By the time I left him the taxi driver and I had spent two hours together. Unusually for Burma he had a fair command of English and we had some conversation. He asked me if Burma was known in Australia. Tentatively I said that Aung San Suu Kyi was known. Not so long ago merely speaking her name got you a gaol sentence, and I was still cautious about saying it. But he beamed and showed me her photo on his phone.

He dropped me at the market where I bought a painting from the crippled boy who is always there, haunting the entrance. He hobbles along on crutches and seems to have a displaced hip; one leg is withered and hangs loosely at an angle. I had fobbed him off on all my previous visits but this would be my last. Then I ate lunch in a market cafe where I gave a donation to a pink-robed Buddhist nun in return for a blessing after watching her be rudely dismissed by two horrible Europeans. Later I passed a tiny, very old nun, and, seeing that her small begging bowl was empty, I chased after her and dropped a couple of notes in it. As I did, I looked up to see a stallholder smiling at me. People sometimes did this when I gave to beggars too, so I think it was okay.

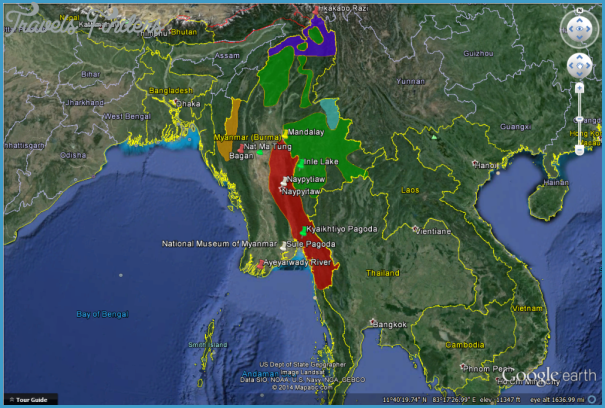

Myanmar On World Map Photo Gallery

I walked across the road to where I had been told there is another market, but didn’t find it. I went in an ornate gate that I thought could be its entrance, but was met by a man who indicated that I should have my shoes off as I was actually entering a mosque. I backed out and walked on, thinking I was heading towards the Queens Park Hotel, but when the Sule Pagoda appeared at the end of the road I knew I wasn’t. I ended up on the waterfront, having gone in the completely opposite direction. Why do I keep trying? Perhaps because on the rare occasion that I get it right it gives me such a thrill.

This day was Saturday and downtown Yangon’s streets were packed with people. There were countless small street stalls and one lane I went up had second-hand electrical bits and pieces strewn on the ground. Another wide street’s broken and lumpy but tree-shaded footpaths were covered with groups of men sitting on low stools clustered around small boxes commandeered as tea tables. On them sat pots of tea and small handle-less cups like saki cups. This seemed to be some sort of club. Then someone asked me, ‘You want stones?’, and I realised that they were discussing, and probably dealing in, jade or other gems. I saw only a little produced; maybe that came later when the tea drinking was over. These groups continued for miles.

As I walked I watched the sky become darker and darker and a huge inky cloud gathering, approaching from the sea. Time to give up walking. I hailed a taxi and rode back to Motherland with a driver who told me that he was from South India where people who had been to Australia to work in films had told him about our cheese and milk products. This was what I missed most from home cheese. Order cheese on something here and you got those appallingly uncheese-like plastic-wrapped slices. And at about a dollar a slice.

It started to rain as I left the taxi at Motherland, and it was dark and thundering so I decided I was finished for the day. As this was my last day I used all my remaining phone credit to call home and check on the cat. The cat said she was fine. The phone credit had lasted all the time I was in Burma, pretty good for a twenty-three dollar card twenty-eight days of local and one international phone call.