Collecting the musical past It is often pointed out that, unlike a painting, the object that serves to perpetuate a piece of music is not itself a work of art. It is simply a series of instructions for producing one. So the collecting of composers manuscripts has never been a preoccupation among the rich and the connoisseurs in the way that collecting pictures has been. People have collected music in order to perform it, not to look at it. Accordingly, music collections and libraries initially developed as necessary adjuncts to performing institutions, mostly in ecclesiastical and princely establishments. Other objects associated with composers have not been valued or collected at all until relatively modern times.

Once the age had dawned when composers came to be highly regarded, however, collectors showed increasing interest in their manuscripts. Many extensive collections were built up during the late 18th century and over the 19th. Most substantial music collections have by now found their way into national, regional, academic or ecclesiastical libraries, some bequeathed or sold by their owners, but some have been sold off at auction after their owner’s death and dispersed. Many private music collections still exist, but their number diminished greatly during the 20th century, and the process continues.

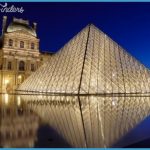

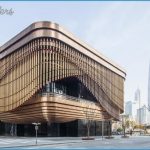

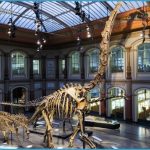

BEST MUSEUMS IN THE WORLD Photo Gallery

Interest in composers personal possessions and objects associated with them developed more slowly. Very few such artefacts survive even from the early 18th century. Seen as worthless at the time of the composer’s or his widow’s death, they were simply destroyed or, if of residual use, dispersed. Now, however, objects such as those itemized on p.4 are valued by collectors, especially documents, likenesses of all sorts and personal items, including, for example, locks of hair, writing implements and reading glasses, cigarette holders, pipes and walking-sticks, and of course the actual musical instruments that composers played. All such objects acquire a special aura through their proximity to the composer, and are invaluable to museums where any attempt is made towards a re-creation of his world. Much more survives from the 19th and 20th centuries than from earlier periods, partly because less time has elapsed but mainly because of the increasing importance ascribed to the wider legacy of composers. The precedents established in museums commemorating writers and artists have encouraged the families and friends of composers to retain and preserve as much as possible.

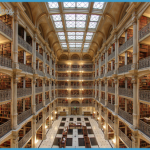

Echoing the traditional formula used in musical biographies, many composer museums relate their subject’s life story on illustrated display boards on the walls, with glass cases below them in which relevant objects together with manuscript and printed music from the relevant time are displayed. If the museum is in a house in which the composer lived, space is allocated to his life and times, with special attention to the works written there and his connections with the area. Birthplaces usually tell the whole life story: the family background, with detailed chronological surveys of the composer’s life and works. Places of death more often summarize the life and then focus on the final years and the late works, tributes to the composer, his musical legacy and its posthumous reception. These sites are of particular interest where the composer is relatively little known outside the region. Displays concentrating on the period the composer spent in the house or the area may, however, be of even greater interest: with these a museum can contribute what are often entirely new perspectives to our appreciation of the music he wrote there. The best displays are usually the result of a successful collaboration between curators and scholars, and most depend to some degree on loans and reproductions from libraries, archives and private collections. They are further supported by images of key events in the composer’s life and the places where he lived and worked, usually shown as they were in his own day through prints or old photographs. The presence of art in musical museums encourages us to forge visual associations with sound.

Images of the composer and his times

Images of the composer ‘at home enhance the relevance and credibility of houses and rooms, as both composing and performing venues, and provide evidence of the composer’s world and his place in it. Many composer museums display unparalleled collections of graphic and plastic art. Some images on display may be by famous contemporaries, artists who were personal friends and occasionally collaborators on projects such as the sets and costumes for opera productions. But the art in composer museums is rarely in itself of very high quality. Not many of the greatest artists painted composers and their friends. The art is there and it is valuable because it shows us the composer, not – like a picture in an art gallery – because of its inherent beauty or artistic worth.

