ON A BRIGHT afternoon in early autumn, a shady green thicket of yew and holly trees can be glimpsed behind a plain wooden fence, which fronts a gap between houses on a 1960s’ residential development at Ware in Hertfordshire. This unassuming barrier hides a place of mysterious beauty in the form of a 250-year-old shell grotto cut deep into the chalk hillside. This amazing folly, which is now Grade I listed, was almost destroyed by builders 50 years ago, but has been saved for future generations to admire.

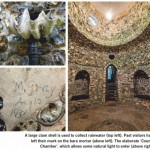

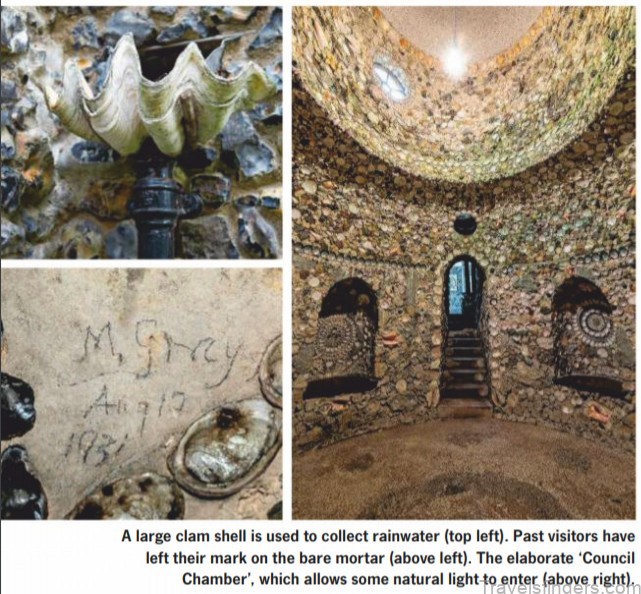

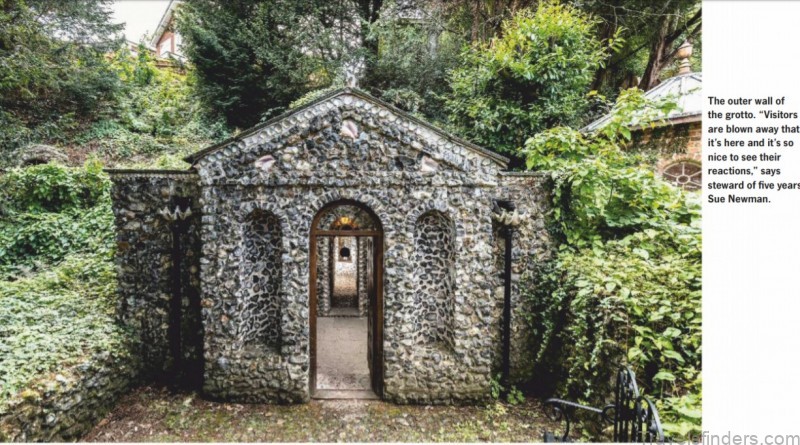

Once through the gate, the visitor descends a steep bank via flint-edged steps that are carpeted in spongy yew needles. At the bottom, a classical portico marks the grotto entrance, its walls coated in knobbly black and white flint pebbles. Large conch shells are embedded in the surface at key points of symmetry, and an octagonal cupola pokes through the vegetation behind. This is what the creator of this ornate network described as his “shell temple”.

