HUNTING A FORTUNE

When I left England I had made up my mind that I would not return until I had saved £20,000. Gold digging showed no sign of bringing me closer to this target. One day in the pub a man said to me, ‘Why don’t you become a book agent? ‘What’s that? ‘A man who calls from house to house selling books. A lot of money can be made at it, but you have to do it in Sydney.’

So once more I set off for Australia. On the way through Christchurch I called on the editor of The Christchurch Press to try to sell him my story of the gold strike. He said that he was always getting such things and wasn’t interested. He did, however, buy a snapshot of a gold dredge that I had taken, and for which he paid me five shillings.

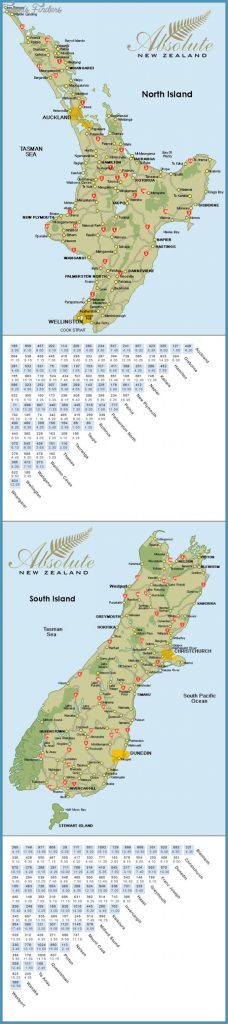

New Zealand Map Distances Photo Gallery

When I told him what I was going to do he said, ‘Why not sell the Weekly Press? So bang went my second attempt to reach Australia. I went north to Wellington, and started canvassing from door to door for yearly subscriptions to the Weekly Press. The arrangement had been that I was to get a commission and travelling expenses but his accounts department must have been surprised when I immediately started earning £400 a year in commission and they ‘reneged on the expenses. That was not my style, so I quit.

Then I was offered a job selling a book-keeping system to farmers. Five guineas covered the cost of a ledger and two years making up of income tax returns from it. I was sent out with the sales manager to learn the job, and I was eager and impatient to start. When my opportunity came, I went through my sales talk to a farmer and at the end he had agreed to take on the system and said, ‘What about a cheque for you? ‘Oh, I said, ‘you’ve already signed it and it’s in my pocket.’

This was a tough job, and only one other salesman beside myself, out of sixty-one, stuck it for a year, which was the target I had set myself. I found that if I could visit five farms in a day,

I was fairly sure of making two sales, but if I could go to as many farms as I liked I would make no sales at all. To get round the country I bought a motor-bicycle. I had looked forward for a long time to having one. This motorbike had a clutch but no gearbox, and could be started only by running it along the road. I set off from Wellington, and the first obstacle to climb was the Rimutaka Range. I climbed 7 miles up these hills, until I reached a sharp corner that was protected from the wind by a high palisading on each side. The wind funnelled down that gully in gale blasts, and some cars had been blown over the side. At this corner the wind stalled me. I could not restart the motor-bicycle by running up the steep hill; when I started it downhill, and then turned to head uphill, the engine stalled as soon as I let in the clutch. I was a hot man before I gave up, and coasted back to the bottom to start afresh. Next time I came up with a rush and, knowing the hill better, I got round the corner and over the summit. When I reached the Up Country in the middle of North Island, where I was due to start work, most of the roads were still unmetalled. The surface was volcanic clay, and became so greasy after a shower of rain that the back wheel skidded to one side or the other and the motorbike would not stay on the road.

I turned up in Taihape again, and bought an old Ford five-seater, with a hood. I paid £120 for it. It was worth £60, but I was new to business. I added a bicycle and a tent to my gear, and set off in the car. My technique was to drive to a new territory, and pitch camp there. I got so used to this that within twenty-five minutes of stopping the car, I could be lying on my folding campbed ready to sleep after unpacking the gear, driving tent pegs in all round, erecting the poles and rigging the tent, laying out my gear and the campbed inside, and getting undressed. Next morning I would set off on the bicycle.