Shooting Star Wishes

I’m both nervous and excited about being alone at sea for my first significant ocean passage of five hundred miles to the remote atolls scattered to the south. As Hiva’s island shrinks into the distance, the sea welcomes me graciously small cumulus puffs drift west through blue skies with twelve to fifteen knots of wind flowing over my stern quarter.

I had raised the anchors at first light. With Hiva’s heart clearly growing fonder by the minute, it was time to move on. I’ve got a schedule to keep, with two friends and then a group of filmmakers joining me soon. I wrote Hiva a letter and gave it to another sailor in the bay to deliver. I hope he’ll be able to understand why I must go.

There is hardly any swell and the boat is well-balanced on a broad reach, so I decide to give the wind vane another try. The vane starts steering and doesn’t stop; the wing and gears and rudder are all moving in tandem, keeping us steadily on course. I celebrate with guavas and SAO, the local version of saltines. I’m thrilled that the Moniter wind vane is no longer just a fancy piece of stainless steel on the stern. I fine-tune the line that allows me to adjust our course from the head of the cockpit and give my new crew a name: Monita little monkey, like my Dad used to call me. He always said monkeys like me make great crew.

Surf Spot Locations, Maps and Information on Pacific Islands Photo Gallery

I buzz about making my floating home more functional. First, I saw down a piece of bamboo and lash it to the steering arch to make a holder for a rigging knife. Then I reinforce the lashings on the fishing reel strapped to the aft stanchion. Next, I screw down a drink holder beside the helm, and after studying my knot blog, I fashion a hanging rope sling for my little blue vase. I slip one of the gardenias that Hiva gave me into it.

I keep myself so busy that I hardly even think about being alone, but sailing solo has a few noticeable benefits. There’s only one place in the cockpit that’s always shady and dry and today, it’s all mine. I feel a bit more relaxed, too, knowing that if I screw up, my own life is the only one at stake. Oftentimes, I wish I had four hands: Alone, the boat jobs take a little longer and can be more complicated, but with ample patience and persistence there’s usually a way. When hoisting the outboard from the dinghy onto Swell’s stern bracket before a passage, I have to use my hands to heave on the davit line, while both my feet and teeth brace stabilizing ropes to keep the outboard from swinging around wildly as it rises.

The wind dies on the second day and I don’t turn on the engine even though I’m moving at only about two knots. Monita steers slowly through the brilliant fluorescent-blue sea. After some chores, I lay back, munch crackers, and watch the clouds. This solitude and speed are delightful a time and space of pure communion with the sea. Something I’ve long been thirsty for feels quenched, as if finally getting a moment alone with a long-time crush. This peace, this freedom it’s utterly satiating intense delicious! I can’t name or pinpoint it, but I’m sure it’s what keeps sailors returning to the sea. I soak it up, grateful for everything and everyone that led me to this moment.

This feeling must be the reason Barry never tired of being at sea. When I emailed to tell him that I wanted to try sailing solo, he was a bit surprised; I had been dead set against it before leaving. “It’s just something I feel the need to do,” I’d written to him.

“Then you must. I know you can do it. Prepare well, my girl, and remember to wear your harness,” he replied.

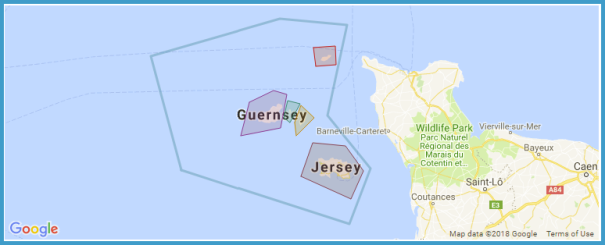

Although Barry had made local solo trips, he preferred sharing his mad love for being on the ocean. Over his forty-some years of sailing, he took innumerable guests out on his sailboats friends, family, colleagues, students, and perfect strangers on day trips, weekly afternoon races, sunset sails, weekend cruises, and hundreds of longer voyages along the California coast and to the Channel Islands. He even auctioned off trips aboard his boats to raise money for Jean’s tireless charity work, likely as a good excuse to go sailing. I know that he hoped to give all of his crew a taste of this wild, wonderful open-ocean feeling.

For four more carefree days, the sparkles of sunlight on my beloved sea are the only jewels I could ever want. Not too fast, not too slow. Nothing broken, nothing scary, nothing but the enjoyable side of sailing. I listen to music, write poems, do hand laundry, and nibble on fruits. And each night, Swell and I parallel the glowing stripe of the Milky Way overhead. Stargazing long hours from my cockpit bed, I think about the Cloud Goddess and send shooting star wishes to my family and friends; I don’t need anything else at the moment.

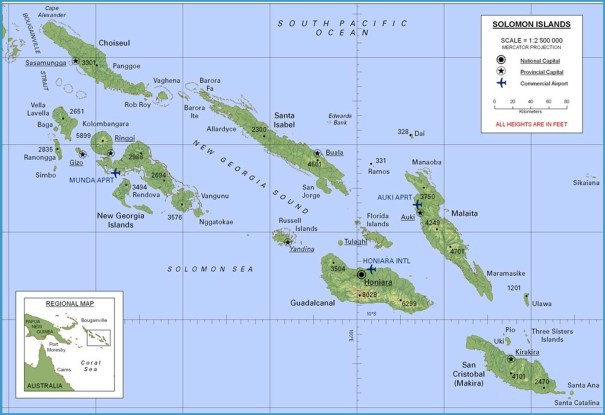

Then, as darkness falls on my fifth and final evening at sea, the wind abruptly switches 180 degrees. I spend the whole night tacking precariously between three unlit atolls, awaiting daylight to decide on my destination. Meanwhile, a nasty cold takes up residence in my sinuses. I check my position at least a hundred times, paranoid about getting too close to the long stretches of submerged reefs that helped earn this chain of atolls its nickname, The Dangerous Archipelago. Just before dawn I wipe my nose on my sleeve, and roll my eyes at the twelve-mile figure eight I sailed overnight.

The sun’s first rays light up a flat green patch of palms on an atoll up ahead. It was once an ancient volcanic island that now, over millions of years, has sunk back into the sea. Only the circular rim of the coral reef that once surrounded the island continues to grow toward the sea surface. Such ring-shaped atolls shelter an interior lagoon that can make for a protected anchorage if you can find a navigable entrance through the reef. I check the chart; finding no way in, we continue south. ZzzzzzzzzzzzzzI The fishing reel sings and I fight in my first fish of the passage a beautiful female mahi mahi. I see her mate trailing her and feel sad to take her. I must do this to eat. I reach out to gaff her, but she makes a final thrashing leap and shakes herself free. I’m actually relieved.

An hour later the line runs out again, harder this time, and ten minutes later, I haul aboard a gorgeous bigeye tuna. Something about being alone makes me feel more like an equal to this fish both of us just trying to survive on this wild, open sea.

I look into its wide black eye and almost throw it back, but instead, kneeling by its side, with my left hand gently resting on its opalescent flank, I say, “Thank you, beauty, for your life.”