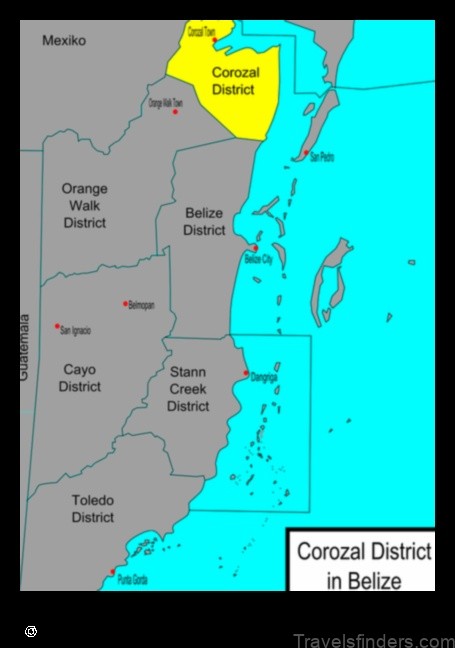

Map of The Hertfordshire Garden – Visit Hertfordshire Garden Photo Gallery

Fairy hall

Scott’s Grotto was the brainchild of a Quaker poet called John Scott, 1731-83, who created it during the 1760s and 1770s in the grounds of his family home, Amwell House, situated 20 miles north of London. “Most stately homes from the 1700s seemed to have a grotto, so it was clearly the fashion,” says Graham Watson, chairman of the charitable trust that now runs the site. In the 18th century, the well-to-do returned from the Grand Tour of Europe eager to replicate on their own property the elaborately decorated, Neoclassical grottoes they had admired in Italy. The idea spread around the country.

Grottoes had been popular on the Continent since the Renaissance period, when architects revived features from Greek and Roman times. These often included water features and shell decoration. “The question most visitors ask is: ‘Why is it here?’,” says Graham. “One explanation is that the Scott family had moved out from London, which was a day’s journey back then, and wanted friends to come to see them. So, to show them something, they built an attraction in their garden.”

It obviously worked, because Scott’s visitors’ book contained 3,000 signatures. Samuel Johnson, the most distinguished writer of his day, was one of them, hailing the grotto as a “fairy hall” when he visited in 1773. Another reason for the building of the grotto may have been down to Scott wanting to look after his workers during the winter, and the excavations it required would have helped with that, especially as the grotto is thought to have taken up to 30 years to fully complete. A contemporary biographer of Scott, John Hoole, was told by the poet that he had laboured on the structure himself.

He had “marched first, like a pioneer, with his pickaxe in his hand, to encourage his rustic assistants”, Hoole wrote. It is also likely that Scott viewed the grotto as a place to inspire poetic thoughts. Addressing a friend in his poem The Garden, he wrote: ‘From noon’s fierce glare, perhaps he pleas’d retires, Indulging musings which the place inspires.’

Subterranean passages

The original approach to the grotto was across a sloping lawn. Scott had laid out more than 6 acres of landscaped garden, planted with trees and shrubs, and punctuated with summer houses, rustic seats and paths.