Inevitably, images of the composer himself generally constitute the central element, and the largest, in these collections of art. Among the best served are Liszt in Bayreuth and Rossini in Pesaro. The Mozart, Beethoven and Schumann birthplaces have rich collections. The most important portraits are those from life – drawings, watercolours and oils, reliefs, busts and statues, plaster casts of hands and life masks – and also death masks. They may illuminate unexpected corners, personal, social and historical. The succession of Dussek portraits at Caslav, for example, shows his startling personal inflation over the years. Kupelwieser’s watercolours capture the exuberance of Schubert and his friends during their summer idylls at Atzenbrugg, much as does the 1894 Bayros group portrait of the Strauss-Abenden in the composer’s flat in the Vienna Praterstrabe. Exhibitions at Bad Kostritz of the ‘Weltbild’, focussing on the achievements of distinguished contemporaries of Schutz, cast fresh light on his creative context.

The power and value of the evidence of portraits, many of them directly connected with a particular time and the place in which they now hang, is Rights were not granted to include these illustrations in electronic media. Please refer to print publication difficult to overstate. The well-known formal portraits of the four Mozart family members in the Salzburg Geburtshaus date from the 1760s, when the family still lived in Getreidegasse, just as the later Della Croce group portrait on display at the Wohnhaus across the river reflects their changed situation in the 1770s and 80s. Uniquely among composer memorials, the museum in the reconstructed house where Liszt died in Bayreuth celebrates his life through portraits, masks and sculpture. Chronologically arranged and supported by excerpts from his correspondence, they provide a personal context for his music; recorded examples are transmitted through speakers embedded in the walls. Puccini’s last portrait, completed just a month before his death, hangs in the Torre del Lago villa; although ravaged by his terminal illness, he is portrayed with great dignity. The transition from life to death is underlined by the presence of the composer’s remains in the chapel a few steps away. Schoenberg’s expressionist self-portraits in the Vienna museum challenge the viewer to suspend time and space to meet his gaze.

Other likenesses faithfully reproduce or take inspiration from a few surviving portraits held in diverse collections, many of them private; still others are posthumous portrayals, sometimes imaginative, sometimes interpretative. Caricatures may often be revealing, cruelly or benevolently, of quirks otherwise unrecorded. For composers who flourished after the mid-19th century, there are often rich photographic resources. Nowhere but in a few specialist books devoted to the iconography of a handful of individual composers and the occasional significant anniversary exhibition – such as those mounted by the National Portrait Gallery in London for the tercentenary of Handel’s birth or for the Mozart bicentenary by the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien – are the surviving images so systematically assembled for public view. Composer museums often own or borrow the originals of portraits we normally know only from reproductions; many have their own high-quality reproductions of well-known portraits. The smaller, underfunded museums necessarily place great reliance on photographic reproductions for their displays, but these too may yield some surprising images: photographs at Brasov show Dima riding a camel in the Egyptian desert, and at Ergli in Latvia the four Jurjans brothers in their boat, serenading the villagers from the lake with their quartet of french horns.

It has been popular since the 19th century to make plaster and metal casts of pianists hands. Reproductions of the right hands of Chopin and Liszt can be seen at every shrine to them and sometimes at those commemorating their admirers. Most moving of all is the pair cast from moulds of the hands of the violinist George Enescu, taken late in life and exposing extensive gnarling caused by arthritis.

Sculptures from life and death masks may also effectively reduce the distance between the vertices of the triangle formed by viewer, effigy and subject. The terracotta bust by Roubiliac in the Gerald Coke Handel Collection at the Foundling Museum records the very pores and texture of Handel’s face; the approaching visitor becomes aware that he would never dare venture so close were it the man himself. As with Roubiliac’s more intimate Vauxhall Gardens statue, ‘Handel as Orpheus’, one half-expects, half-fears, that the composer will utter one of his pungent remarks at any moment. Death masks, at the time considered an important record of the end of life, may now poignantly convey an image of age and illness, as in the cases of Haydn, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner and many others, and may strike some viewers as a gratuitous invasion of privacy. The juxtaposition of Beethoven’s life and death masks in the Bonn museum is arresting. To many visitors the two death masks of Bellini, taken 41 years apart, may seem slightly macabre, exhibited along with documents associated with his final illness, his death, his burial and his exhumation and the purple velvet coffin in which he was initially interred, open for all to see.

Composer museums also collect and display unparalleled collections of images of their subject’s families, patrons and pupils, friends and colleagues. When arranged chronologically or in relation to the composer’s time in the particular house or the locale and the music he was composing, museum displays can offer fresh impressions of the composer and the nature of his life and his circle, until then perhaps only dimly perceived. That is certainly the case for Tansman at todz, for example, but also for many other 20th-century figures for whom large photographic archives exist.