The Post-Gadsden and Early Territorial Periods

Before Arizona became its own territory in 1863, it formed part of the territory of New Mexico, and the Mexicans who stayed there after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden Purchase became Arizona’s first ethnic Mexican citizens. Nevertheless, during the immediate post-Gadsden era, such categories were relatively fluid, as families continued to move freely between Arizona and Sonora. The two states worked as one social, cultural, and economic region, despite the international border that had recently separated them.

Sonoran politics was a key factor driving migration between Sonora and Arizona during the 1850s and 1860s. After Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna resigned, following the Mexican-American War, a succession of temporary governments divided Mexico into various liberal and conservative factions. In Sonora the struggle was between liberal Ignacio Pesqueira and conservative Manuel Marla Gandara, who had been a central figure in Sonora’s political infighting years earlier. They traded governance of the state several times during the 1850s and 1860s, until Porfirio Diaz became Mexico’s president in 1876 and installed his own governors. The battles between Pesqueira and Gandara, com-

bined with the French occupation of Sonora during the 1860s, led Sonorans to emigrate en masse, particularly between 1848 and 1849, 1852 and 1853, and 1865 and 1868.

Continued conflict with Native American groups in Sonora and Arizona also caused ethnic Mexicans in both states to migrate. As in earlier periods, Native American raids during the post-Gadsden era led farmers to abandon their land and move within and between Sonora and Arizona. Tensions caused by Anglo and Mexican conflicts with Native Americans increased during the 1850s and 1860s as Apaches and other Native Americans began to use the new international boundary to play each side against the other, participating in an illicit trade in arms, cattle, and other goods that had been stolen from the United States and Mexico. Anglos, Mexicans, and Pima and Tohono O’Odham Indians often formed alliances against Apaches; the most notorious example of such interethnic alliance was the Camp Grant Massacre of 1871, during which prominent Anglos, Mexicans, and Tohono O’odham from the Tucson area killed more than 100 Apaches, all but eight of whom were women and children.

Despite such tensions, Arizona’s mining, ranching, and agriculture industries developed significantly during the early territorial period, though they did not boom until the late nineteenth century (following technological developments such as the arrival of the railroad). Ever since Spanish explorers searched for Cibola during the sixteenth century and then struck silver at Arizonac in 1736, Arizona had been thought of in terms of its potential mineral wealth.

Shortly after the Gadsden Purchase, Anglo entrepreneurs reopened mines that had been dormant for decades. The Sonora Exploring and Mining Company, near Tubac, founded in 1856 by Charles D. Poston and Samuel P. Heintzelman, purchased property from Mexican landholders with backing from investors in New York, Ohio, and other states to the east. It was Arizona’s first mining corporation, though many others would follow. Mexican workersprimarily from Sonora, but also from Chihuahua, Durango, and Sinaloafilled most of the company’s labor needs, which included clearing out old abandoned shafts and digging new veins.

For 12-hour workdays, Mexican miners earned 16 ounces of flour and $15 to $30 per month, depending on the type of labor they performed. At the low end of the wage scale, pick and crowbar men (barrateros) and ore carriers (tanateros) earned $15 a month, whereas those who tended the furnace and smelters made $25 to $30. These wages were still higher than the $6 to $8 per month Mexican workers earned on haciendas in Sonora, though they earned only half the $30 to $70 per month that Anglo miners made.4 Most Anglo mine owners saw ethnic Mexicans as a cheap, efficient, docile, and permanent source of labor. One way they tried to make Mexican labor permanent was to charge a 300 percent markup on goods sold at the company store, which forced many to live month to month on lines of credit that bound them to the company. Nevertheless, many Mexicans

simply left the mines when they desired, or when they were mistreated, even if they owed money to the company store. Though many Mexican miners worked for Anglo-owned companies, some operated mines for themselves. One leased the Picacho Mine from Poston, and when he closed it during the 1860s (because heavy rains had flooded the mine shafts), Mexican gambusinos, or ore thieves, stayed behind and mined an additional 240,000 ounces of silver over several years.

