For the first three days, the weather was rough with gales. Heavy seas burst on the deck, and I reckoned that it took thirty seconds after a sea had broken on deck before the water finished running out of the lee scuppers. I had considered Gipsy Moth a dry boat apart from one or two minor leaks, and I had pumped no water out of her during the three months she had been afloat. After the first three days, however, all the cabin walls were streaked as if they had been in a slanting shower of rain, and everything was damp or wet: I can only imagine that the tremendous weight of seas bursting on deck opened the planking or seams for an instant to shoot spray through.

The terrific crash of a sea several times started me out of my berth, thinking that the yacht had been struck by a steamer, or that the mast had snapped. While I was asleep one sea shot me into the air off the heavy wooden settee I was sleeping on and jumped it out of its fitting. The clothes I got wet stayed wet, and I did not get a chance to dry them out until thirty-seven days later. At the end of the first three days I had had nothing to eat except a few biscuits; I had been feeling seasick or queasy all the time. Reading through my log gives me an impatient longing to sail the race again. I see the mistakes I could have avoided, and how I could have made a faster pace. This is nonsense really, for the mistakes and errors are the price for the great romance of doing something for the first time.

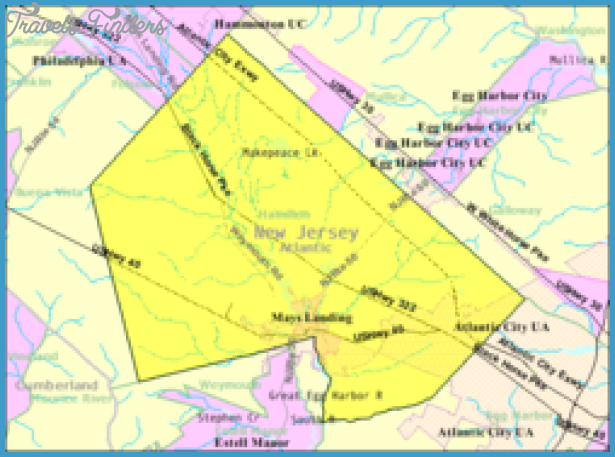

Atlantic Map With Counties Photo Gallery

Miranda’s antics cost me a lot of time. The lever which locked the wind vane to the tiller was periodically knocked free by the backstay, and I would be rousted out of my bunk to find the yacht headed the wrong way. I had a nightmare fear of the yacht’s jibbing herself to bring the wind vane against the backstay and snap its spars. Immediately I sensed the yacht’s going off course – I soon became sensitive to the least change in sailing conditions – I rushed out to the stern, whatever I was doing, or however undressed.

Reefing the mainsail, lowering it, and hoisting the trysail in its place, with the frequent changing and handling of heavy Terylene foresails, exhausted me, and I was not sailing the yacht as she should be sailed. I envied my rivals the comparative ease with which they would be able to change the smaller sails of their boats, although I reckoned that their boats were too small, just as mine was too big; the best size for this race would be, I thought, a nine-tonner. In rough water my bigger boat should be better off, but I was losing too much valuable time over my sail changing. It took me up to one and a half hours to hoist the mainsail and to reef it in rough water. I know it sounds inefficient, but my 18-foot main boom was a brute to handle when reefing. I had to balance on the counter and slacken off the main sheet to the boom with one hand, while I hauled on the topping lift with the other hand to raise the boom. Meanwhile, it would be swinging to and fro, and I had to avoid being knocked out by it.

While hoisting the mainsail, I could not head into wind for fear of the yacht’s tacking herself, and causing further chaos. As a result, the slides would jam in the track, the sail would foul the lee runner, and the battens would hook up behind the shroud as I tried to hoist the sail. All this time the boat would be rolling to drive one mad, and bucking. With heavy rain falling, and wave crests sluicing me, I would feel desperate until I got into the right mood, and told myself, ‘Don’t hurry! Take your time! You are bound to get it done in the end. Once, after all this, I had just got the mainsail to the top of the mast when the flogging of the leech started one of the battens out of its pocket. So I had hurriedly to lower the sail and, after saving the batten, go through the whole procedure again.