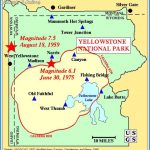

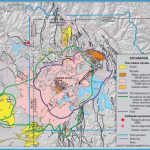

The road approaching Madison Junction from the west enters one of the major geological features of Yellowstone Park, the caldera, or huge crater, that formed 640,000 years ago. At that time, a vast volcanic explosion occurred, which blew out at least 1000 times as much rock as the Mount St. Helens eruption in Washington State did in 1980. The molten rock from a huge underground chamber was blown high into the air and then settled as volcanic ash (now called the Lava Creek tuff). The chamber extended from here east beyond the present-day Canyon Village and Fishing Bridge Junction areas and south almost to the edge of the park. Its boundary is shown by the dashed line on the map given to park visitors and on the map at the beginning of the Geological History chapter on 300. The ash settled out partly over the land north of here but was also carried to much of the northern Rockies and eastward to the Great Plains, as far as Iowa. So much rock was expelled, along with superheated water and other gases at high pressure, that the roof of this partly emptied chamber collapsed, leaving a large hole, the caldera.

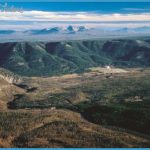

The volcanic activity did not cease after the ground collapsed inward. More molten rock rose into the chamber, forcing large volumes of thick, tacky lava out onto the caldera floor. The lava flows continued intermittently over the course of a few hundred thousand years, partly filling the caldera and building up a large, high flat area. This explains why today the caldera no longer appears like a hole or crater. The cliffs you can see across the river from the entrance road west of Madison Junction are a good example of these lava flows. Here they form the northern edge of the high flat area now called the Madison Plateau. The Madison Plateau reaches southwest approximately to the Idaho line, occupying 250 square miles (650 sq km) of territory. You can see good examples of its lava close up along the drive through Firehole River Canyon just south of Madison Junction.

The caldera is roughly oval, about 30 by 45 miles (48 by 72 km), and partly surrounded by cliffs, like a volcano’s crater but far larger. Cliffs extend along the road for about 8 miles (13 km) eastward past Madison Junction to Gibbon Falls, forming the northern wall of the caldera. Figure 1. Cross section of the Yellowstone caldera rim. This north-to-south cross section shows the northern rim of the Yellowstone caldera. When the Lava Creek tuff erupted and covered the older rocks 640,000 years ago, the ground surface then collapsed into the space left by the erupted tuff and so created the caldera. The arrows show the relative motion of the fault at the edge of the collapsed part. Rhyolite lavas later flowed out and covered the caldera floor. The dashed lines show approximately: (1) where the original caldera edge at the fault surface was before erosion and (2) where the surface of the tuff was outside the caldera before erosion.