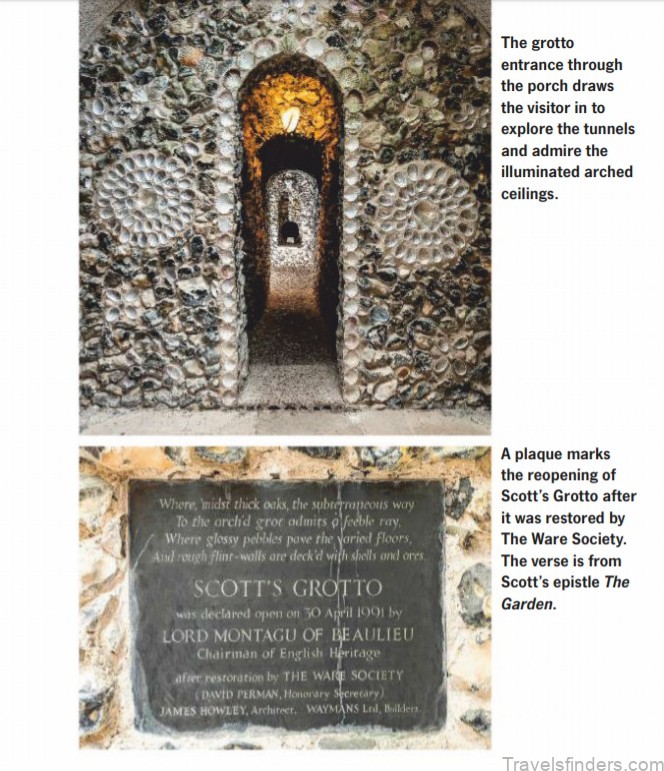

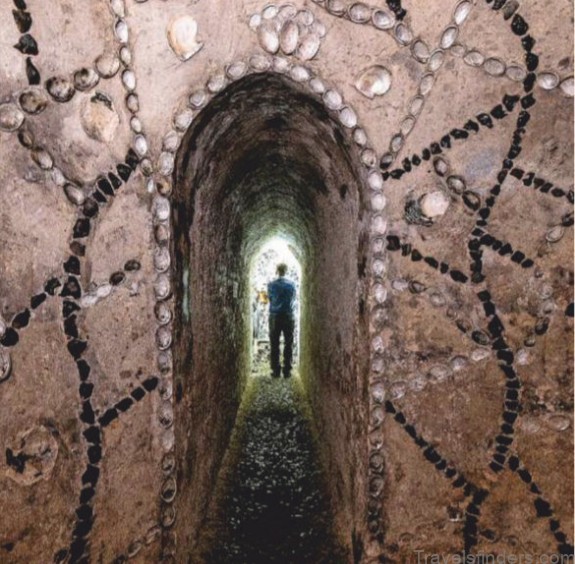

Housing developments in the late 1800s and 1960s carved up the land, and only approximately 0.25 acres remain. The house itself, now part of Hertford Regional College, lies 800ft (244m) away, but can no longer be seen from the grotto. Behind the main door, natural light enters a lobby through fan-shaped skylights, and the walls are ornately plastered in shells, pebbles and minerals, including patterns of shiny ormer shells from the Channel Islands. Beyond this, a web of subterranean passages links six domed chambers. The furthest excavations extend 67ft (20m) from the entrance, making it the most extensively tunnelled in the country. “It would all have been excavated with picks and shovels,” says Graham.

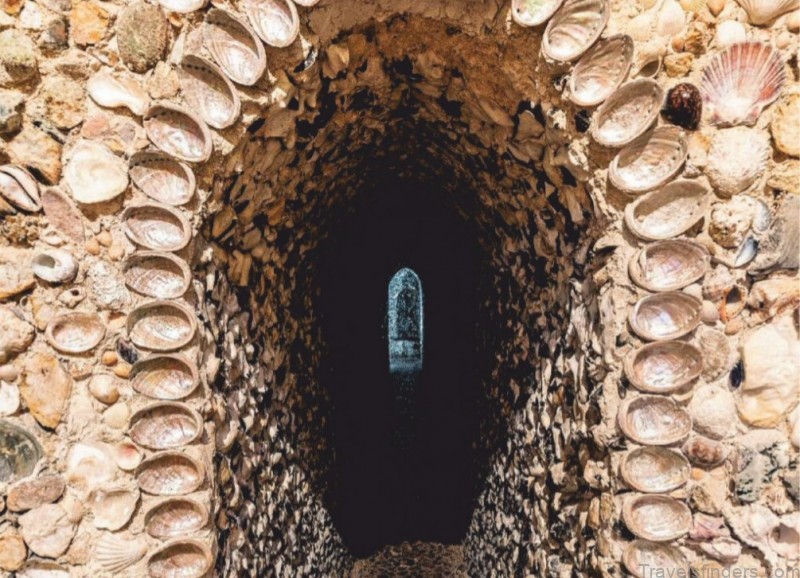

“We don’t really know where he got the design from, though I’m told he was influenced by Alexander Pope.” Pope, a fellow poet, had built a famous grotto at his Thames-side home at Twickenham in the 1720s. Heading off to the left, down four shallow steps, today’s visitor is soon plunged into darkness. The air also becomes noticeably chillier, dropping to approximately 10°C. The passage is barely 2ft (0.6m) wide and 6ft (2m) high. This one has a pointed arch shape, while others are curved at the top. It is surprisingly dry and odourless, and bats hibernate here in winter when the grotto is closed.

