Another of my jobs at Hullavington was to devise methods for teaching ‘nought feet navigation to pilots intruding into enemy territory when they would be unable to take their eye off the ground ahead, and must be jinking all the time to avoid anti-aircraft fire. It amounted to map reading without maps, in other words all the map reading had to be done on the ground before taking off. It sounds an impossible requirement but, with the right methods, and plenty of drill, pilots could find a haystack 50 miles off while dodging about all the way to it. Oddie reasoned that it was impossible for me to do this sort of work if I was not allowed to fly or, for that matter, navigate. As a result, I was not only navigating continuously in the various types of aircraft at the station, but also had a light plane for solo flying and experimental work whenever I wanted it. This enabled me to prepare the flight tracks for the instructional films we were making, work up interesting exercises, and also to fly myself home occasionally at the weekend.

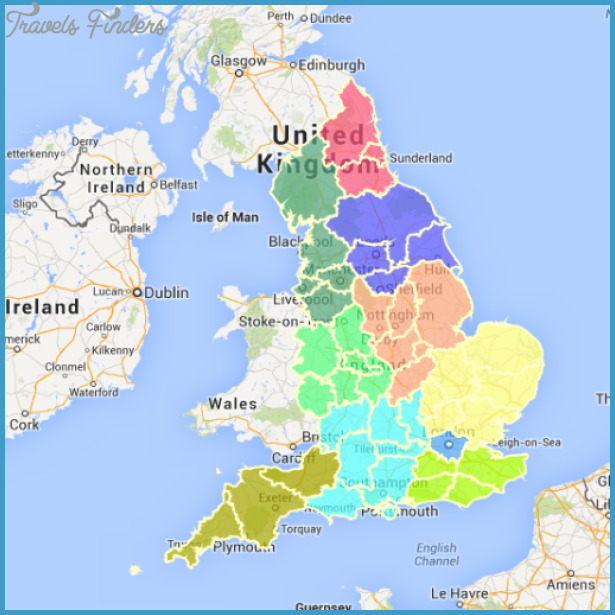

England Map With Counties Photo Gallery

I used to land at Fairlop, a mile from our house at Chigwell Row. One morning, just before I took off, a cryptic message came through from Air Traffic Control London saying that I must take great care while flying and look out for anything strange. I usually flew low, because it was more interesting, and I was surprised to see all the children dash across a playground and take cover as I flew over. When this happened a second time, I realised that they were taking cover from me, and when it happened a third time, I wondered what it was all about. On this occasion I landed at the Fighter Station at Hornchurch. As I stepped out of the plane, I saw one of our fighters tip a doodlebug over with its wing tip, and send it crashing into the ground where it exploded with a mighty bang. The schools had mistaken my little monoplane for a doodlebug. When I got home I found that one of the first three of these infernal machines had flown low over our house where Sheila was living alone. Our house was slightly damaged many times, and naturally it was a great worry to me leaving Sheila there. I tried to persuade her to come down to Wiltshire, but the only accommodation I could find was a room in a house which she would have to share with several others. She said that she preferred living in her own house with the bombs. One day I returned to find that a doodlebug had exploded nearby, and blown every leaf off the big lime tree next door. The completely bare tree looked strange in the middle of summer. Some weeks later I came home and was delighted to see a new crop of leaves appearing on the tree, just as if it was at the beginning of spring.

I tried to console Sheila by telling her that the bomb risk in London was nothing like the risk from flying accidents at the ECFS Most of our students had been doing administrative office jobs before coming on the course, and when they were expected to fly every one of our thirty-seven different types of aircraft while undergoing an intensive course of lectures, it was not surprising that we had a high casualty rate. The chief safety factor when flying is thorough drill in handling the aircraft. It was thought, however, that we could not win the war if we played for safety.

It is an ill wind that blows no good, and if any of my students were lost on a navigational exercise I used to spend many hours in my light aeroplane searching where I estimated them to be. Two South African majors were lost on one exercise, and I hunted for days among the Welsh hills. Three months later when we had given up all hope for them, word came through that they were prisoners of war. They had flown the reciprocal heading of their compass, south-east instead of north-west. When they crossed the English Channel they thought it was the Bristol Channel. They were grateful when an airfield put up a cone of searchlights for them, and it was not until they had finished their landing run on the airstrip and a German soldier poked a tommy gun into the cockpit that they realised that they were not on an English airfield.

I often used to make solo flights to operational stations to find out if there were any developments in navigation and, I must admit, to try for a job as navigator on a raid. When I climbed to the control tower after landing on a strange airfield the duty officer would look at my wingless tunic and say, ‘Where’s the pilot? I enjoyed this, and regarded it as some consolation for the indignity and disregard the non-flying man had to put up with from operational pilots.