The Milky Way represented both a practical means of navigation but more significantly a celestial path – a path that the soul had to follow in order to enter the spiritual realm. (In other beliefs it was also the path a soul took to incarnate into physical form and thereby become earth bound). This Other World later became associated with the Christian concept of Heaven. The Milky Way thus became a metaphor for the Camino de Santiago. It was, after all, the way the saint himself would have navigated to this part of the world and the way that medieval pilgrims followed in order to find his tomb. So the Milky Way was the Way of the Stars’ which in turn came to mean The Way of St. James’.

Indeed the sun and moon and all the planets appeared to follow this self same path on their respective journeys across the sky. A celestial or heavenly reflection of the earthly path – the way of the Stars – follows the mystic expression as above so below’. It is likewise used in the symbology of many aspects of the Western Mystery Tradition. The Knights Templar were one such esoteric order who sought to preserve the Perennial Wisdom and to promote its dissemi nation to those who earnestly sought to find it. In our outwardly driven society we of course interpreted the Knights activities as protecting only the physical safety of the pilgrims. However, the safeguarding of the inner way was also a motivating force for the many within the Order.

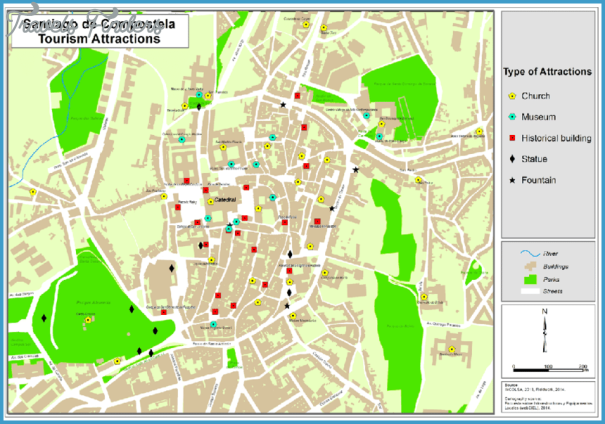

Santiago de Compostela Attractions Map Photo Gallery

While evidence exists to support the contention that the Knights Templar had sailed to the Americas around the time of the Spanish Inquisition, a hundred years before Columbus, it was undoubtedly Columbus and his expedition forces that popularised the discovery’. Up until that time pilgrims had journeyed to the end of the earth to witness the sun rising above Monte Pindo and sinking below the western horizon. It was to be another 100 years before Copernicus stated that the sun was in fact the centre of the universe and so the earth merely rotated itself away from the sun and into darkness. A fact that, from our continuing anthropocentric view, we still don’t generally experience. It appears that the mists and myths that surrounded Finisterre at the dawn of history are as alive and relevant today as we enter this new millennium.

FURTHER READING in English is limited. Much of the information given here comes from local information garnered along the way itself. Myth and legend abound and, while frequently based on some historical occurrence, the, are – by their very nature – not dependent on fact. 1 was lucky enough to find, in my local library, several out of print editions of blogs that referred to the impor tance of Finisterre as a place of spiritual transformation. You might likewise Ir your own library or search the web under Finisterre / Celtic mythology etc.

The Practical Path: The Asociacion Galega de Amigos do Camino de Santiago and other friends of the way have recently opened up a truly delightful path to Muxfa that follows the coastline northwards along earthen tracks and forest paths. Over half of this stage is on such natural pathways. The remaining 45% is along quiet country roads with less than 1 kilometre on the main C-552 out of Finisterre.

The village of Lires (13.2 km from Finisterre) makes a convenient half way stop. It has accommodation and a pleasant modern bar where you can get bocadillos (no hot meal). Just beyond Lires you need to ford the wide rio do Castro (stepping stones). If the river is in flood you may need to take a detour lo A Pontenova 4 km upriver from Lires. If there has been a lot of recent rain then add an extra 2 hours to your journey time for this eventuality). Apart from Lires there are no other facilities for food or drink (excepting the handsome Hoiel Dugium in Salvador just outside Finisterre). As accommodation in Muxia is limited you may wish to blog ahead during the summer season (see Muxfa for details).