Rising anti-British feeling among Native Americans allowed diverse groups of Senecas, Shawnees, Delawares, and various Algonquin villages to set aside

former differences. In the winter of 1762, war belts traveled throughout Indian Country as Native Americans prepared for war against the British.

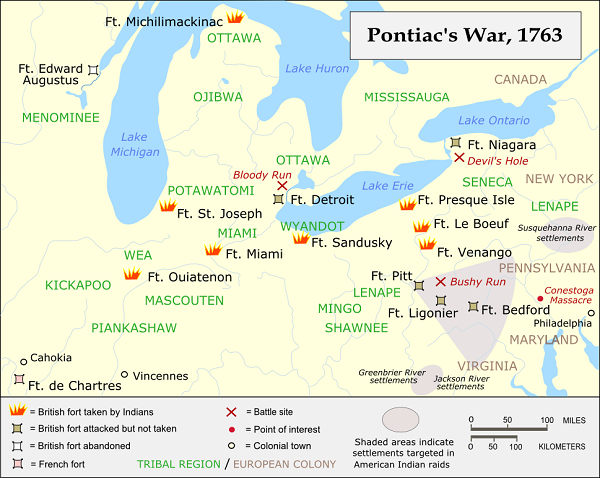

In the spring of 1763, war came. The Ottawa laid siege to Detroit, while other natives destroyed all of the British outposts in the Ohio River Valley. The

native warriors failed to take the three largest British installations at Detroit, Fort Niagara, and Pittsburgh but they inflicted a great deal of real and

psychological terror. By the end of the summer, they had killed several thousand settlers, traders, and British soldiers. When news of the situation reached

London, Parliament sent reinforcements and passed the Proclamation Act, a last-ditch effort to avert conflict along the colonial frontier. The British had

fought the native forces to a stalemate, and though sporadic fighting continued for a couple of years, no territory changed hands and the loss of life

lessened considerably.

Both sides of the Anglo-Native American conflict resorted to brutal tactics during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Pontiac seized a British captain under a flag of truce;

an Ojibwe leader later tortured the captain to death as revenge for a nephew’s killing. Jeffery Amherst, commander of British forces and a confirmed hater

of Native Americans, ordered his soldiers not to take any prisoners; he also gained notoriety for sending smallpox-infected blankets into native villages.

The results of Pontiac’s Rebellion were not decisive in favor of either the native peoples or the British. Native Americans had failed to evict the British

from the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley, as the British retained their three key military strongholds. On the other hand, the British had set out to

subjugate the Native Americans and subject them to colonial rule, and they had failed in that mission. Both sides gradually moved away from their hardline

positions (Amherst, for example, returned to England and was chastised for his brutality) and began to seek a meaningful, lasting peace in the years

after the rebellion.