Convoy escorts, and anti-submarine patrols were out for long flights with continuous manoeuvring, such as square searches to be plotted. I took part in one sortie, in a Liberator which was eleven hours and forty minutes out. We proceeded to 25° W. in the Atlantic, and after an oblong search for ships boats, picked up a convoy on the return. Another day I joined a Fortress, for an eight hour thirty-five minutes flight into the Atlantic. I got into hot water with the captain of the aircraft for firing a burst from a -5 machine gun I was interested in, just as a corvette was passing below.

By the middle of 1943 I reckoned that I had written 500,000 words on navigation, and was becoming difficult to live or work with. I was offered a post at the Empire Central Flying School, with no official status and the rank of Flying Officer, the lowest commissioned rank except Pilot Officer. I accepted what looked like an interesting job. I was not allowed to do the sort of job I wanted, such as Navigating Officer at an operational station, because of my bad eyesight; and for the same reason I was not permitted to hold a General Duties post. I could only have an administrative job. I was not officially allowed to fly, not officially allowed to navigate, and I was not permitted to wear pilot’s or navigator’s wings on my tunic. One of the results of this was that whenever I visited an operational mess, unless I knew one of the members of the mess personally, I would soon be quietly edged out of any group of operational pilots talking at the bar. For my job at the Air Ministry I had been upgraded to the rank of Flight Lieutenant, but that was as high as I could rise.

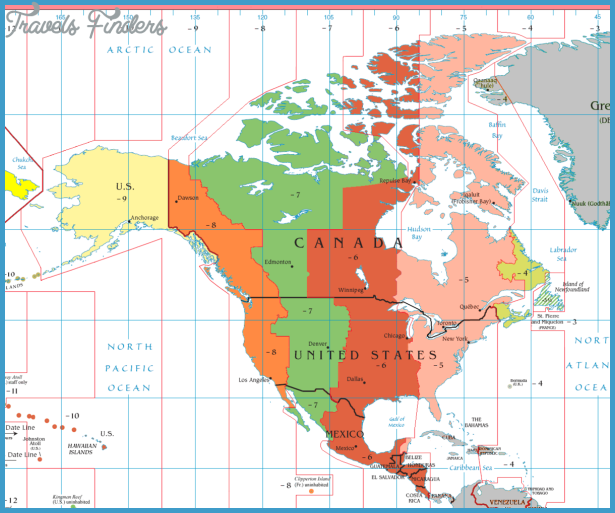

England Time Zone Map Photo Gallery

I arrived at Hullavington where the Empire Central Flying School was stationed feeling like a new boy at a public school. The standard procedure for anyone coming into the Air Force was to do an Officers Training Course. I had been moved straight into a uniform and into an office, and I knew little about the drill, customs and procedure. Hullavington was a big station – we had thirty-seven different types of aircraft there alone – and taking the parade as Duty Officer when the ensign was lowered at 6 o’clock was a formidable ordeal when my turn came. The last squad I had drilled was at my preparatory school in 1914. Naturally, I watched what the preceding Duty Officer did, but it was a very different thing to shout all the same commands in a parade ground voice to troops who were experts. It was a great relief to me when I found that I could get through it all right.

The Commandant at the Empire Central Flying School was a regular RAF Officer called Oddie, a stalwart character. He got himself into trouble with the Air Council because he believed in getting on with the war in the best possible way, and that regulations ought to be made to fit this purpose. After I had been there for ten days he put me into the Navigation Officer’s post to succeed Wing Commander Edwards, who was leaving for an operational tour. The ECFS ran courses for officers such as Chief Flying Instructors with ranks from Flight Lieutenant to Group Captain. They were mostly pilots drawn from every arm of the Service and from every ally. In one course we might have Fleet Air Arm, Army and RAF officers, together with Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Poles, Frenchmen, Norwegians and Americans.

My job, principally, was to brief them on the navigation of their flights, and to devise navigation exercises for them. At the end of each course we used to have a navigation race with twelve light two-seater Magister training planes in it. This was fine training for the sort of navigation that is really valuable to a pilot. We made it a kind of treasure hunt. For instance, in one race they had to fly to Stowe, the public school, and count the number of tennis-courts there, multiply the number by x, and then fly in that direction for 5 miles to find another clue. These races were immense sport, and very popular. I acted as pilot in one of them to Group Captain Teddy Donaldson, who at that time held the world record for high speed flights. He had to do all the navigating, and I simply acted as chauffeur. He swore afterwards that I had made him airsick for the first time in his life, but I think the truth was that it was the first time he had ever put his head down to look at a map in a cockpit.