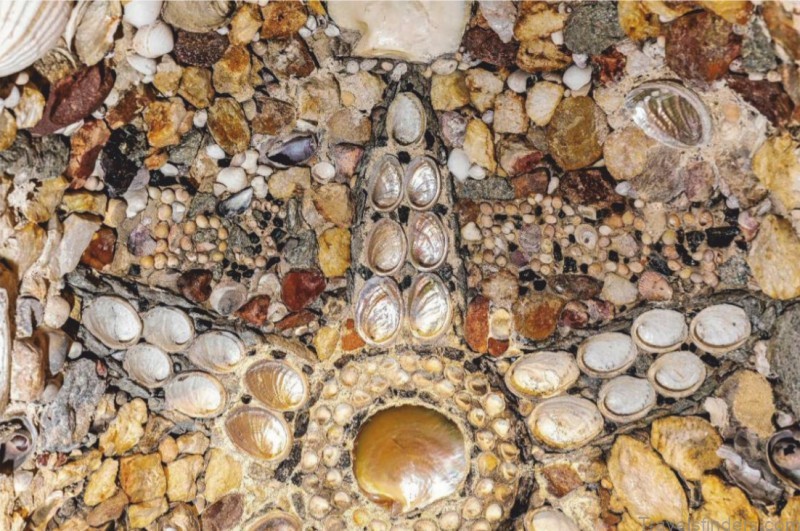

In Scott’s day, candles would have illuminated the grotto, casting a warm glow. Today, torchlight reveals that the walls and ceilings are completely encrusted in flint pebbles and shells, including large and exotic pink-tinged conchs, cowries and oysters from the Pacific and Caribbean. Flint is also embedded in the floor. The flint would have been unearthed during excavation, as it is a geological feature of the area’s chalky ground. “Scott had a friend who lived in Exmouth, and we think he got the shells for him when they came over as ballast on ships,” says Graham.

Some of the cockle and winkle shells, though, are likely to have come from Devon itself.

Flint chambers

The first chamber off this passage is circular and measures approximately 5ft (1.5m) in diameter. Like all but one of the others, it has several arched niches cut into the walls, with wooden seats. Thousands of shells are embedded within the flint stones, alongside chunks of stones and coloured glass. It is known that Scott wrote to a friend asking him to purchase melted glass and rockwork. The chambers were given names in late Victorian times by a local historian, R T Andrews, whose 1900 map of the grotto acts as a guide today.

He called this one the ‘Refreshments Room’. Two ventilation tunnels provide faint shafts of light and glimpses of greenery outside. A second chamber, off a short passage to the left, ‘Committee Room No 2’, is the only square one. In here, the flint walls contain patterns of a dark, iron-like stone that lends the room an austere appearance. The next passage, curving further into the embankment, is largely unadorned lime mortar, though it is not known whether or not this was deliberate or if it is simply unfinished. Off to the right is another ‘Committee Room’, which is also fairly plain in terms of decoration, with just the odd oyster and ormer shell amid the stonework. Further along, the visitor passes a niche topped with a heart-shaped motif in shells. The temperature drops a shade lower as the furthest and deepest chamber, known as the ‘Robing Room’, is reached, 34ft (10m) below ground.

It is the biggest so far at 8ft (2.4m) in diameter, and the knapped-flint and shell decoration forms serpentine lines across the mortar. “This room originally had a central pillar. You can see the remains in the floor,” says Graham. “It would have been shaped at the top like the spokes of an umbrella.” The chamber bears the imprints of past visitors, who have signed their names on the mortar. The earliest dates back to 1891.

