Paris had two passions: the mountain nymph Oenone, a skilful healer; and battles between bulls. His prize beast could beat any rivals, until a wild bull thundered into the ring. After a vicious duel it won, and Paris ungrudgingly placed the victor’s garland on its head. At once it changed its form, revealing its true identity: it was the war-god Ares. He had been searching for an honest judge to arbitrate a vexed dispute. He had found the perfect man.

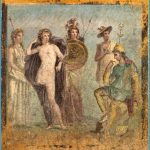

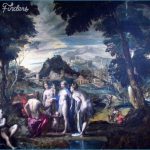

So, carrying the golden apple inscribed with the words for the most beautiful’, with which Eris had once disrupted Peleus and Thetis’ wedding on Mount Pelion, Hermes descended to Mount Ida with three goddesses: Hera, Athene and Aphrodite. Each claimed the apple for herself. Euripides’ Andromache tells how they came to win the prize for beauty, dressed for war, equipped for horrid strife, to the steading, to the isolated homestead, to the lonely shepherd boy. When they reached the dappled glen, they bathed their dazzling bodies in the mountain streams, and trading promises (so fulsome yet deceptive), they faced Priam’s son.’

On Mount Ida, Hermes leads the three goddesses – Hera, Athene and Aphrodite – to Paris for his judgment.

Paris could not choose between them. So each made him an offer. In Euripides’ Trojan Women, Helen of Sparta summarizes their terms.

The Judgment & Triumph of Paris Photo Gallery

The gift Athene promised Paris was to lead an army out from Asia and destroy Greece. Hera promised kingship over all of Asia and Europe, if Paris chose her. But Aphrodite, who admired my beauty and my body, promised that she’d give him me if he awarded her the prize.

Aroused by the bewitching goddesses, seduced by the prospect of Helen, and forgetting his love for Oenone, Paris awarded Aphrodite the apple and struck out for Troy.

He found the city celebrating games in memory of the royal baby exposed on Mount Ida twenty years before. Magnanimously Priam let Paris compete, and to widespread surprise he emerged as champion. Deiphobus was incensed and, with Hecabe, plotted Paris’ murder. But Cassandra recognized him – or perhaps the herdsman revealed his true identity – and, dismissing her dream as superstition, Hecabe with Priam welcomed their son Paris back to Troy.

Then, at the head of a magnificent flotilla and accompanied by his cousin Aeneas (the son of Aphrodite by Anchises), Paris sailed to Sparta to claim his prize. He rode inland from Sparta’s port to the royal palace. The late fifth-/early sixth-century ad epic poet Coluthus imagines Helen:

unlocking the doors of her welcoming chamber, running into the courtyard, seeing him standing there before the palace gates. At once she called to him, and led him in, and sat him on a new-made silver chair. And she gazed on him and could not satisfy her eyes with gazing.

Helen’s husband Menelaus entertained his guest lavishly. Then he departed for Crete. Within hours, Paris and Helen crept from the palace and that night on tiny Cranae, a stone’s throw from the coast, they made love. Then they set sail for Troy.

When Menelaus learned the news, he reminded Helen’s suitors of their oath to her father Tyndareus to help him should anyone abduct her. So they assembled a mighty army, led by Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and containing the greatest heroes of the age. Some, such as Achilles (from Phthia near Iolcus), joined reluctantly.

Achilles’ mother, the sea-nymph Thetis, coddled him from birth, purifying him in a fire, immersing him (held tightly by the right heel) in the River Styx to make him invulnerable, and sending him to Cheiron the Centaur to be educated. Now, knowing that he might die at Troy, she persuaded him to hide on Scyros at the court of King Lycomedes. But Odysseus of Ithaca, Nestor of Pylos and Ajax son of Telamon heard rumours of his whereabouts. Arriving at Scyros, they laid out a wealth of jewelry as gifts of friendship. As the women crowded round excitedly, Odysseus sounded the alarm as if the palace was under attack, at the same time throwing a sword high in the air. Instinctively a hand shot up and caught it. It was Achilles, dressed in women’s clothes. Sulkily he joined the expedition. (His mood was not improved when, at Aulis, Agamemnon used him as bait to lure Iphigenia to her death.)

The fleet attempted to make landfall at Tenedos, the island close to Troy, but it met with opposition. In the fighting Achilles showed his bravery, killing Tenedos’ ruler, Tenes. But when he discovered that Tenes’ father was Apollo, he remembered Thetis’ warning: if he killed Apollo’s son he would one day perish at Apollo’s hand.

From captured Tenedos the Greeks sent a demand for Helen’s return. It was refused. War was inevitable. So the Greek fleet nosed into Troy’s bay, where, after a brief skirmish, the Trojans withdrew behind the walls, the Greeks built a stockade around their ships, and both sides settled down for a long siege. For already Agamemnon’s prophet Calchas had predicted that Troy would be captured in the tenth year.