Helen’s childhood had been turbulent. Already her magnetic beauty had aroused such wild emotions that her mother was rumoured to be not Leda but Nemesis, goddess of vengeance, raped by Zeus at Rhamnous when both were in the guise of swans.

Theseus, determined to possess an immortal wife, abducted Helen to Athens when she was only seven. Although the Dioscuri rescued her, when she reached marriageable age Tyndareus again realized the dangers inherent in her loveliness. Sparta was besieged by ardent, volatile admirers, the highest-born and most ambitious heroes, each offering rich gifts in exchange for Helen’s hand. So passionate were they that Tyndareus feared for the stability of Helen’s future marriage – until Odysseus of Ithaca suggested a solution.

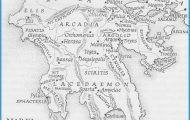

Taking Odysseus advice, Tyndareus assembled the suitors on the plain just north of Sparta, and commanded each to stand on the butchered carcass of a horse and swear an oath: they would unite against any who sought to undermine the marriage. Then he gave Helen to Menelaus. Some versions of the myth suggest he also passed his kingdom to him To Agamemnon, Menelaus brother and king of Mycenae, he gave Helen’s sister Clytemnestra.

Helen & Menelaus Photo Gallery

In return for his advice concerning Helen’s marriage, Tyndareus lent his support to Odysseus efforts to win his niece, Penelope, the daughter of his brother Icarius. Odysseus was fleet of foot, so Tyndareus suggested that Icarius give Penelope to whoever won a race through Sparta’s streets. The victor was Odysseus, but Icarius was loath to let the happy couple leave, and when they set out, he followed in a chariot, begging his daughter to stay. Loving her father but in love with her husband, Penelope was torn. But when Odysseus told her she must choose, she veiled her head in silence and continued on to Ithaca to be the model of fidelity.

A few years later Tyndareus forgot to sacrifice to Aphrodite, so the goddess enflamed Paris, Prince of Troy, with reports of Helen’s beauty and brought him to Sparta as a reward for judging her the fairest. Foolishly, Menelaus sailed to Crete, leaving them alone. When he returned to find his palace and bed empty, he sent messengers throughout Greece to remind Helen’s erstwhile suitors of their oath, and so the army sailed to Troy, and after ten years sacked the city. Helen, unbowed, returned to Sparta, where she continued to assert control:

At once into the wine, which they were drinking, she threw a drug, which would relax and soothe and take away all memory of suffering. Whoever drank the mixture would shed no tears that day, not even if his mother or his father were to lie before him dead, or if his brother or dear son were to be slaughtered right in front of him before his very eyes. So clever was the drug that Zeus daughter mixed, which Polydamna the Egyptian, Thoon’s wife, had given her.

While Eros hovers overhead and Peitho follows on, Paris leads Helen by the wrist from her palace at Sparta.

After his death, Menelaus was buried at Therapne on the plateau overlooking the Eurotas, where the Spartans honoured him as a hero and Helen as a goddess. As for the immortal Helen, a sixth-century bc Greek explorer from South Italy claimed to have met her on White Island in the Black Sea, where she was living with Achilles. She gave him a message to convey to the lyric poet Stesichorus, who had suddenly been struck blind after condemning Helen’s adulterous relationship with Paris. Now Helen promised to restore his sight if he wrote a recantation, so his Palinode begins: ‘The story is untrue! You never sailed in well-oared ships, nor reached Troy’s citadel. Immediately he wrote the lines, Stesichorus saw again. His explanation was that the gods, wishing to decimate mankind through war, yet preserve Helen’s honour, substituted a phantom for Paris to abduct. The real Helen was spirited to Egypt, where Menelaus found her on his voyage home.