The first decade of the new millennium has seen a stabilising of visitor numbers at around 750 000 per annum, but with a steady increase in visitor spend. Operational costs have been contained by outsourcing non-core activities to service providers. Today, the Garden personnel totals 115 full-time staff, down from 160 in the 1990s. Non-core functions such as gate admission control, security and cleaning, are outsourced to service providers employing 22 contract staff. Many of the visitor amenities – restaurants, shops, tourist office, sculpture sales – employ a further 130 full-time staff.

So, while Kirstenbosch has been able to reduce its staff complement, the overall employment opportunities provided by the Garden have almost doubled. The Garden is now more fully integrated into the local economy than ever – no surprise that it has received several national awards for its outstanding productivity.

Pearson, in his famous 1910 Presidential Address to his learned colleagues of the South African Association for the Advancement of Science, proposed that a National Botanic Garden should engage in studies on the economic value of our flora that would undoubtedly do much to remove what is at present a national reproach as well as the neglect of what might be an important commercial asset’.

From its first days, Kirstenbosch was set up to garner financial reward from our flora. Pearson planted out the economic botany’ section – most especially of buchu – and equipped it with a distillery to produce buchu essence for the overseas market. Compton struggled on with the project, finally terminating it in 1939, the economic idea that failed’ as he later described it. During Eloff’s tenure, plant production was one of the four main objectives of the NBG, but because of resistance from the commercial horticulture industry – which viewed Kirstenbosch’s involvement as unfair competition – and inadequate funding for the project, this venture, too, failed. In Huntley’s tenure, attempts to select and breed new cultivars for the international market through a partnership with Ball Horticulture of Chicago led to a storm of protest and emotional remarks, including accusations that Kirstenbosch was selling the nation’s floral silver’. Ten years and many million dollars in investment later, Ball concluded that the jewels of South Africa’s indigenous flora had long since been plucked for the international horticultural industry, way back in the 18th and 19th centuries, during the heyday of botanical exploration at the Cape. The hard lesson learnt is that botanical gardens should not try to engage in commercial horticultural activities. These are best left to the private sector.

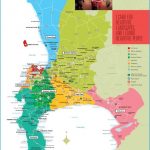

Kirstenbosch Map In World Map Photo Gallery

But there were many positive lessons from successful initiatives and approaches. First of these, for a public service institution, was one of image. The friendly face’ must not only have a smile – it must be professionally competent, dedicated and willing to go the extra mile. Kirstenbosch has been fortunate in having loyal, passionate and committed staff. Several staff members are third-generation employees, with many retiring after 40 or more years of excellent service.

A second key to Kirstenbosch’s success has been to win friends and cherish them The Kirstenbosch Development Campaign concluded: Building lasting friendships was the single most important strategy that we have followed’.

A third lesson came from the newly established democracy that transferred decision taking from a minority government to the people. Aligning strategy to government policy meant, in effect, keeping close to the people’. This was possible through working with the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee – which guides decisions at the highest levels of government. Hosting meetings of influential political actors has given them regular exposure to the Garden’s work.

Finally, the lesson that surprised us all was that a garden can reach financial independence if all its income-generating potential is carefully developed and nurtured. The turnaround in the financial and management models introduced by Huntley and Kirstenbosch Curator Philip le Roux in the 1990s places Kirstenbosch in the enviable position of being able to look beyond mere survival – the challenge that its directors faced for the first 75 years of its history. Long may this happy situation continue!

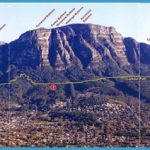

In an oblique aerial photograph of Kirstenbosch, the Visitors Centre, Conservatory, Millennium Glasshouses, Workshops and Garden Administration run to the left, parallel to Rhodes Drive, while the Garden Centre and restaurant lie on the mid-slopes above the main entrance off Rhodes Drive. (Photo courtesy of The Aerial Perspective)

The iconic Quiver tree Aloe dichotoma and other succulents in the Karoo Desert NBG grow below the snow-capped Brandwag peak outside Worcester.

Existing and proposed (Kwelera) National Botanical Gardens across South Africa

Harold Pearson’s vision of a national network of botanic gardens was not to be realised during his lifetime, nor during that of his successor, Robert Compton. But Pearson had recognised the need for at least one garden in each ecological region of the country – he thought that 10 might suffice. This plan was clearly in competition with that of Dr I.B. Pole Evans, head of the Division of Botany in the

Department of Agriculture, based in Pretoria, who had similar ambitions, as discussed in chapter 2. Compton, ever the gentleman, clearly decided against conflict. He did not press for more gardens, aside from the tiny Karoo NBG established in 1921, but the full weight of Pole Evans’ influence came to his attention with the establishment of a National Herbarium in Pretoria in 1923.