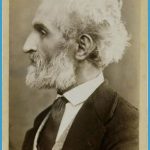

The Parma conservatory, one of the premier institutions of its kind in Italy, is called the Conservatorio di Musica ‘Arrigo Boito’, and it is there that the eponymous composer and librettist is commemorated. Boito was not from Parma himself, but in 1889 he went there to take over the directorship of the conservatory from his ailing friend, Franco Faccio. Born in Padua in 1842, he studied in Milan; he enjoyed only one substantial success as an opera composer, with the 1875 revision of his Mefistofele. His Nerone, left incomplete after almost 60 years of intermittent struggle, was given only in 1924, six years after his death in 1918. But he is remembered for his librettos, especially those for the Otello and Falstaff of his friend Verdi and that of Ponchielli’s La Gioconda.

BOITO MUSEUM Photo Gallery

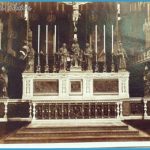

His study, based on the one in his brother’s house in Milan, is one of three studies preserved at the conservatory in Parma, whose structure around open, arcaded courtyards attests to its monastic origins. This and the Toscanini study are in a special museum area on the second floor, housed behind glass; the Pizzetti study is linked with the library. Installed in 1984, Boito’s sharply reflects his preoccupations. There are orderly bookcases, well stocked with a wide range of contemporary and classical literature, French, English and of course Italian. His notebooks are preserved, among them the jottings he took after visits to Verdi with a view to writing a biography. There are his librettist’s tools – two volumes of glossary and two of words arranged alphabetically by numbers of syllables. His ten boxes of notes on the composition of Nerone witness all too clearly the agonies he underwent. Much of his furniture is there: his desk, his working chair, his upright piano, leather easy chairs. A tuning-fork, a set of Helmholtz resonators and a set of piano-tuning implements bespeak his membership of a commission to determine pitch standards. There is a statuette of Verdi and photos of Verdi and others.