These large specimens of Encephalartos woodii, severely damaged by bark removal, were photographed in 1918 at Ngoye, Natal, the last specimens known in the wild.

Cycads, their ancient origins and their present precarious situation have attracted scientists to Kirstenbosch from the Garden’s establishment to the present day. Cycads are the oldest of seed plants, having survived three of the Earth’s mass extinction events, found through 280 million years of the fossil record. Globally, fewer than 400 species of cycad are still living. Perched as they are on the edge of extinction, most of South Africa’s 38 species are represented in the living collections established from 1913 by Harold Pearson, nurtured by John Winter and Dickie Bowler and studied exhaustively by John Donaldson and colleagues.

John Donaldson, head of SANBI’s Applied Biodiversity Research Programme based at the KRC, is a world authority on the biology and conservation of cycads. As Chairman of the IUCN Cycad Specialist Group, and Chair of the IUCN/SSC Plants Committee, he is well placed to appreciate the crisis faced by this charismatic group of living fossils. South Africa is one of the global hot spots of cycad diversity, with 68 per cent of its 38 species threatened with extinction and three of these listed as Extinct in the Wild – just a short step from oblivion.

Most of South Africa’s cycads are being driven towards extinction by illegal trade. These confiscated plants have been donated to the NBGs for use in SANBI’s species recovery projects.

Unlike the majority of South Africa’s threatened species, which have been reduced through land transformation and habitat loss, the precarious status of cycads exists because of illegal trade. Thousands of cycads end up in the hands of private collectors, prepared to pay top prices to augment their collections. In addition, the stripping of bark for traditional medicine has led to the complete loss of populations of some species in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape. Despite the efforts by IUCN and conservation scientists, the best efforts have been futile, serving only to document what is a botanical disaster and a national disgrace. Species such as Encephalartos inopinus have been monitored by conservation authorities in Limpopo since 1992. They have recorded this species’ decline from 677 specimens in 1992 down to 81 in 2004 and there are unsubstantiated reports that the species might now be Extinct in the Wild. A classic case of going, going, gone.

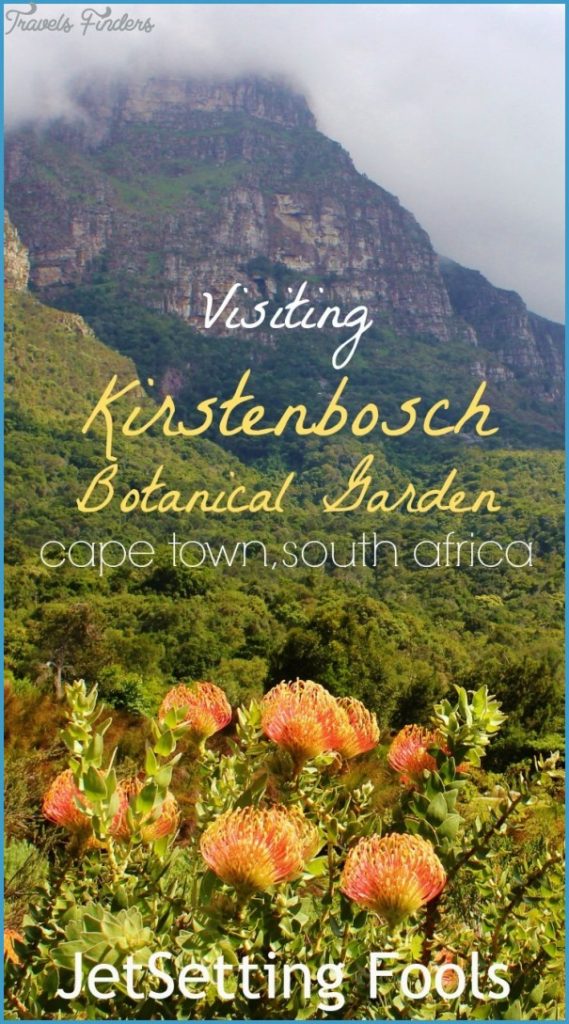

How To Plan A Trip To Kirstenbosch Photo Gallery

Now extinct in the wild, Encepharlartos woodii survives in many botanical gardens, but because only male plants have ever been found, vegetative propagation from suckers is the only option for expanding the living collection.

Despite these healthy male cones of Wood’s Cycad Encephalartos woodii, seed propagation of this species is impossible as no female plants exist.

Fortunately, SANBI has, within its network of gardens, a diverse gene bank of specimens that can be used in captive breeding’ programmes, possibly leading to their eventual re-establishment in their former habitats. But, as John Donaldson’s research has shown, cycads are dependent on symbiotic relationships with insect pollinators, algal nitrogen fixers and mammal dispersers of their seeds to maintain their populations. Restoration projects are far more complex than merely planting nursery-grown specimens back in the wild. Cycads remain the most critically threatened plant group in the world.

What had been an overgrown thicket of poplars, brambles and acacias in 1913 has been transformed into a cycad grove backed by a forest of indigenous Real Yellowwood Podocarpus latifolius, Small-leaved Yellowwood Podocarpus falcatus, Mountain Cedar Widdringtonia nodiflora and Cape Holly Ilex mitis.

The Kirstenbosch smoke primer The Kirstenbosch seed primer is a clever innovation for enhancing seed germination. A simple device, adaptedfrom a smoker for smoking trout, was used to collect the molecules emittedfrom veldfires for seed germination studies.

The Restio trial beds have proved to be a great success: the robust Cannomois grandis seen here is excellent for landscaping.

Research is often a serendipitous endeavour. Lord Rutherford is quoted as having said that you can plan research, but you cannot plan discovery’. Such was the experience of Hannes de Lange, who in 1988 joined the Threatened Plants Laboratory established in Kirstenbosch that year by Kobus Eloff. De Lange set about studying the life history of restios, a key fynbos family, but one that had defied propagation for use in horticulture. Careful field observations convinced De Lange that the fires that characterise fynbos ecological processes must have a role in the germination of the abundant seeds produced by the 314 species in the restio family. He experimented with combinations of heat intensity and frequency, different ash loads, both in the laboratory and in the field, burning patches of veld at different seasons and in different fynbos communities – but nothing would induce the tiny restio nuts to germinate. In desperation he wondered whether the smoke billowing forth from veld fires might play a role in the process. He set up a simple device, adapted from a smoker used to smoke trout, and subjected seeds to the passage of smoke from the kindling of fynbos plants. Eureka! – within a few days the seeds germinated. From a near-to-zero germination rate, De Lange was obtaining over 90 per cent success for many of the restio species, and for many other fynbos plants that had previously been impossible to propagate. News of his success spread like the very wildfire that was the key to his idea, and, very soon, Australian researchers at Kirstenbosch’s sister garden at King’s Park in Perth had isolated the active chemicals involved in the process. Ever innovative, Hannes de Lange produced a most practical way of exploiting his discovery. By pumping smoke through a water bath, soaking filter papers in the water and then drying them, he was able to store the active compound for future use. He packaged the filter papers and distributed them as the Kirstenbosch Primer’. Gardeners needed only to wet the paper in a plate or Petri dish, place seeds on the damp, smoke-primed surface, and wait for them to germinate.