Lavish decoration

The longest flint-lined passage leads back to the front of the grotto and the largest room, the ‘Council Chamber’, which is 12ft (3.7m) in diameter. It is lavishly adorned in 50 varieties of shells and minerals that glitter and twinkle. Although it is lit now by electric light, it also has fanlights in the dome, which would have let in some daylight in Scott’s day, when the garden was less hemmed in. The six niches in this chamber are decorated with different geometric patterns, including a star, a circle and an octagon, and the centre of the floor is inlaid with an octagonal pattern of pebbles.

Eight-sided designs were a popular feature of classical architecture. In one niche, written in small winkle shells, are the letters IoS and FROG. The first is for John Scott, with the letter ‘J’ being written as ‘I’ at that time. The second refers to Frogley, the maiden name of John’s first wife, Sarah. The stone includes quartz, mica and Hertfordshire puddingstone, which is formed of pebbles fused with quartz. A sea urchin and an ammonite fossil can also be spotted, and Graham points out a tiny pearl in one of the shells. An additional short central passage leads from the porch into the ‘Consultation Room’, which is almost entirely embedded with very chunky flint pebbles. “I would guess this was the first place Scott dug, because it’s a dead end and very basic,” says Graham.

Airy octagon

Heading outside and back up beyond the main gate is the rest of what remains of Scott’s once ample garden.

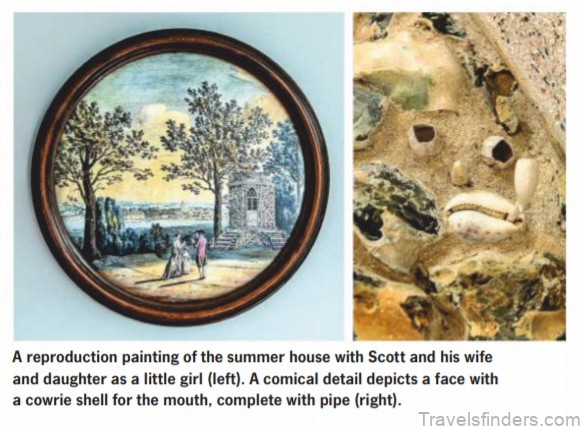

It is, as described by Historic England, “a small lawn largely enclosed by trees”. It has been left to naturalise, apart from occasional pruning. In the middle stands Scott’s flint-faced, octagonal gazebo, which is raised on a brick base, with a curved double flight of flint steps leading to the entrance. It contains reproductions of two paintings depicting the grotto and summer house in their heyday. One shows the view across to Ware church that Scott would have enjoyed from here, between two large oak trees. Today, the stump of one tree remains wedged into the steps and, a few paces to one side of the summer house, between the much-matured branches and 20th century rooftops, a small section of that view to the town is still visible. Scott described the building as “the airy octagon”. The local parish here was Amwell, leading to him becoming known as Scott of Amwell.

He wrote one of his best-known poems, Amwell, about the area, in the summer house, in which he describes the surrounding landscape, saying: “How picturesque the view! where up the side Of that steep bank, her roofs of russet thatch Rise mix’d with trees, above those swelling tops Ascends the tall church tow’r, and loftier still The hill’s extended ridge: how picturesque!”

Victorian marvels

When Scott died in 1783, Amwell House passed to his daughter, Maria. After her death in 1863, the property was divided up, a road was built through the grounds, and the grotto became part of the garden of a new house. It was opened to the public in the late 19th century by a Mr N Harris, who talked it up grandly as containing “Marvels of Taste!”

