After this treasure of the Ottoman Empire was destroyed, an international team rebuilt it.

Following the disastrous losses of art and architectural treasures in Europe during World War II, the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was signed at The Hague in 1954. The first treaty to acknowledge cultural heritage as a basic human right worthy of respect and protection, it has been repeatedly ratified, most recently in 2016. Sadly, the treaty did not save the Stari Most, the four-hundred-year-old crossing that had given the city of Mostar its life, name, and prominence, but it did help resurrect it.

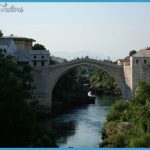

Mostar, a historic city in Bosnia and Herzegovina, straddles both banks of the Neretva River. It was named for the bridge at its heart, the Stari (short for Stari Most or “Old Bridge”), as locals called it. A masterpiece of Ottoman engineering, the humped arch bridge was designed in the sixteenth century by master builder Mimar Hayruddin for Sultan Suleyman, called “the Magnificent.” Centuries of commerce over the bridge had polished its limestone treads smooth they had always been concerning themselves with the bridge; they had cleaned it, embellished it, repaired it down to its foundations, taken the water supply across it, lit it with electricity and then one day blown it all into the skies as if it had been some stone in a mountain quarry and not a thing of beauty and value, a bequest.

STARI MOSTAR BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

IVO ANDRIC, THE BRIDGE MAP ON THE DRINA, 1959

Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike gathered at this bridge, and at earlier crossings at the site. Despite conflicts in the region throughout its history, Mostar’s mosques, synagogues, and churchesall located within close proximitystood for centuries as a visible sign of the intermingled lives of its various communities.

The brutal war of 1993 between Serbs and Muslims literally ripped the city of Mostar in two: the Old Bridge was destroyed. In the name of “ethnic cleansing,” hundreds of irreplaceable architectural treasures in the Balkans were torched, dynamited, and bulldozedan attempt, it seems, to eradicate a culture by destroying the very places where the people had gathered to live their lives. The Old Bridge was deliberately targeted for its symbolic significance. It collapsed and sank into the river on November 9, 1993, after almost twenty-four hours of artillery fire. Although a temporary metal bridge was erected, the absence of the Stari Most epitomized the horrors of the war.

Calls for its reconstruction began in early 1994. An international partnership led by the World Bank, UNESCO, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and the World Monuments Fund, and funded by several countries, including Italy, the Netherlands, and Croatia, led the rebuilding effort. Engineer Rusmir Cisic and architect Tihomir Rozic, both natives of Mostar, directed a team of international and local experts in Ottoman architecture and bridge restoration.

UNESCO signed Mostar and its environs into the World Heritage List in 2005, recognizing both the bridge’s symbolic power and the structural and historical authenticity of its replacement.

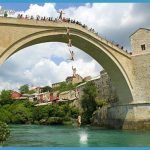

Meticulous preliminary investigationsinto the site’s geology, past surveys and photographs, and centuries-old methods of stone arch constructionthemselves were a remarkable contribution to knowledge of Ottoman architecture. Rebuilding began in 2001. Tenelia, a fine-grained limestone, was extracted from the same quarry as the original stones; only a few of the original stones were used, as most were too damaged. A wide celebration greeted the restored bridge’s opening on July 23, 2004.

Deceptively simple and unadorned, the new bridge, like the old one, derives its beauty from the harmonious connections it makes between the city and the river beneath it. But its restoration points to something more. The protection of structures and the cultural memory they embody, once more symbolized by a bridge in Mostar, is a shared task, one that uplifts us all.

Once again, divers thrill tourists with “angel jumps,” leaping from the bridge 66 feet (20 meters) down into the water below.

“The mere use of one’s eyes in Venice is happiness enough.”