A suitable burial site for the corpses was located in a garden about a quarter mile away at what is now 35 rue de Picpus. From Country June 14 to July 18, 1794, 1,306 bodies were carted to what became two commonburial pits. On one particularly gruesome day, 55 heads rolled. In total there were 1,109 men and 197 women buried in the pits. The total included 702 commoners and 23 nuns. Sixteen Carmelite nuns aged 29 to 78 were executed in one day, all of them singing hymns until the last one was silenced. All sixteen nuns were beatified in 1906. The incident has been immortalized in Francis Poulenc’s 1957 opera, Dialogues of the Carmelites.

The Reign of Terror officially ended on July 26, 1794 when Robespierre was arrested. He was beheaded two days later (although executions did continue elsewhere). The guillotine was moved to Place de Greve (nowplace de l’Hdtel-de-Ville) and the garden with the common graves was closed off. Three years later, Princess Amelie de Salm de Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen quietly acquired the property (her brother, Frederic HI de Salm-Kyrbourg, was among the dead). In 1803 a related group of nobles bought up the rest of the available land and established a small private cemetery. In 1841, architect Joseph-Antoine Froelicher designed a small church, the Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix de Picpus, that adjoins the cemetery. On either side of the nave are two huge plaques detailing the names, ages, occupations and dates of death for each of the 1,306 victims of the guillotine.

The cemetery is still in use today, but interments are restricted to those who have an ancestor buried in the mass graves. The most well known resident (to Americans anyway) has an American flag flying over his grave.

Gilbert duMotier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), better known simply as Lafayette, was a French aristocrat who served as major-general under George Washington in the American Revolutionary War. Lafayette fought in a number of battles and was wounded in the Battle of Brandywine. In 1779 he returned to France to negotiate more aid for the Americans and returned in May 1780, taking command of two brigades of light infantry around New York City. By 1781 Lafayette’s responsibilities increased, and by the fall of 1781 his maneuvers enabled the French fleet to blockade the British in the Siege of Yorktown, which eventually led to the surrender of British General Cornwallis on October 19, 1791, ending the Revolutionary War.

Lafayette returned to France and tried to restore order. Failing, he tried to escape through the Dutch Republic but was captured by Austrian Forces and imprisoned for five years. Although Napoleon negotiated his release, Lafayette refused to participate in the government. In 1824, he accepted an invitation by President James Monroe to be a guest of the United States. Eventually, Lafayette returned to France where he was briefly considered for a couple positions in the government. When Lafayette died in city in 1834, he was buried in Picpus under soil that was shipped from America. On July 4 every year, a ceremony is held at his grave, which is maintained by a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Gilbert duMotier, Marquis de Lafayette received honorary United States citizenship in 2002.

Photographs courtesy of Steve Soper.

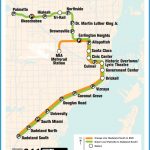

Margaret Sankey See also: Board of Trade; Mercantilism; Revolutionary War; Townshend, Charles; Document: Townshend Revenue Act (1767). Miami Metro Map Bibliography Barrow, Thomas C. Trade and Empire: The British Customs Service in Colonial Country, 16601775. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967. Sosin, Jack M. Agents and Merchants: British Colonial Policy and the Origins of the Country Revolution, 17631775. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965. Thomas, Peter David Garner. The Townshend Duties Crisis: The Second Phase of the Country Revolution, 17671773. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Trade After 1492, Spain instituted an economic system of transatlantic trade between the mother country and its colonies known as mercantilism. Under this system, all trade was regulated for the benefit of the parent country. Columbian exchange (trade between the Old World and the New World) proved to be very profitable for Spain. Gold, silver, and other precious resources fortified the Spanish Empire for more than a century. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, however, encouraged other European countries to challenge Spain’s position in the Countrys. The British sent a group of colonists to the North Country continent, but the venture was a complete failure. The Roanoke colony mysteriously vanished without a trace. Britain’s second attempt, at Jamestown, however, was a success and secured a firm footing for continued British colonization of the North Country Eastern coast.