The high nave, looking east to the apse. The interior of Baker’s cathedral is much more beautiful than its exterior. Inside, it is strong and determined, unlike the outside, which seems unsure of what it wants to be. The archbishop’s throne, distant left, is made of wood from the choir screen in Westminster Abbey and given by Lord Nelson. ape Town was a distant outpost of the See of the Anglican Bishop of Calcutta. Without a church of its own, the congregation of the time used the Castle of Good Hope for their worship, or they borrowed the Groote Kerk.

But, on St George’s Day in 1830, a foundation stone was finally laid for a new church, its design based on London’s Greek Revival St Pancras. It would have a classical spire and a portico of Ionic columns topped by a hexagonal steeple freely derived, like that of St Pancras, from the Tower of the Winds in Athens. ‘It made one of Cape Town’s finest landmarks until it was demolished in 1954, says Hans Fransen in A Guide to The Old Buildings of Cape Town. Inside, it was a simple rectangular box with a gallery, a central altar and a side pulpit.

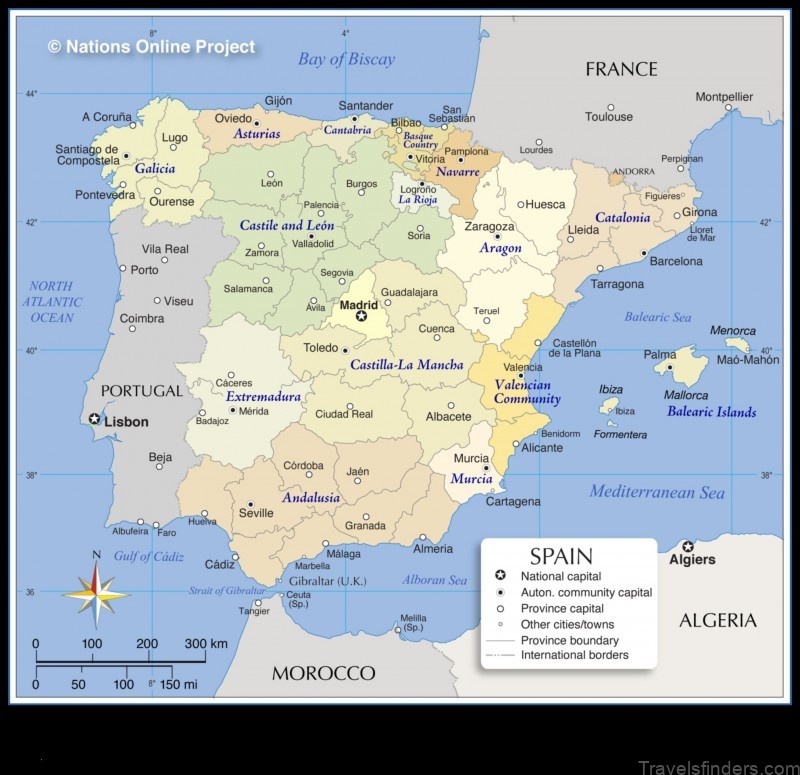

In 1847, Robert Gray was installed as bishop of the newly created Diocese of Cape Town and old St George’s became its cathedral, even though it was too small. Gray was unimpressed with its preaching box characteristics, and its design reminded him of a pagan temple at a time when Christian cathedrals were thought more suitably designed, said Pugin, in the Gothic style. A foundation stone for a new and enlarged cathedral was duly laid in 1901 by the Duke of Cornwall, and the foundations began in 1904. The architects were Herbert Baker and Francis Massey. Baker had by then already built a number of churches in Cape Town. His influence was far-reaching: he stressed simple forms and insisted on the use of ‘honest traditional materials like stone and wood rather than iron and plaster, and leaned towards Early English Gothic as an appropriate stylistic model.

The original plan had a nave with side aisles, a crossing, short transepts, a chancel flanked by chapels, and a rounded east end. The new building was set out along Wale Street at right angles to the old building, the tower of which had terminated the view up St George’s Street. The main entrance is through the north transept, which is unusual in a cathedral. The architect, aware both of the hot climate and the difficulty of obtaining good local stone, chose to light the building with small pointed windows. The stone is mostly Table Mountain quartzite, while the roof is covered with red clay tiles. Work was slow, and only in 1936 did St George’s begin to look anything like its architects had intended. In the interim, the Duke of Cornwall had became George V and the South African War, as well as World War I, had been and gone. Today it still isn’t finished; it’s missing the Gothic tower planned by Baker, which you would have seen as you approached up St George’s Street. The cathedral is now the seat of the archbishop of Cape Town.

In 1989, St George’s found its true place in history. At the time, it was the seat of Archbishop Desmond Tutu and, because of him, it has become a symbol of democracy in South Africa. It’s even been called the ‘people’s cathedral’, mainly because of events on September 13th, 1989. At the time, more than 30,000 people drawn from all races and creeds were led in a mass protest march from St George’s by, among others, the legendary Tutu. South Africans would no longer tolerate apartheid. Change was coming. It’s thought that Tutu coined an important phrase at the time: ‘And so we came to the cathedral to pray: Muslim, Jew, Christian, black, white – our rainbow nation – and as we walked out into the streets of Cape Town it was exhilarating to be joined by thousands, swept along in the realization of the dream that freedom is possible. ’

The rose window, erected in 1957 in the south transept, is by Frank Spears. The clerestory windows below are by Gabriel Loire.

Every viewpoint conjures up a substantial Gothic perspective. The stonework, the floor tiles and the wrought-iron work are authentic embodiments of prototypes found all over the English shires.

The stalls are made of stinkwood. In front sat the boys, behind them the men and further back the clergy. At the back, adorning the screen, are the arms of the dioceses of South Africa.

In St John’s Chapel, a monument to Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, British colonial secretary and architect of the Union of South Africa. It’s one of many notable memorials inside the cathedral.

Work began at the east end, at the apse, but it was only on completion of the north transept, in 1936, that Herbert Baker’s design began to come to life. Baker favoured tall narrow windows in an effort to exclude the brightness of the sun.