PONT DU GARD BRIDGE MAP

The Pont du Gard stands as testimony to the Roman genius for hydraulic engineeringand construction management.

Although the Romans were not the first to build bridges, they were the first to build large-scale bridges, a number of which have survived two millennia of warfare, flooding, and human intervention. Some of their greatest structures were aqueducts, designed to carry water, which was nearly as important to the Roman Empire as military conquest.

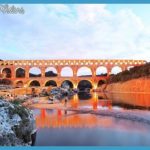

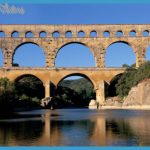

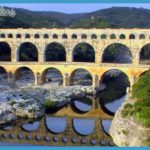

The largest and arguably the most beautiful Roman aqueduct is the Pont du Gard, completed in 18 B.C. Crossing the Gard River in southern France, it is part of an aqueduct system 31 miles (50 kilometers) long that once supplied water to the ancient city of Nemausus, now Nimes. Its massive size, coupled with its harmonious design and excellent state of preservation, make it a milestone in the legendary history of Roman engineering.

I ranged along all three levels of [the Pont du Gard], reverently, however, and hardly daring to trample it beneath my feet. I seemed to hear, in the echo of my footsteps resounding beneath those vast arches, the mighty voices of those who had built them. I was lost, a mere insect, in all this immensity. Yet, even as I saw myself grow small, I felt something, I know not what, that lifted my soul, and I said to myself, sighing: why was I not born a Roman!

PONT DU GARD BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

Given their facility with the voussoir arch, an art they appropriated from the earlier Greeks and Etruscans, the Romans could span almost any river. The Pont du Gard stands approximately 155 feet (47 meters) tall, the tallest of Roman bridges and an exception to the typical Roman waterwork, which channeled water at ground level or through underground pipes. It consists of two tiers of semicircular arches formed from stones, each cut to fit snugly against its neighbor, and a top tier, which is cemented. These wedge-shaped stones, known as voussoirs, when arranged in an arch exert a downward as well as an outward thrust. The bridge’s piers are only a fifth as thick as the arch spans are long, instead of the customary 1:3 ratio of most Roman bridges, giving the structure a slender silhouette surpassed only by the aqueduct at Segovia, which has a 1:8 ratio of pier thickness to span length.

It is generally believed that the Pont du Gard was constructed under the direction of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (63-12 B.C.), the emperor Augustus’s son-in-law and his highest-ranking general. Agrippa’s tenacity and technical competence saw the completion of major construction projects, first in Rome and then in Nimes, where most of the Roman ruins outside of Rome are located. In Roman Bridges, Colin O’Connor describes the complex hierarchy of Roman officials, architects, mathematicians, engineers, surveyors, militia, and laborers whose efforts were precisely orchestrated in an unprecedented building campaign that left the empire’s distinctive stamp on every corner of the then-known universe.

The bridge was constructed of soft yellow limestone, cut in the nearby Estel quarry and transported to the site by boat. In addition to masons, it required specialized workers, including blacksmiths, limeburners, and loggers. A misguided attempt to widen the Pont du Gard’s pedestrian passage in the seventeenth century almost caused its collapse. The bridge was restored, first in 1669 and again in 1855. Vehicular traffic, permitted until 1996, damaged the bridge; since 2000, access is only on foot. Protected since 1985 as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the Pont du Gard is an eloquent witness to the enduring legacy of Roman hydraulic engineering. The two lower tiers consist of broad arches; the longest one, which crosses the river, is 82 feet (25 meters) wide. The protruding stones supported scaffolding during construction.