WILLIAM VAN ALEN

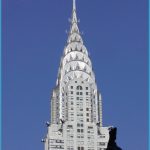

The world’s tallest tower at the time it was built, the Chrysler Building-commissioned by Chrysler to be their headquarters-is one of the most strikingly theatrical skyscrapers ever constructed. The 1,047-ft (319-m), 77-story structure is planned on a grand scale, rising from a broad, substantial base and becoming progressively narrower through the slender main tower to the unique spire that tapers to a point. The detailing is even bolder than the overall design-a series of flourishes, culminating in the famous spire, that mark out the architect, William Van Alen, as a great showman who was determined to make a building that would be instantly memorable and recognizable the world over.

Art Deco styling

The Chrysler Building is Art Deco in style. Art Deco took its name from the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, and it quickly caught on in both Europe and North America as a way of designing both buildings and items for the home. Art Deco was characterized by bright colors; bold, geometrical decorations; modern surface materials (from dazzling new metal alloys to colorful plastics); and motifs borrowed from ancient Egyptian art. All these elements appealed to architects, and Art Deco became particularly popular for showy, eye-catching buildings, such as cinemas, grand hotels, and skyscrapers.

Van Alen made extensive use of Art Deco details in the Chrysler Building. For the exterior he took motifs such as hubcaps and hood ornaments from cars built by Chrysler and adapted them to suit the architecture of the building. Inside, rich wood inlays and metal decorations make the lobbies and elevators some of the most memorable in Manhattan. Van Alen originally intended to increase his already lavish use of glass by topping the tower with a dome, but he soon changed his plans. While the tower was under construction, New York’s Bank of Manhattan building was completed at 927ft (282.5m)-about a yard taller than the Chrysler’s planned height-so Van Alen decided to replace the dome with a spire. The spire was prefabricated in four sections, which were hoisted into position on October 23, 1929, adding 121ft (37m) to the building’s height. The spire proved to be a masterstroke, a tapering structure made of a series of curves, each smaller than the one below. Clad in metal and with unusual triangular windows that shine like beacons at night, the spire resembles a series of sunbursts-another popular Art Deco motif.

By adding a spire to the Chrysler Building, Van Alen had designed not only the tallest tower in the world, but also the first man-made structure to top 1,000ft (305m). On a clear day visitors to the double-height observatory on the 71st floor could enjoy views of over 100 miles (161km). The Chrysler’s height alone was enough to make the building famous, but it was also a world leader in terms of modernity and efficiency. The 10,000 people who worked in the building were served by 32 high-speed elevators, and there was a state-of-the art vacuum cleaning system. The communal rooms were decorated with mirror-clad columns and had Art Deco aluminium furniture. Both inside and out, the Chrysler was the ultimate Art Deco building.

WILLIAM VAN ALEN

1883-1954

William Van Alen was born in Brooklyn, New York, and took night classes at the nearby Pratt Institute. He worked for several New York City architects on buildings in the city before winning a scholarship in 1908 to go to Paris, which enabled him to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. When he returned to the US, he set up in partnership with H Craig Severance, and the pair worked on a number of tall commercial buildings before they quarreled and parted company. When Van Alen, now working independently, began constructing the Chrysler Building, he found himself in a race with Severance to build the tallest skyscraper a race he eventually won. When the project was completed, however, Van Alen entered into dispute with his client, Walter Chrysler. The architect had no contract with Chrysler, and when he claimed his fee of six percent of the construction budget, the money was withheld. Van Alen sued Chrysler and won the case, but after such a high-profile conflict with an influential client, he found it difficult to obtain further work, especially during the Great Depression. Most of Van Alen’s estate was left to the independent architectural organization that now bears his name.

Visual tour

3 SETBACKS A visitor looking up at the tower from the main entrance is greeted by a symmetrical pattern of windows and a carefully arranged series of blocks. A few stories up in the center, the first setback (recession) gives a dramatic view of the tower, rising toward the sky. On either side the building tapers with further setbacks, so that sunlight can reach down to the frontages on 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue.

1 ORNAMENTATION The building’s unique decorative details include the stylized wing motif shown here, which is taken from Chrysler radiator caps. Another key element is a series of circles, based on Chrysler hubcaps, that run around the walls. These decorations not only made the building a successful advertisement for Chrysler automobiles, they also helped to set it apart from the white-walled austerity of modernism as well as the serious classicism of older buildings.

2 MAIN ENTRANCE Many Art Deco buildings use glass creatively, and the Chrysler Building is no exception. High windows above the main entrance light the lobby, and the glazing is arranged in relatively small panes, which create a pattern of rectangles and diagonals. On each side triangular panels in a zigzag design add to the effect, and the bright metal finish of the glazing bars harmonizes with the steel-edged entrance doors below. This entrance is designed to be equally impressive at night, when the number of the building stands out against a glowing background.

2 SPIRE DETAIL A late modification to increase the height of the tower, this glittering spire quickly became the most famous part of the building. Its distinctive tiers of shining crescents are clad in Nirosta stainless steel, which contains a percentage of nickel and chromium, making it weather-resistant, strong, and bright. Van Alen liked its low-maintenance properties, which ensured that the top of the building would shine brightly for many decades.

3 GARGOYLE Taking the form of giant eagle heads and clad in Nirosta stainless steel like the spire, a number of striking gargoyles jut out from the corners of the building. Streamlined in design, they are the Art Deco equivalent of the gargoyles on Gothic cathedrals (see p.75). Van Alen based the birds on the hood ornaments of the 1929 Plymouth automobiles manufactured by Chrysler. The gargoyles’ necks hold floodlights that illuminate the building at night.

IN CONTEXT

Skyscrapers tall buildings supported by a steel frame were first constructed in Chicago in the 1880s. By the beginning of the 20th century they had spread to other American cities, especially New York, where owners and developers saw two advantages to building tall: they could cram in more offices on expensive city-center sites and could use a tall building for publicity. Landmark New York skyscrapers included the Gothic-style Woolworth Building (1913, 791ft/241m) and the Empire State Building (1931, 1,453ft/443m).

1 ELEVATOR DOOR The lobbies are among the most luxurious areas of the building and have walls of red Moroccan marble designed to impress anyone entering the main door. The elevator doors are inlaid with rare woods, including Japanese ash and Asian walnut. The inlay creates curling scroll patterns, with a fanlike design at the top that was probably influenced by Egyptian lotus-flower motifs. Some elevators took just a minute to reach the top of the building.

1 Empire State Building, New York

For decades following its construction, this famous skyscraper remained the world’s tallest building.