From northerly perspectives, the antipodean Pacific remains a remote elsewhere, even if art from this region is institutionally badged’ with a certain Biennale Club Class’ look (Fuller, cited in Murray 2007). So pervasive is this new form of aesthetic colonialism that non-academically-trained Oceanic artists, particularly those of Melanesian heritage (read primitive’), have found less acceptance in global art environments attuned to conceptual art installations and screen-based media (Searle 2008). Visibility for Melanesian artists in Australia is nevertheless pertinent, considering the country’s proximity and intertwined histories with peoples of this region. Myriad connections include immigration, Queensland’s history of indentured labour (Moore 2001), World War Two operations (1942-45), Australian administration of Papua New Guinea (1945-72), foreign aid and tourism.

While New Zealand Pasifika artists, of predominantly Polynesian ancestry, are acclaimed at home in state and private galleries and enjoy moderate exposure at regional biennials and triennials,3 as well as Taiwan’s Art in the Contemporary Pacific projects at KMFA, these artists remain internationally under-exposed as evidenced in a number of targeted international group exhibitions, usually shown in natural history venues such as the University of Cambridge Museum (UK) or the Asia Society Museum (New York) (Tautai Contemporary Pacific Arts Trust 2011). As a minor part of its Asia-Pacific’ enterprise, QAG/GoMA’s Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) has exhibited a limited range of contemporary Oceanic art (mostly New Zealand-based) Pacific and Maori work (averaging between 12 and 25 per cent of total artists and/or exhibits)4 to global audiences and has acquired many works. Regionally, this neighbourly exposure has encouraged New Zealand and Island-based artists, but not wider international markets, for their work, which may be partly due to APT’s declining influence and it emphasis upon the performativity of Polynesian Pasifika. Australian Pacific art, however, remains a notable omission.

At a regional level, performance dominates pan-Pacific Melanesian Arts Festivals and peripatetic quadrennial Festivals of Pacific Arts (FPA), reinforcing the fluidity of Oceanic aesthetics and extending inter-island and global connections. Celebratory in nature, these events interlink individuals with communities in multi-sensorial and collaborative spectacles involving visuality, dance, song, oratory, story-telling and feasting, with a focus on sociality and conviviality. Here, despite increasing commercialization (Stevenson 2002), the contemporary jostles – and clashes – with ancient values, allowing renewal and reinvigoration (or rejection) of traditions. Pacific towns and cities are transformed temporarily through the influx of Oceanic communities and thousands of other international visitors experiencing alternative forms of cosmopolitanism’ in the South Seas. Significantly, long term benefits’ can accrue for FPA host centres as in Apia, (Western) Samoa, where the 1996 festival inaugurated the First Pacific Festival Contemporary Arts Exhibition and ensured continuation and strengthening of the Arts in Samoa for generations to come’ (Leahy et al. 2010: 27).

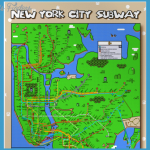

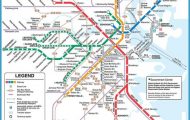

He left the BBC – the award to him of an Australia Subway Map Atlantic Award in Literature was under the condition that he gave up his job there – but continued Australia Subway Map to do freelance work for them, with his literary feature on the poet Ernest Dowson being broadcast at the very same time that his son David was born. He also continued to write poetry, and the Martello Bookshop published his collection entitled Poems From Rye with his acerbic comments about the constant stream of tourists in the town: ‘Through our streets the morons shamble asking for Woolworths