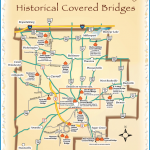

COVERED BRIDGE MAPS

It is little wonder that covered bridges have been called “kissing bridges” and “tunnels of love.” Set in bucolic landscapes, often off the beaten path, they have an aura of romantic seclusion. Yet the type had a purely practical genesis. Why were they covered? Not, as the story goes, so a traveler wouldn’t know what kind of village awaited him until it was too late, but because a bridge’s wooden supports lasted longer when protected from rain and snow.

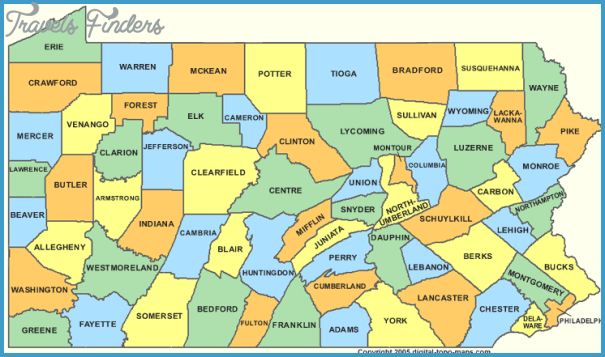

Sachs Covered Bridge (1852), Adams County, Pennsylvania

We crossed this river by a wooden bridge, roofed and covered in on all sides, and nearly a mile in length. It was profoundly dark; perplexed, with great beams crossing and recrossing it at every possible angle; and through the broad chinks and crevices of the floor the rapid river gleamed, far down below, like a legion of eyes.

COVERED BRIDGE MAPS Photo Gallery

CHARLES DICKENS, ON CROSSING THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, 1842

There was economic demand for bridges too. A burgeoning young America desperately needed ways to cross her many rivers and streams; goods had to be traded, mail carried, political and social aspirations forged. Some thought the federal government should undertake such “internal improvements” as bridge building, but Washington was too green for that. So the task fell to an eclectic group of entrepreneurs who took timber and one basic design elementthe triangular-shaped trussand created a truly American bridge, one unlike any built in Europe.

Beautiful in themselves, the intricate truss patterns that emerged in the early nineteenth century also solved a practical engineering problem: how to build bridges that could span rivers without blocking the channels below. The patterns were named for their clever inventors, including Ithiel Town, Theodore Burr, William Howe, and Stephen H. Long. For the most part, these early designers were not professional architects but intuitive engineers with long experience.

Many were entrepreneurs who built bridges to simply make a buck. Public companies were formed, shares sold. Investors recouped their money by collecting bridge tolls. Even if those tolls were minuscule by today’s standards (two cents for foot passengers or cows, eight for a one-horse sleigh), they added up.

One such entrepreneur, the red-haired, long-nosed Ithiel Town (1784-1844), was a Connecticut architect who patented his eponymous lattice truss system in 1820. Strong, durable, and cheap, the Town lattice truss was enormously popular with builders. Town charged a dollar per foot for using his design with permission, two dollars without. Thanks to patent agents who aggressively hawked his design, hundreds of Town lattice truss bridges were built, many of them in New England (see here). It is estimated that more than ten thousand covered bridges were built in the United States between 1805 and 1885. But many of these bridges came down almost as quickly as they went up, their wooden frames vulnerable to fires, floods, and natural disasters. Why, then, were they made from timber rather than the more durable stone? Because lumber was plentiful and cheap, in some cases even free.

In the twentieth century, as the car replaced the horse and buggy and highways were built, covered bridges began to disappear at an alarming rate. By 1954 there were less than two thousand left. But just in time, preservationists and others recognized their charm. Those that remain are living pieces of history and also valuable tourist attractions. Celebrated in prose, poetry, and song, covered bridges represent a more innocent age when boys and girls swung from bridge rafters on summer days and placards inside the bridges advertised such popular remedies as Kickapoo Indian Oil, a “blood, stomach, kidney and liver regulator.”

Yes, some were used for smooching. According to the New-York Historical Society, Manhattan once boasted three bridges named “Kissing Bridge,” but they are long gone, buried beneath the city’s streets.