New York Survival in the City

From the earliest days, migrants have resorted to ethnic group solidarity to find ways of surviving in the metropolis. For those who established communities in New York City before the era of government assistance programs such as public housing, welfare, Medicaid, and food stamps solving basic problems in times of crisis was less difficult if they had the support of relatives and of religious and

Star Kids, Children March in Puerto Rican Day Parade, New York City, 2006. Courtesy of Clarisel Gonzalez.

communal organizations. Mutual aid societies were organized at the workplace; and hometown clubs for people who shared a common place of origin are examples of associations that created a sort of social safety net to help weather personal and family episodes of hunger, sickness, or death. As early as the mid-1920s, 43 associations represented the various groups and interests of the Latino communities in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Most ethnic organizations identified themselves with a common Hispanic label, but many others were linked to specific nationalities for example, Puerto Rican, Spanish, Cuban, Venezuelan, Colombian, and Mexican. Since the 1920s, nonprofit organizations have proliferated and consolidated in federations and confederations, such as the Hispanic Federation, which alone encompasses no less than 80 organizations.7

Although many Latinos have realized their dreams of material, social, and intellectual improvement, New York City has always offered a tough challenge. To those with the least resources, to the weak of will, or to the plainly unlucky, New York City has embodied an insurmountable barrier, and for too many willing and able Latinos, their existence in that city has been reduced to mere survival. Wages for most Latinos in blue-collar occupations have always lagged behind the cost of

living in this perennially expensive city. A mixture of discrimination, lack of upwardly social connections, and insufficient schooling explain today as in yesteryears the high unemployment rate among Latinos, which have historically run at about twice the rate for whites. Latinos suffered massive unemployment on a few occasions, the Great Depression being the longest bout. So deep was the crisis that this was the only period in the twentieth century in which the number of Latinos, especially Puerto Ricans, returning to their lands of origin surpassed that of those arriving in New York City.

When New York City ceased being the industrial capital of the nation and metamorphosed into a center of national and international finance, insurance, real estate, and commerce in short, when it became a services-based economy most Latinos were ill-prepared to take advantage of the transition. At a slow but sustained pace, starting after World War II, the industrial base of New York was dismantled and moved increasingly farther from New York City. Just in the period 1950-1976, the city’s manufacturing jobs fell by almost 50 percent, from 1,038,900 to 527,000. The toll on Puerto Ricans was enormous, for two-thirds of them held blue-collar jobs at the time.8 On the other hand the new service economy created enough jobs to compensate for those lost in traditional industries, with the caveat that most service jobs paid less and offered no stability or benefits such as health insurance or pension. In addition, the well-paying jobs among the new employment opportunities went to those who had the skills and academic credentials to perform them.

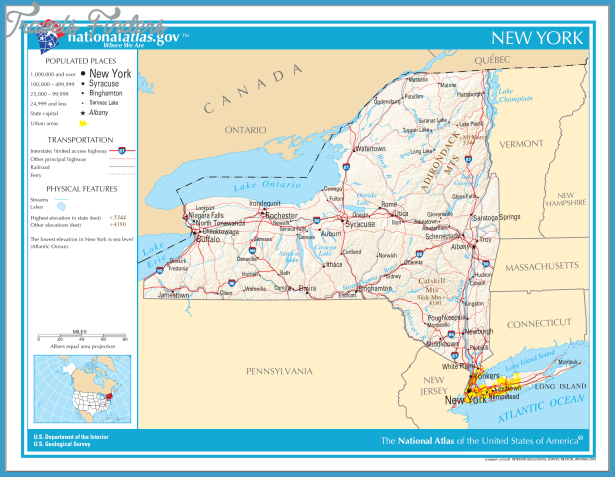

Because most Puerto Ricans lacked training beyond high school and many did not meet even this minimum requirement, they had to scramble for the few remaining manufacturing jobs, settle for occupations in the lower tiers of the service economy, or they were simply left jobless. The more recent migrants had it worse than the Puerto Ricans, for among them the noncitizens and undocumented were numerous, and they lacked English-language skills. New York City’s economic transformation lies at the root of many Latinos’ decision to leave that city in pursuit of those companies that relocated upstate, out of the state, or to Long Island, attracted by lower costs of land and labor, lower taxes, and fewer regulations.