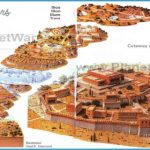

Troy enjoyed a commanding position. Although today alluvial deposits from the River Karamenderes Qayi mean the coastline has moved almost 6 km away, in the early Bronze Age Troy was by the sea. Sited near a wide, shallow bay just south of the entrance to the Dardanelles, it controlled the shipping lane between the Aegean and the Black Sea. Moreover, brisk westerly winds meant that sailing ships could voyage east along the Dardanelles only by rowing, but even this was difficult. The west-flowing current runs at up to 3 knots, so to maintain headway oarsmen needed to achieve a constant speed of at least 5 knots. Where better to rest and wait out the winds than in the bay at Troy? The city enjoyed great prosperity. Archaeologists have identified nine phases of development, some of which are subdivided for greater precision.

In the early third millennium bc Troy I was a village of stone and mudbrick houses, but already by its second phase around 2550 to 2300 bc, stone-crowned ramparts pierced by monumental gates surrounded a citadel with large buildings, used for public gatherings or religious purposes. A further palisade enclosed a lower town covering 9 ha. Troy II was destroyed by fire, perhaps in war, for its people did not salvage their riches, which included artifacts made from gold, silver, bronze, electrum, carnelian and lapis lazuli. When Heinrich Schliemann discovered Troy II’s exquisite items of jewelry, he identified them as the ‘Jewels of Helen’. They were a thousand years too early.

Excavating between 1871 and 1879, Schliemann wrongly identified Troy II as ‘Homer’s Troy’, digging out much of what lay above and badly damaging three phases of Troy’s history. This compounded destruction wrought by Hellenistic Greeks, who flattened the mound for the foundations of their Temple of Athene.

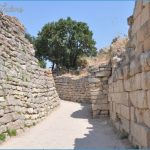

Enough survives to tell that the citadel of Troy VI, founded around 1700 bc, was magnificent. Limestone walls, 5 m wide, angled gently inwards as they rose, their line softened by subtle vertical offsets. Fine towers soared high. A paved and well-drained road led through the city, where on terraces two-storeyed buildings stood, many with defensive ground-floor walls and pillared halls. Outside the citadel was a thriving town, covering 30 ha, protected by a ditch and palisade and provided with water by a sophisticated system of artificial shafts and tunnels. Finds suggest that Troy VI traded with the Greek world rather than Anatolian Hittites, but around 1300 bc this changed perhaps exacerbated by Troy VI’s partial destruction, by earthquake or plunder. The discovery of one arrowhead has excited more speculation than it perhaps deserves.

Troy in History & Today Photo Gallery

In the citadel smaller houses now crowded once open spaces. New towers were added, and the Lower Town expanded. We know this bustling metropolis prosaically as Troy VIIa, but the Hittites called it Wilusa. Thirteenth-century bc Hittite correspondence reveals that an attack on Wilusa by south Anatolian Arzawans prompted its king Alaksandu to bring his city under Hittite rule. Another mid-thirteenth century Hittite document is written to the king of the Ahhiyawa – probably the Hittite form of ‘Akhaioi’, as Homer calls the Greeks – confirming ‘an agreement regarding Wilusa, over which we went to war’. Around 1200 bc the Hittites intervened once more when the Wilusan king Walmu was ousted from his throne. Then around 1180 bc Troy VIIa was destroyed by fire.

While these fragmentary references suggest tensions and even warfare, neither they nor archaeology confirm the historicity of the Trojan War. It is not surprising. Mythology and epic are not history. Both rely on invention and exaggeration, and disappointment that Troy was not the scene of a ten-year war over Helen must be tempered by reflecting on its influence on our imagination and creativity over three millennia. Inspired by a brief war over Wilusa which ended in a treaty between Greeks and Hittites, poetic vision fused with reality to form a masterpiece.

The quickly rebuilt Troy VIIb shows signs of cultural continuum, but subsequent building techniques and ceramics suggest a new, immigrant population. Unlike mainland Mycenae or Tiryns, Troy was inhabited throughout antiquity. With the receding shoreline, ships waiting to enter the Dardanelles abandoned Troy to shelter in the lee of Tenedos, but as the city’s commercial star waned its cultural importance grew.

In 480 bc, Persia’s Great King Xerxes sacrificed a thousand cattle at Troy’s Temple of Athene before launching his unsuccessful invasion of Greece. In 334 BC Alexander the Great, who kept a copy of the Iliad under his pillow, landed at Troy, where he too sacrificed before invading Persia, and ran naked to Achilles grave mound. When Athene’s priests presented him with ancient armour claimed to date back to the Trojan Wars, and offered to show him the lyre belonging to his namesake, he replied that he preferred to see the lyre to which Achilles sang the famous deeds of men.

Alexander planned to build the largest temple in the world to Athene at Troy, but it was never begun. Nonetheless, his successors enhanced and enlarged the city, restoring the existing Temple of Athene with sculptures mirroring those of the Parthenon in Athens. A theatre was constructed and festivals inaugurated. Troy prospered, assuming renewed significance under Julius Caesar, his adopted son Augustus and subsequent Roman emperors. As Caesar’s family, the Iulii, traced their descent through Iulus to Aeneas and Anchises, so the ruling Romans lavished money on the city they perceived as their ancestral home.

Constantine considered making Troy his capital before settling instead for Constantinople. Under the Byzantines, Troy’s importance diminished, and in ad 1452 their nemesis, Mehmet the Conqueror, paid one last visit to the site to mark his victory over the crusading infidels, now couched as the successors to Homer’s Greeks.

For 400 years the site lay almost forgotten, but in 1865 a British expatriate, Frank Calvert, believing reports that Hisarlik was Homer’s Troy, bought the land and began digging. Six years later a chance conversation in nearby Qannakale so enthused the romantic German Heinrich Schliemann that he took over, ploughing much of his wealth into unwittingly destroying valuable archaeology. Excavations have continued ever since.