Historical geography of the vine

The historical geography of the vine and wine in New Zealand is usefully viewed in a series of overlapping phases: the period of rural settlement

The country’s leading winemakers gather at the 1970 Viticultural Association field day. The association’s president, George Mazuran – a Croatian immigrant who had been growing grapes and lobbying government in New Zealand for more than 30 years – addresses the group. Marti Friedlander, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira, PH-2008-4 from the vine’s first known planting in 1819 through to the 1930s; the period between about 1880 and 1920 when the temperance movement and restrictive legislation contributed to reducing the small area in vines; a period of steady growth from a small base during the 1920s and 1930s and rapid growth during the Second World War, followed by a decade of uncertainty, even crisis, as local markets evaporated when imported wines again became available; and the most recent phase, from the early 1960s, when the planting of vineyards recommenced at an unprecedented pace and has continued through the rest of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, interrupted only by the vine-pull scheme of 1986. Changing societal and governmental attitudes, together with changing consumption patterns and changing marketing and distribution channels, have underpinned the latter developments, but this period of buoyant growth was founded on its past, and the period before 1960 reveals much about the culture-environment nexus of the vine and wine.

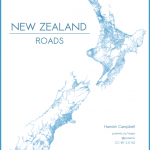

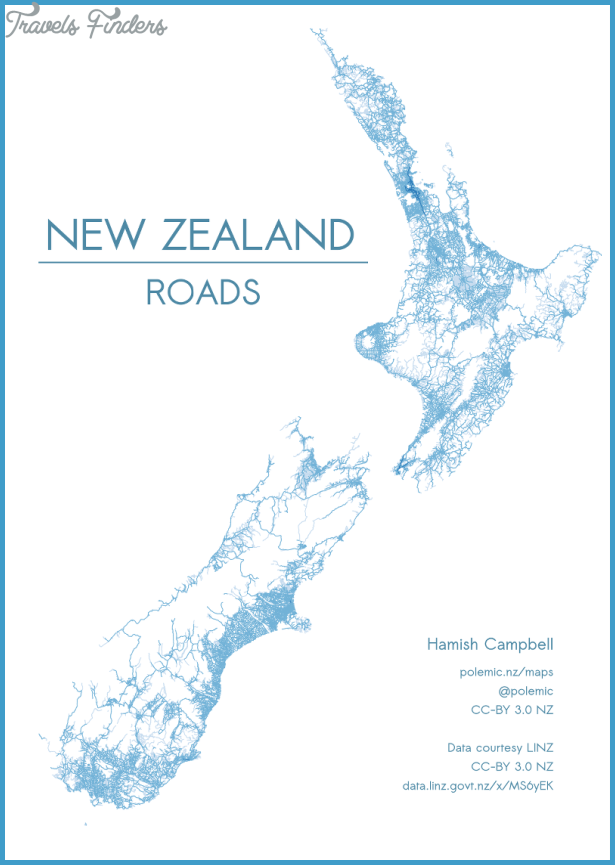

Road Map New Zealand Photo Gallery

The vine arrived in New Zealand soon after the first settlement by Europeans. Samuel Marsden planted vines; and James Busby made the first wines in 1836. Dumont d’Urville, when he visited Busby in 1840, praised the wine made from these Bay of Islands grapes. It is quite possible that the vine had arrived earlier than this, because ships plied the Tasman from the late eighteenth century and vines were growing in Sydney Cove by the 1780s. In 1838 the writer and explorer J. S. Polack reported that in New Zealand vines were ‘largely cultivated to the northwards of the River Thames -that is, in Northland and South Auckland. Maori were quick to cultivate them and supply table grapes to the Auckland and other markets as they seized the opportunities provided by concentrated populations.

As in most New World countries, the vine was also disseminated with the Catholic missionaries. The Marist Brothers established a winery in 1855 at Meanee in Hawke’s Bay, and later moved to Greenmeadows to become the Mission Vineyards. Sociologist and wine writer Jason Mabbett recounts plantings of vines by the Marist Brothers at Whangaroa, Otaki, Gisborne and on the Whanganui River, near Pipiriki. Wine was made from these grapes. During the second half of the nineteenth century and for the first two decades of the twentieth, when rural settlement spread rapidly, Vitis vinifera, like other crops of European origin, was planted in many parts of the country. Settlers experimented with various varieties as part of the mixed farming systems that they established. Most dairy farms, for instance, also had their own orchard until well into the twentieth century.

But the vine was not one of the perennial crops commonly found on all agricultural holdings of the predominantly Anglo-Celtic population. It usually appeared in one of two forms: as a family vineyard or vinehouse in the British tradition, usually for table grapes; or on land owned or used by people from cultures with traditions of wine the 1840 Nanto-Bordelaise Company of Langlois in Akaroa, the Spaniard Joseph Soler in Wanganui, Breidecker at New Plymouth, the Vidals of Hawke’s Bay, Croats from the Dalmatian coast on the gumfields of Northland and in other parts of New Zealand.

Colonial commentators frequently tied the vine to non-British cultural groups.