With a swift jab of my knife to its brain, I watch its neon-purple stripes fade and retractable dorsal fin go limp.

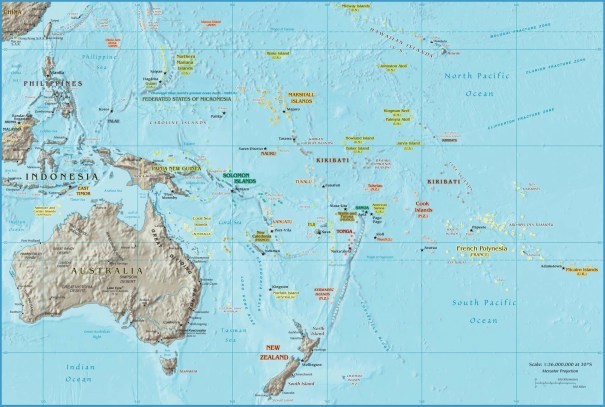

An hour later I find myself in a nervous fluster, approaching my first atoll pass. My Charlie’s Charts guideblog explains, “A pass is a break in the circular coral atoll that, if deep enough, allows entrance into the calmer waters inside the atoll’s interior lagoon.”

The blog also describes this particular pass as “difficult, with only a forty-five-foot wide channel and currents reaching velocities of six knots or more.” I’m supposed to enter the pass “on slack low tide with overhead sun.” I have neither. To further complicate the situation, a line of black thunderheads tailgates me toward the entrance. Should I stay another night at sea? I’m exhausted. Another full night of vigilance in these dangerous waters seems unwise, but what if Swell is swept onto the reef? Dad and I had tried to secure insurance for Swell but couldn’t find a company to accept a twenty-seven-year-old solo female captain, so regular maintenance and prudent choices are my best insurance.

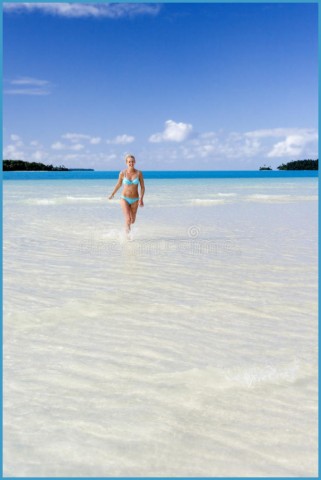

South Pacific Surf Vacations & Trips Photo Gallery

I approach the pass cautiously, but when the ocean floor leaps up to eighty feet and I spot a small patch of sand, I toss my anchor and hope for the best. It’s going to be a long night. The northwest wind has died, but it left a sloppy bump on the sea and Swell rolls and bucks unpredictably. If the wind comes up from the west as it did the night before, I will quickly be in a dangerous position against the lee shore. I anxiously shuffle around on deck, furling the mainsail, coiling ropes. A flock of children on the beach wave and holler while three humpbacks surface not a hundred yards away, but I’m too nervous about my anchor arrangement to appreciate the marvelous welcome.

A small fishing boat comes out of the pass headed for sea. I wave the fisherman over, dart below, and return with a bag of tuna steaks from my catch that morning. I have much more than I can eat and this weather is no good for drying it. The enormous Puamotu man flashes a toothless smile, accepts the bag, and asks me in French why I’m anchored outside the pass. The audio lessons are paying off, because I understand enough to attempt a reply.

“Peur. Ja’ipeurI” (I’m scared!) I explain. He laughs and signals for me to follow him through the pass. Thankfully the anchor comes up without a snag, and I line up closely behind him. The outbound currents churn and yank Swell’s bow to port, then starboard. I leap like a frightened cat when a small standing wave crashes over the stern, spilling across the cockpit. The engine is at full throttle, but we’re barely making a single knot of headway. The fisherman patiently remains just ahead of Swell, looking back now and then to make sure I’m advancing. I smile through my clenched jaw and stiff spine, as Swell fights her way inside.

As we near the lagoon, the force of the current slackens. The fisherman leads me between two bus-sized coral heads awash at the lagoon’s surface, and toward a calm spot out of the current, with an ideal depth for anchoring. I thank him profusely as he waves and speeds away. Dropping the anchor, I thank God, the Universe, the Cloud Goddess, Poseidon, my angels and whoever else might have helped this all work out so smoothly.

With survival temporarily off the checklist, I look around in awe. Palms sway over a small row of simple homes lining a white-sand beach, and the sea is as clear as a pool of Evian.

Clementine’s Island Tour

The next morning, as I tie the dinghy up to the quay of the tiny town, I’m greeted by a curious flock of kids. They squeak with delight at the chalk and jump-ropes I pull from my backpack, and I join three elderly ladies on a nearby bench to watch the children jump and draw on the cement landing area. The distinguished Puamotu dames are wearing handmade hats, each uniquely decorated, and they repeatedly ask me a question that I can’t understand.

“Ow est ton mari?” (Where’s your husband?)

I pull out my pocket dictionary. One of the women flips through and points. I read, “Mari (n, m), husband.” I laugh and finger through the English side of the dictionary to find “Alone (adj/adv), seul, seule, tout seul.”

“Je suis seule” (I am on my own), I tell them.

They squeal and pet me and squeeze my hands. Shaking their heads and holding their cheeks, they point to Swell and then back to me and talk quickly among themselves.

Before long, I set off to check out the tiny seaside village. I don’t make it far before a great round woman on an adult-sized tricycle approaches. I’m a bit intimidated at first, but as she gets closer, a wide smile spreads across her lovely Polynesian features. She stops and introduces herself as Clementine.

She motions repeatedly toward the large, low basket on the back of her bike, but I have no clue what she’s trying to tell me.

“IgiI” she says. “MonteI” (Here! Get on!)

I dig into my backpack for my dictionary again. She points to me and then to the basket, again and again. A little girl comes over and climbs into the basket, and holds onto Clementine’s shoulders to help her explain. They both point to me. The old ladies on the bench holler, “AllezI AllezI MonteI” (Go! Go! Get on!)

I hesitantly climb into the basket and take hold of Clementine’s shoulders. I don’t know what the plan is, but off we go as she presses casually on the pedals, hardly seeming to notice my weight. She points out the Catholic church, the elementary school, and the post office. As the dirt road veers left, my spontaneous tour guide waves to people tending their yards. The brightly colored homes are each uniquely decorated with shells and flowers and coconuts. Clementine swerves among kids playing marbles on the dirt roads, and two young girls soon join the tour on their bikes. Next, we pass the store, the town generator, and the Mormon and Protestant churches. It only takes us half an hour to ride through all the streets of the village. Then we pedal out to a coconut grove where Clementine’s mari is working. He’s the fisherman who had guided me into the pass! He opens us some fresh young coconuts to drink. As we sit under the swaying palms sipping nature’s most perfect refreshment, there’s nowhere I’d rather be. I’m in total disbelief at the kindness they’ve shown me. I cannot wait to write Barry about this.