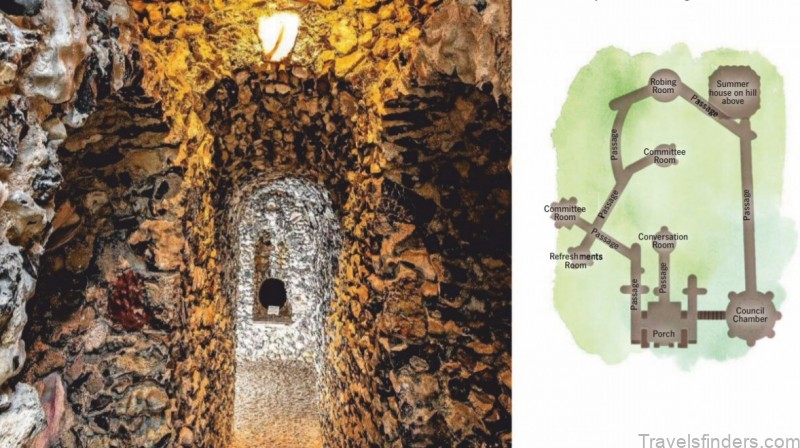

A flyer shows that he charged 6d, 5p, a visit and served tea in the grounds. In the 1960s, this house was knocked down and a new housing estate built. Two houses were planned for the land that the grotto occupies, and the porch, cupola and gazebo were all damaged before the building work was eventually stopped. “It finished up in the hands of the local authority because I think the developer discovered it would be extremely difficult to build on such a steep site with a rather large hole underneath,” says Graham. In 1983, after carrying out basic repairs, East Hertfordshire District Council put it in the hands of The Ware Society, a local organisation dedicated to preserving the town’s heritage. It opened the grotto to the public, then, in 1990, initiated a full-scale restoration designed by Dublin-based architect James Howley, at a cost of £124,000.

Careful restoration

Howley and his contractors worked from old photographs and salvaged materials to recreate demolished parts as accurately as practical. Although much of the grotto has survived intact, he describes the state of key areas as “very poor” when he first saw it. “The original masonry dome of the ‘Council Chamber’ had collapsed and been poorly repaired, and a lot of the shell decoration had been lost,” he says. “The original porch had also collapsed, so a new porch was designed in the spirit of the original, but larger, to allow an enclosed space for shelter and for tours to start and end.” The passages would have been open onto the garden originally, allowing more daylight to enter. Salvaged and new shells were fixed on with lime mortar.

A string of grey pearl oyster shells from Japan were among the many donations. A few quirks added by restorers include a small chunk of the Berlin Wall, which had just been pulled down, and a couple of hidden faces depicted in shells. Howley initially thought the summer house would need to be completely rebuilt, but English Heritage insisted on salvaging as much as possible. “The summer house was held up only by some chain-linked fencing forming a brace but, in the end, we saved 80 per cent of the original flint masonry and 215 years of patina,” he says. To retain the integrity of the structure, a modern block wall was built inside and faced with lime mortar. The woodwork had rotted, but was recreated from remaining fragments.

“The only visual difference between the original and repaired summer house is the thickness of the walls,” says Howley. The grotto site was reopened in 1991 and is now run by the Scott’s Grotto charity, set up last year by East Herts council and The Ware Society. “Scott’s is up there with the very best; a structure of international cultural significance,” says Howley, who has surveyed and restored more than 50 grottoes. “It was a magical project in every way.

ARTIFICIAL CAVES

At least 200 surviving grottoes have been documented in Britain, according to author Hazelle Jackson in Shell Houses and Grottoes, though many are overgrown ruins. Scott’s is one of the best preserved. The Oxford English Dictionary definition of a grotto is an “artificial ornamental cave”. That would suggest an underground site, but the earliest shell ‘grottoes’ in Britain were indoors. In 1624, James I had one built at his drinking den at the Banqueting House in Whitehall. The Shell Room at Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire also dates from this period. Rustic outdoor pavilions were also fashioned into grottoes as features of landscaped gardens. One of the most talked about in Georgian Britain was at the Surrey home of the Duke of York: Oatlands Park. Running into the hillside, the two-storey structure was lined with exotic shells and stalactites, and included a gaming den and a bath. It was visited by composer Joseph Haydn in 1791, who considered it “remarkable”. It was demolished in 1947 after the local authority declared it unsafe.