New Zealand vines in their climates and soils

Viewed from the vine’s perspective it is limiting, although often necessary, to separate climate from soils when trying to understand why vines are cultivated by people in particular localities and regions. Grapevines have their roots in the soil and their leaves in the atmosphere. The plant reacts to stimuli from its total environment as it proceeds each year towards its biological imperative of producing fruit and seeds that will ripen, be eaten by birds and other animals, and reproduce the parent plant.

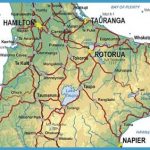

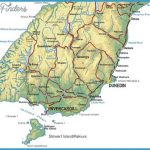

In the spirit of this integrated or eco-physiological approach, I begin by associating the regional pattern of vineyards in New Zealand with the precipitation they receive annually and the broad categories of terrain and soils they occupy, by using a map of the location of Quaternary sediments. Maps of the thermal environment of the vine are then used to tease out the components of cool climates in the localities and regions of New Zealand. Using

Maps New Zealand Photo Gallery

The New Zealand vineyard mapped alongside Quaternary sediments and precipitation the evidence of the last two decades, it is now possible to identify the particular characteristics of the climate in the regions where different varieties of vines have become localised. Without the benefit of such hindsight, New Zealand grape growers and winemakers had to learn these lessons by trial and error.

Do the New Zealand regions colonised by the vine since 1960 have some common natural attributes for viticulture? The answer is a loud ‘yes’. All of them have temperatures during the growing season that are among the hottest in the country, their soils are made up mainly of coarser materials with gravels predominating, they have low annual rainfall, they are less humid than the rest of the country, and they mainly occupy land that is relatively flat, although always with hills nearby that are increasingly being planted in vines. To demonstrate these associations I first use three maps. Figure 4.3 shows the distribution of vines in 2010. Flanking it are two indicators of the natural environment – those parts of the country receiving less than 1000 millimetres of precipitation annually and the location of the Quaternary sediments.

Ninety per cent of the land in wine grapes receives less than 1000 millimetres of precipitation annually. Only three of the regions growing vines – Auckland, Gisborne and Nelson – receive more than 1000 millimetres. Two parts of those – a very small part of the Gisborne Plain and probably small parts of Waiheke Island in the Auckland region – also squeeze under the 1000-millimetre isohyet. In some winegrowing regions, annual precipitation is noticeably lower. Part of coastal Hawke’s Bay, the Wairau Plain, and much of the Canterbury Plains receive under 800 millimetres of rain annually, while much of Central Otago receives under 400 millimetres. Low rainfall, especially when it comes with low humidity, is an economic advantage for viticulture because it means lower probabilities of many diseases and reduced costs for disease control, although these benefits are offset by the necessity to irrigate, especially when the vines are young.