This close inter-relationship between birds and people has probably been in existence for thousands of years. There are written accounts of it in the 17th century and early religious missionaries in Africa were surprised by birds that came to their altars and took pieces of wax from their beeswax candles. In Asia, 3rd century Chinese scribes wrote of little birds of the wax combs’ based on reports about the Yellow-rumped Honeyguide of the Himalayas, though they are not known to guide.

So how might their guiding habits have begun? There have been suggestions that the honeyguide/human link-up derived from a similar relationship between honeyguides and Ratels (Honey Badgers), attractive grey and black badgers common in much of Southern Africa. Very fierce mammals, Ratels can easily kill snakes, even venomous ones, amongst other animals. But they also have a liking for beehives and wild bee nests. Many experts doubt the badger/honeyguides mutualism because there are few or no confirmed sightings, at least not confirmed by Western eyes! Robert Lentaaya, though, is quite sure; he told me that he has seen a Greater Honeyguide leading a Ratel on several occasions. And I most certainly have no reason to disbelieve him.

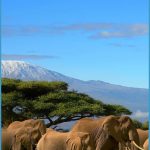

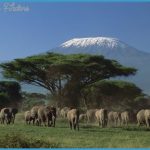

Kenya Wildlife Travel Photography Photo Gallery

A couple of days before I was due to leave the Mathews Range, another honeyguide made a chattering appearance very close to our campsite. And Lentaaya started talking to it, calling me over at the same time. We were off! This time I could more easily see the flicking tail as we walked fast under the forest trees and around some patches of impenetrable scrub. We even had to cross the Ngeng River to follow it, hopping from boulder to boulder but never losing contact with our guide. The bird very obviously slowed down at times to wait for us to catch up. Another couple of hundred metres, up a steep, wooded slope on the far side of the river and the chattering eased, the bird stayed in one spot and the characteristically loud hum of a colony of bees began to dominate the stillness. We spotted their nest only a metre or so above the ground on a rocky outcrop under the forest canopy. And, as Lentaaya cut a large branch from a nearby tree and trimmed it with his knife to make a sturdy straight pole, the honeyguide watched from some low branches just above us.

But first, the vital task of pacifying the bees. Lentaaya gathered together a large bunch of twigs and dry vegetation, tied it into a torch-shaped bundle, lit the end of it with a lighter he carried and blew out the flame. Carrying the smoking firebrand to the rock cleft where the bees were, he wafted it to and fro, subduing them just as a commercial beekeeper would. The humming quietened.

Then it was time for more physical action. He quickly jammed the pole into the nest entrance between pieces of rock, prised it suddenly to one side and, with an audible crack, the rock split open to reveal a cloud of highly agitated bees. I stepped back, fearful of stings. Lentaaya, smoking firebrand in hand and seemingly oblivious to any stinging, thrust it into the nest, drugging the bees quicker than I dared imagine was possible.

Quickly, he grabbed most of the honeycomb, depositing it in a bag he had carried with him. A small piece he threw on the ground nearby, and off we went. By now the bees had recovered; they were distinctly agitated once again, the smoke drugging rapidly wearing off. Their collective hum had become a threateningly loud drum-roll, and I for one was relieved that retreat was the distinctly more sensible form of valour. A little distance away we stopped to look back at the bee nest site. With binoculars we could see the honeyguide on the ground pecking away at its piece of honeycomb; silent now as it ate its fill of the food. The only sound was that of the highly agitated bees, their nest largely destroyed and a rebuilding or relocating task in store for them. No wonder they were buzzing loudly.

It had been an amazing experience; a huge privilege accompanying Lentaaya. Within a generation, though, this astounding and unique relationship between honeyguides and people might well be confined to history and story-telling. Few people, even among the Dorobo, now bother to follow the birds to honeycombs because many people now raise bees in hives at home. As people the world over become more and more distanced from a way of life in which nature is part of their everyday existence, such close relationships will become rarer still. Most will die out.

The birds themselves, too, might well decline as more and more woodland is felled for fuelwood and not enough is planted to replace it, although the best guider, the Greater Honeyguide, is a bird not of forest as much as more open ground with scattered trees. Nevertheless, trees are essential for these birds. They are often the location for the bee nests they crave. And older trees with rot holes and other cavities are the breeding places for barbets, starlings and woodpeckers in whose nests honeyguides lay their eggs, cuckoo-like, and let these foster families do all the hard work of raising their young for them.

No parental responsibilities, helpers to get much of their food, and lots of honey to eat into the bargain. Maybe it’s not a bad life being a honeyguide after all.