Balaklava, Ukraine

Balaclava thousand miles to the south of Dubna lies the Crimean village of Balaklava.

Although today it might be more associated with crime than with Crimea, the balaclava helmet – a warm, usually woollen, item of headgear that covers most of the head, neck and face – famously takes its name from the strategically significant port of Balaklava on Ukraine’s Black Sea coast. The garment itself has a long history: it originated in the thick, low hoods of cloaks worn as far back as the Middle Ages, which eventually became detachable and morphed into entirely separate items of headgear originally known as ‘Templar’ or ‘uhlan’ caps.

But if the balaclava as we know it already had a name, why rename it after a town in southern Ukraine? Well, to answer that we need to travel back to 25 October 1854, and one of the most infamous days in British military history.

Where is Balaklava, Ukraine? – Balaklava, Ukraine Map – Balaklava, Ukraine Map Download Free Photo Gallery

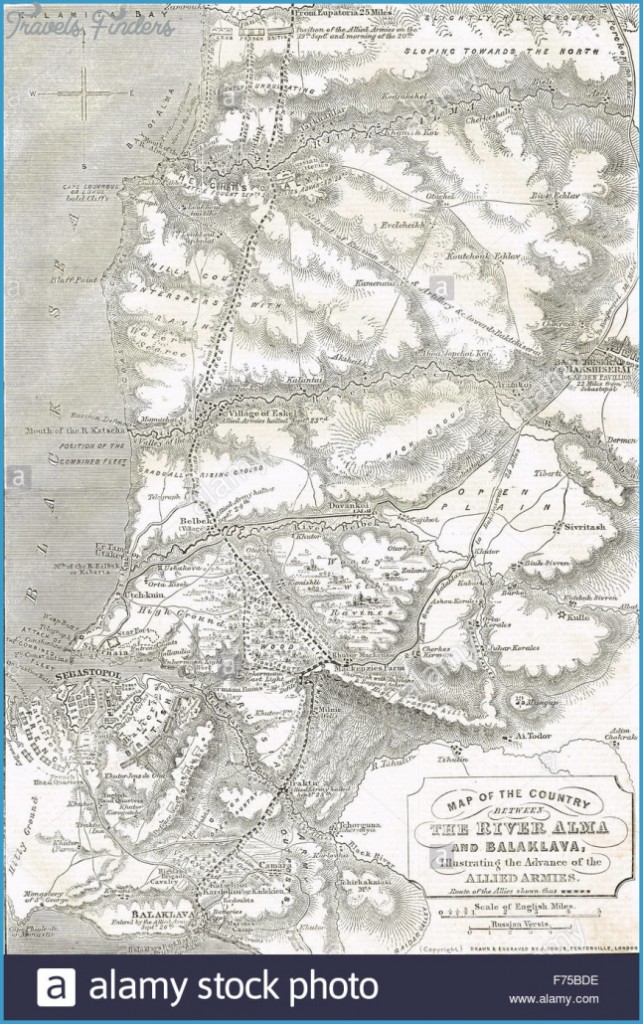

By the winter of 1854, the Crimean War had already been raging for a year, and it would be another year and a half before the Treaty of Paris would bring hostilities to an end. Twelve months into the conflict came the Battle of Balaklava. An alliance of British, French and Ottoman troops clashed with the Russian empire, which was trying to take control of the port and thereby disrupt the allies’ supply chain.

In the end, the allies successfully defended the port but lost control of one of their most important supply routes, which was ferrying much-needed food and equipment to the nearby besieged city of Sevastopol. The battle was therefore indecisive, but its impact would nevertheless be momentous.

By 9.30 on the morning of 25 October, the allies had already secured two significant victories. Under the command of Sir Colin Campbell, an infantry unit of the 93rd Highlanders had seen off two terrifying Russian cavalry charges, while Sir James Scarlett’s Heavy Brigade – no more than three hundred cavalrymen – had routed some two thousand Russian troops in an extraordinary show of force that had taken just ten minutes. The allies ultimately seemed to be in the ascendancy, but as the Russian cavalry retreated over the hilltops and the Heavy Brigade began to celebrate victory, word reached the secondary Light Brigade that Lord Raglan, in overall command of the British forces, now wanted them to advance rapidly into the fray.

The order seemed absurd: in the aftermath of a victory that had already been secured, Raglan was apparently telling the Light Brigade to charge forward into a blind valley surrounded on three sides by scores of Russian troops. But the Brigade, under the command of Lord Cardigan, knew it had to obey no matter how suicidal the order seemed. As Alfred, Lord Tennyson would later put it, ‘Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die.’

By the time the Charge of the Light Brigade was over – barely twenty minutes later – one sixth of the six hundred or more men who had entered the north valley of Balaklava had been killed. Nearly as many again had been injured or captured, and almost four hundred horses had been lost.

It later transpired that Lord Raglan’s order had actually been for the Light Brigade merely to advance after the retreating Russian troops, to prevent them from capturing British guns that had been positioned in the surrounding hills. But as the order had been passed from messenger to messenger, it had become corrupted and truncated, so that by the time it reached Lord Cardigan, all that the Light Brigade was told to do was ‘advance rapidly’ back into the battle.

The blunder cost the allies dearly, and when news broke of the bloody Charge of the Light Brigade, it soon gained a reputation as one of the British Army’s most disastrous missteps. Admittedly, some later historians have been more forgiving, suggesting that the insane bravery demonstrated by the British in charging into near certain death unnerved the Russian side. But there’s little argument that this was an ignominious end to what could otherwise have been a decisive Allied victory.

That ignominy, however, had a curious linguistic consequence, as the battle left a lasting impression not just on English history, but on the English language. And we’re not just talking about balaclava helmets.

According to reports, Lord Cardigan (like most British officers at the time) happened to be wearing a distinctive short, light, close-fitting woollen waistcoat on the day of the battle; the cardigan ultimately came to be named in his honour. Lord Raglan, meanwhile, was wearing a thick overcoat with noticeably wide, loose sleeves; it likewise came to be known as a raglan jacket. Sir Colin Campbell’s red-coated Scottish troops had succeeded in seeing off those two early Russian cavalry charges by forming one long narrow line of men, standing two abreast; war reporters referred to it as a ‘thin red line’, a phrase that eventually became synonymous with any meagre yet fiercely effective defence. And, of course, the thick woollen helmets that the British troops had taken to wearing to protect themselves

from the brutal weather of the Crimean mountains came to be known by the name of the battle at which they had been worn.

Curiously, the earliest written evidence we have of one of these helmets being called a balaclava dates from 1881, some twenty-five years after the Crimean War was over. Perhaps the fact that the battle’s name had remained current until then is testimony to how significant, and infamous, the event had been.

Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1854) is one of his most popular and famous poems. Less well known is the poem he wrote nearly twenty years after the Crimean War celebrating the more successful ‘Charge of the Heavy Brigade’ (1882) that had taken place earlier that morning:

The charge of the gallant three hundred, the Heavy Brigade!

Down the hill, down the hill, thousands of Russians,

Thousands of horsemen, drew to the valley – and stay’d

Lord Raglan had lost an arm at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and preferred this distinctive type of jacket as it disguised his missing limb: the sleeve fabric was looser and extended all the way to the neckline rather than stopping at the shoulder, a style that is now known as a raglan sleeve.