Tasmania, Australia

As the water opens up ahead of us, and the landmasses grow fewer and further between, the distances between our destinations become ever longer. From Sulawesi in the north, we take a three-thousand-mile trip south across mainland Australia and down to Tasmania.

Many of the nations on our travels have contributed only a single word or two to our language. But in Australia – itself an Englishspeaking country, with long colonial ties to Britain – we’re once more spoilt for etymological choice.

Where is Tasmania, Australia? – Tasmania, Australia Map – Tasmania, Australia Map Download Free Photo Gallery

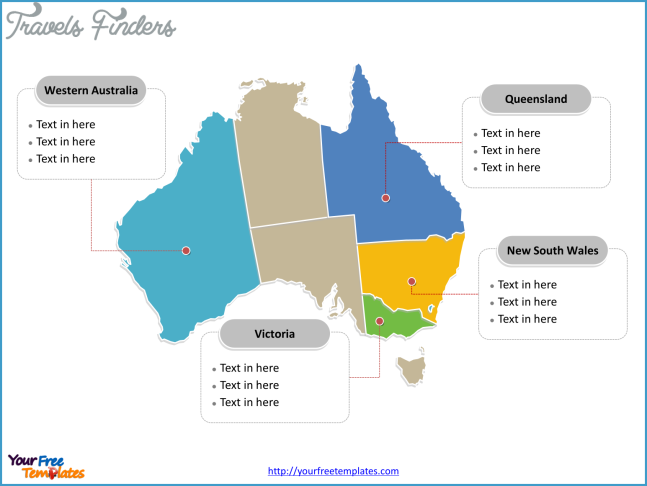

The town of Murrumbidgee in New South Wales, for example, is the origin of the expression Murrumbidgee whaler, a nineteenth-century nickname for an idler or slow worker. It derives from the local swagmen in the area, who would earn a living during only part of the year, selling fish caught using a hook and a length of twine:

Murrumbidgee whalers are a class of loafers who work for about six months in the year – i.e. during shearing and harvest – and camp the rest of the time in bends of rivers, and live by fishing and begging.

Also from New South Wales, the sydharb is a unit of capacity – often used to quantify the likes of floodwaters or reservoirs – equal to 500 billion litres, or the approximate volume of Sydney Harbour. And named after the address of the Supreme Court in Sydney, to go up King Street was a nineteenth-century euphemism for going bankrupt – the Australian version of London’s on Carey Street. The peach melba dessert famously takes its name from the acclaimed opera singer Dame Nellie Melba, but less well known is the fact that Dame Nellie in turn took her stage name from her place of birth: she was born Helen Porter Mitchell, in Melbourne – aka ‘Melba’ – in 1861.

A Queensland sore is a festering, poorly healing sore, once considered symptomatic of scurvy – a disease that required fresh fruit and vegetables, difficult to track down in the Australian outback, to remedy. The Queensland town of Moreton Bay became so known for the quality of its fig trees in the mid nineteenth century that Moreton Bay fig fell into use in Australian rhyming slang for a ‘fizgig’ – a sixteenth-century word that came to be used in criminal lingo for a police informant. All that had changed by the 1950s, however, as by then a Moreton Bay had morphed from an untrustworthy accomplice into a byword for a gullible fool, or the victim of a confidence trick.

As much as it might sound like a cheap pun, the so-called Coolgardie safe – a rudimentary device for keeping food cold in hot climates – was invented in the tiny isolated gold-rush town of Coolgardie, three hundred and fifty miles east of Perth, in the late 1890s. Little more than a miniature cupboard with water-soaked mesh or hessian for its door and sides, the Coolgardie kept the local prospectors’ food cool and guarded against insects in the fierce heat of the Australian outback.

While we’re in the outback, Min-Min lights are an eerie and unexplained phosphorescence that is said to follow lonely travellers around the remote Queensland desert. If not a word derived from some native Aboriginal language, the name Min-Min could simply derive from that of a hotel in the outback town of Boulia where the lights were first reported – though whether the lights or the hotel were named first is a mystery as difficult to solve as the lights themselves.

And the name of Tasmania’s River Derwent, on the banks of which was a notorious prison settlement, is the origin of an old nineteenth-century word, derwenter, for a released convict. But it’s another altogether more impressive-sounding word associated with Tasmania’s criminal past that concerns us now.

Beginning in the 1780s, Britain began using its recently acquired territories in Australia as the site of penal colonies, to which convicts – found guilty of anything from theft to bigamy – would be sent, often for years at a time. The first of these correctional colonies was established in New South Wales, but as they became full other sites began to be considered. In 1803, an expedition was sent to Tasmania to investigate the possibility of housing convicts offshore, and the following year a station was established at what would eventually grow to become the island’s capital, Hobart.

The transportation of convicts to New South Wales came to an end in the 1840s, after which the number of convicts being sent to Tasmania increased immensely; by the 1850s, the island was one of only a handful of penal colonies that remained active in the British Empire. This quickly established an association with all things criminal in Tasmania – a reputation that proved difficult to shift.

At the time, Tasmania wasn’t known as ‘Tasmania’, but rather as Van Diemen’s Land – a name bestowed on it by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, the first European to set foot on the island (and its eventual namesake). Tasman named the island in honour of his financial patron Anthony van Diemen, the Governor-General of the

Dutch East Indies, who in 1642 funded Tasman’s voyage around the Indian and western Pacific Oceans, during which the island was discovered.

Etymologically, that explains why a Vandemonian is an old-fashioned name for someone from Tasmania. Combined with Van Diemen’s Land’s long-standing association with criminality, it also explains the origin of the curious word vandemonianism:

Mr. Houston looked upon the conduct of hon. gentlemen opposite as ranging from the extreme of vandemonianism to the extreme of namby-pambyism.

According to Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words (1898), vandemonianism is ‘rowdy conduct, like that of an escaped convict’; the change in the spelling of Diemen in the centre of the word is, according to another nineteenth-century dictionary of Slang and its Analogues Past and Present (1890), intended as ‘a glance at “demon”.’

Happily for the people of Tasmania (and, we can presume, the entirely innocent Anthony van Diemen), the word vandemonianism does not seem to have endured. After penal transportation fell out of favour in the British justice system in the late 1860s, the island’s association with crime and criminality dwindled. And after the name Tasmania was adopted in 1856, use of the word vandemonianism and its derivatives likewise vanished from the language.

All theft above the value of one shilling was at one point potentially punishable by transportation – as were such bizarre offences as carrying too many paying passengers in a riverboat, stealing another person’s post, burning clothes and uprooting trees. Transportation to the other side of the world might sound like an impossibly harsh sentence for such relatively petty crimes, but at a time when capital punishment was still retained for more serious crimes such as rape and murder, transportation was perceived as a more lenient, yet still punitive, punishment.