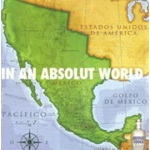

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Latino youth of Mexican descent reclaimed their ethnic identity and mobilized around it. Referring to themselves as Chicanos (a derivative of Mexicano and members of la raza, or the people) Mexican Americans used the label as a symbol of ethnic pride. As a politicized concept, the Chicano movement drew attention to the economic, social, and political marginalization of Latinos. Chicanos banded together to demand their right to fair treatment and equal access to education, political participation, and employment opportunities, as well as the right to claim membership in an ethnic community without prejudice.

In California, as in other places throughout the country, Chicanos mobilized around various causes, adding to the complexity and vibrancy of the multiple struggles that constituted the Chicano movement, which took root in the 1960s.

In part, these struggles drew on earlier examples of Mexican American activism. In 1931, for example, Mexican American parents called for a boycott to fight school segregation in Lemon Grove. Since the 1920s, Mexican Americans had also organized agricultural strikes throughout California in order to gain better wages. These precedents no doubt contributed to the defining struggle of the Chicano movement in California, which began with the efforts of labor organizers and the United Farm Workers Union (UFW).

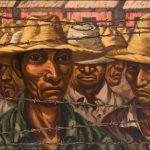

Bringing together the concerns of mostly Filipino and Mexican agricultural workers in rural California, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta shed public light on the plight of agricultural labor. Having experienced agricultural farmwork as a youth, Chavez knew of the inherent racial and economic inequalities. After serving in World War II, Chavez returned to California with a desire to change the quality of life of farmworkers. He gained valuable organizing experience in the 1950s working for the Community Service Organization (CSO) in San Jose. However, Chavez wanted to create an organization that would benefit farmworkers. Dolores Huerta, a native of Stockton, had also gained organizing experience through the CSO, and in 1955 she cofounded the Sacramento CSO chapter. Huerta shared a common drive to empower Chicano farmworkers.

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta cofounded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)later renamed the United Farm Workers Union Organizing Committeein Delano, California. The NFWA developed a strong membership of farmworkers who sought equality and justice and drew support from public figures and community members. In 1965 the NFWA initiated a grape pickers’ strike and later called for a national boycott of California table and wine grapes.

Five years later, in 1970, the NFWA scored its greatest victory when their strikes, boycotts, and other efforts finally won a contract with the largest grape growers in California. Subsequently, Latino farmworkers with NFWA contracts received higher wages and benefits.

The struggle for social justice and equality was not confined to the fields. High schools, colleges, and university campuses throughout California also became political battlegrounds for Chicanos. In their respective educational settings, Chicano students called for administrators to open the doors of universities to people of color, hire minority faculty, and include minority perspectives in their curricula.

The largest high-school student protest in the history of the United States is exemplary of younger student involvement in the Chicano movement. In 1968 more than 1,000 students peacefully walked out of Abraham Lincoln High School in Los Angeles with Chicano teacher Sal Castro to protest of the deplorable conditions in their school. This walkout sparked similar walkouts across Los Angeles in what is now referred to as the blowouts of 1968. In all, more than 10,000 high-school students walked out in protest of a lack of suitable school conditions, lack of minority teachers, and high dropout rates for Latinos.

Universities became another focal point of protest. Across California campuses, including UCLA, Berkeley, and Cal State Northridge, students and faculty pushed for scholarships for minorities, an increase of minority faculty, and the creation of Chicano studies. In 1969 a coalition of student groups meeting at the University of California at Santa Barbara established the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (the Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan), best known as MEChA. Throughout California university campuses, MEChA became a strong advocate of Chicano studies. MEChA continues to uphold the original goals of the Chicano movement and has chapters in nearly every university across the country.

The movement also confronted popular media representations of Mexican Americans, promoting scholarly, literary, and artistic productions that validated the identity and experiences of Mexican Americans. Rodolfo Acuna, a professor of history at California State University at Northridge, for example, wrote Occupied America, refuting widely held assumptions of Chicanos. Artists like Luis Valdez, who formed El Teatro Campesino (the Farm Worker Theater), also became active participants in the movement.