While little is written about his life and ministry, it is with his martyrdom and burial that the legends seem most concerned. We celebrate St. James day on the 25th of July, being the day he was beheaded by Herod on his return from Spain to Jerusalem c. 40 A.D. Again. El Padron features widely as the place where the boat carrying his mortal remains tied up for the last time to the quayside. The city that bears his name was not yet born, for his disciples had no idea where to bury him. The city that now bears his name was known as Libredon.

Compostela is variously translated from Latin as campus stellae (field of stars) or possibly composta derived from componere (to bring together or to bury). The first translation comes from the understanding that the place where the cathedral now stands was a pre-Christian (Roman) burial site. The second connects the legend of the hermit Pelayo who saw in the 8th c. a star hovering above Libredon. He told the bishop of Iria Flavia, who subsequently excavated the site and found the tomb of Sant lago and that of his two disciples, Atanasio and Teodoro. The discovery was immediately authenticated by the Pope and Santiago Matamoros became the symbol of the reconquest of Spain in the 9th c. This Jed to the first pilgrims coming to Spain in the 10th c. the bishop ofPuy, Godescalco, arriving in 951.

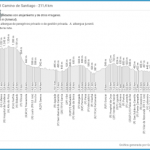

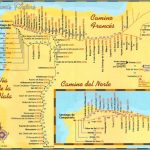

Santiago de Compostela Map Distances Photo Gallery

In their search for a suitable burial plot, the disciples of the martyred saint were directed to Queen Lupa, of fierce wolfish’ fame, who ruled from her nearby court at Castro Lupario. Various myths surround their reception there, but all speak of duplicity and the gifting’ of wild bulls to pull the funereal cortege, with the evil intent that they would turn on the disciples and kill them. Like all good stories, the animals became docile and Lupa converted to Christianity. However, according to the Codex Callixtinus, she sent the disciples to the king’ at Dugium and it was he who decided to have them killed. It was while fleeing over the rio Tambre (down river from Ponte Maceira) that they were saved by divine intervention as the bridge collapsed killing their pursuers. The king of Dugium would most likely have been the Roman legate, further evidence of the existence of a major centre of Roman administration in the Finisterre area at that time. Other interpretations suggest that the king’ was none other than the mythical lord of death’ himself.

Continuing the ever popular theme of death and dying is the ominous name given to this coastline: Costa da Morte (Coast of Death). This was perhaps more a reference to the cult of the dead or the Celtic Otherworld than to any basis on the fact of its manifold shipwrecks. It is not difficult to imagine Sant

Iago and the other early Christian saints and missionaries being drawn to this place so revered by pagans, Celts and Romans alike. The myth of the Head of the Roman Soldier is probably of more recent origin. Here, at Cabo de Nave the rocks form an outline in the shape of a ship (Nave), its prow facing West and heading into the Atlantic. Many myths refer to a boat that carries the souls of the departing to Nirvana. The other image conjured up by the shape of the small island (Berron da Nave) that appears as part of the headland is of a helmeted Roman soldier. His body laid to rest with his head lying to the west. Even George Borrow becomes somewhat mournful as he arrives at the Costa da Mort. He writes: It was not without reason that the Latins gave the name of Finis Terrae to this district the termination of the world, beyond which there was a wild sea, or abyss, or chaos . Those moors and wilds, over which I have passed, are the rough and dreary journey of life. Cheered with hope, we struggle through all the difficulties of moor bog and mountain, to arrive at – what? The grave and its dreary sides. Oh, may hope not desert us in the last hour – hope in the Redeemer and in God!’