Despite being the setting of a well-known myth, little is known of Calydon until the time of its abandonment. Signs of occupation from the eleventh century bc suggest that it grew up round the

archaic sanctuary of Artemis Laphria, an important religious centre. Briefly fought over in the early fourth century bc, in the Classical and Hellenistic periods its two temples – one of Artemis (housing a gold-and-ivory statue), the other of Apollo – were augmented by treasuries and stoas. In the third century bc, Calydon and its newly fortified acropolis were enclosed by walls, 4 km (2^ miles) in circumference. The following century a lavish shrine to a local hero, Leon, was erected, with a colonnaded courtyard and a chapel, whose vaulted crypt contained two finely carved stone beds.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Actium (31 bc), which took place not far to the north, Octavian (soon to be called Augustus) forced the Calydonians to move to nearby Nicopolis, built to celebrate his victory over Antony and Cleopatra. Calydon, which Strabo called an ornament of Greece’, became a ghost town. Even its gods were relocated, their statues shipped south across the gulf to Patras, where their priests continued to observe ancient rituals. Here Pausanias witnessed the two-day festival of Artemis Laphria. On the first day, a young priestess rode in a chariot drawn by four deer to an altar, piled high with dried logs.

Calydon in History & Today Photo Gallery

Community and individuals alike take great pride in the ceremony. They hurl on to the altar living game birds and other animals (boars, deer, gazelles – some young, some fully grown).

They stack fruits from their orchards on to the altar, too. Then they set fire to the wood. When they did this, I saw creatures including a bear trying to escape as the flames caught, but the people who first cast them into the fire forced them back again. There is no record of anyone being harmed by these animals.

Meanwhile, the Calydonian boar hunt was a popular subject for artists, inspiring a wealth of sculptures, vase paintings and mosaics. The sixth-century bc Francois Vase (now in Florence’s National Archaeological Museum) shows Atalanta wielding a spear in the thick of the hunt, while on a second-century ad Roman mosaic in Patras Museum a stocky Atalanta draws her bow as dogs attack the boar.

In the second century ad, relics of the boar could still be seen. One intact tusk, three feet long, was housed in the Sanctuary of Dionysus in the Emperor’s Gardens in Rome, the other at the Temple of Athene Alea in Tegea. When Pausanias visited, the priests told him that, although in their possession, this tusk was sadly broken. But they did show him the boar’s hide, which he records was desiccated and without one bristle left’.

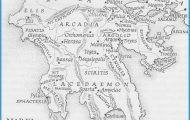

Calydon

Calydon, at first sight unprepossessing, is located by the busy motorway linking Antirrhio and Messolonghi. Near the car park is the theatre, with foundations of stage buildings and a rectangular orkhestra and auditorium. From here a path leads to the fenced hero-shrine – the site attendant will unlock the gate and show the subterranean tomb with beautifully carved stone beds, complete with pillows and other delicate sculptural details. Further on are the foundations of a temple, identified as the Temple of Dionysus, from where a track (right) soon leads to the Laphrion, with foundations of the temples of Artemis and Apollo. From the Temple of Dionysus another track leads to Calydon’s acropolis, surrounding which traces of city walls are visible. At the time of writing, the site had no signage and the guideblog was available only in Greek. There is no museum.