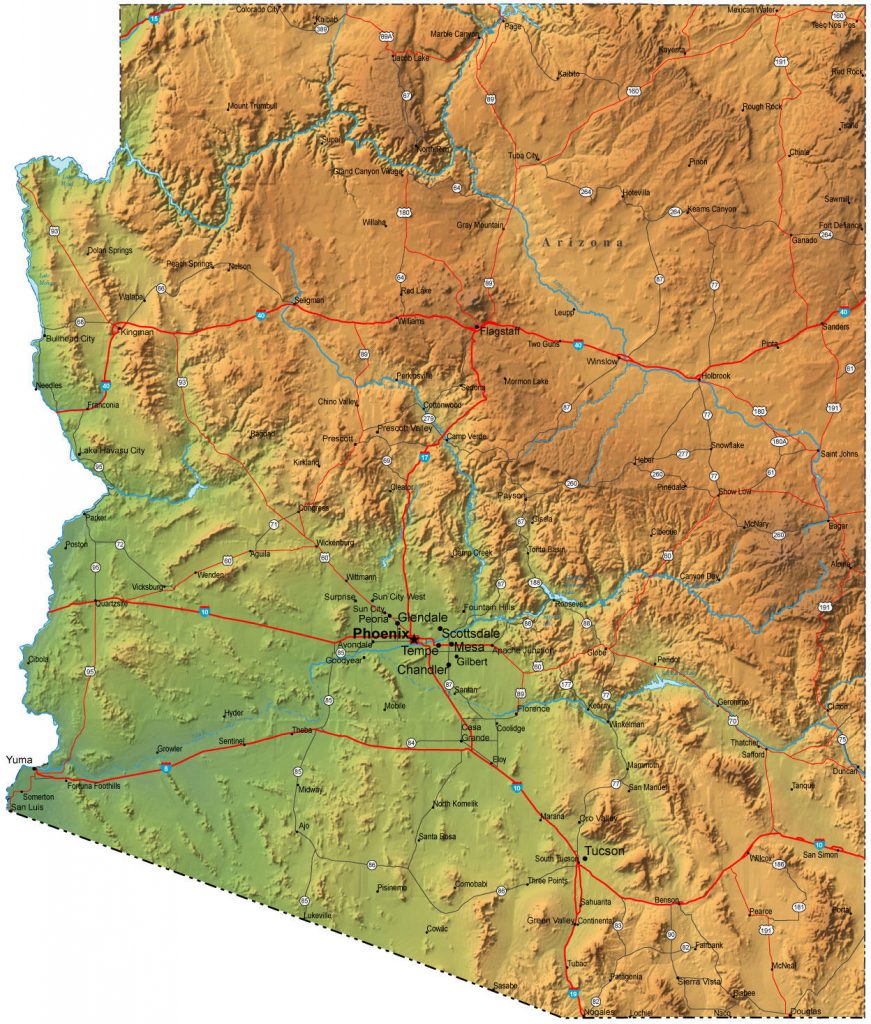

Far more common during the early territorial period than a relatively large operation such as the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company were the individual placer miners, or placeros, who traveled from camp to camp as various sites boomed and busted. They struck veins of ore, exhausted them, and moved on to the next strike. In general, mining progressed clockwise around the state, from Tubac to Yuma, to Wickenburg and Prescott, to Clifton and Morenci, and back down to Bisbee. Because of anti-Mexican racism in central and northern Arizona mining townsas well as long-standing cultural connections between Mexican miners and southern Arizonathe proportion of Mexican miners in Arizona decreased considerably as the mining frontier moved from south to north. Mexican and Mexican American men and women established camps that were generally separate from the camps of Anglo miners. According to the 1870 territorial census, the women were predominantly single and young; they were from Sonora, Arizona, and New Mexico, and they worked as cooks, housekeepers, boarding-room operators, and seamstresses.5