberant home of hers, surrounded by carvings and artefacts, European furniture and sculpture and, outside, a large camellia, palm and strelitzia-filled garden. Her vivid yellow studio is as bold and as vigorous as her paintings, the finest of which demonstrate her grasp of the expressive use of colour.

‘I think her epic lifestyle and extraordinary presence have left a distinct stamp on the style of this house, and her personal taste adds to her mystique. But it’s an artist’s house and it’s filled with high-quality objects that she’d collected for their purity and integrity, says Christopher Peter, the museum’s director. ‘She responded to them in a visceral way; they inspired her work and are a part of her intellectual creativity. It’s not a flamboyant house. It’s not an antiquarian’s house either, or a feminine one. It’s an interested artist’s house. It has a sombre quality. It’s melancholic. It’s the home of a person driven to create as an emotional outlet.’

IRMA STERN MUSEUM Rosebank Cape Town Photo Gallery

Her dining room, perhaps the second most important room in the house, is crammed with carved and painted furniture, and with saints and religious icons with myriad provenances, ranging from 15th-century Spain to 19th-century English neo-Tudor. Painted oxblood red, it was the scene of lunches and dinners where Stern, described as resembling an officiating pope, presided over ebullient, colour coordinated settings and heaps of food.

‘Each course, writes Rebecca Hourwich Reyher, who came to lunch in October 1924, ‘was served on a tier of dishes and doilies: first there was bouillon; then cauliflower from a head that almost covered a turkey sized platter, and asparagus… After a mountain of vegetables had been consumed, the waitress brought forth a platter of roast beef, a twin platter of roast chicken, a heap of Yorkshire pudding, some peas, potatoes and cabbage, plus a tomato and lettuce and mayonnaise salad. This light repast was topped by chocolate pudding, canned peaches, & whipped cream and a pink and tan candy encrusted macaroon layer cake.’

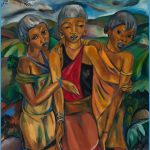

Controversial in her lifetime, and larger than life, Stern’s stylistic innovations disrupted the reserve of a cautious, conservative provincial public. But, by the time she died, her career as a Modernist painter, and her contribution to South African Modernism, marked her as one of South Africa’s most important artists. And her popularity as a collectable artist has skyrocketed in recent years. At auction, records for the sale of her works have been broken time and again, with the last recorded price at auction being R21-million for Two Arabs still in its original Zanzibar frame. Stern’s Zanzibari works are among her most sought-after. ‘They represent aspects of the painter at the heights of her creative powers, said Professor Neville Dubow, a former director of the museum, at the 1982 opening of her exhibition, ‘Irma Stern in Zanzibar 1939-1945’.

Vivid yellow, Stern’s studio survives, as bold and as vigorous as her paintings, the finest of which demonstrate her grasp of the expressive use of colour.

The death dance is a well-known subject in Western art. A variation on the theme can be seen in the four panels of a cupboard in Stern’s studio, which she painted early on in her life.

Looking from the dining room towards the curator’s office.

Portrait of Dr Louis Herrman, 1922. Herrman was the principal of Cape Town High School and a writer and leading Cape Town intellectual. This painting is a study of a man’s character as suggested by his appearance.

The dining room is filled with antique furniture, both painted and carved, and with a variety of European religious icons. This was the hub of Stern’s home, where she entertained and held court.