Begun 1163

Transepts and choir finished 1182

Transept ends: Jean de Chelles and Pierre de Montereau, c.1250-60

Notre-Dame is, for me, one of the most pessimistic buildings in the world. Not from excessive gloom, which is always surmountable, but through an overpowering sense, outside and in, that God built Notre-Dame as he inscribed the tablets of Moses, then slammed the door shut to sit in judgement for ever and ever and ever. No hope of change, and no glimmer of ultimate purpose: just an endless office of worship like the Gregorian chant that always seems to be going on somewhere inside.

Notre Dame Paris

The possibility of artistic progression is as alien to Notre-Dame as it would be to a lump of Old Red Sandstone; it is there simply to uphold the Law, indifferent even to the kind of worship that goes on inside it: Pagan rites or streams of tourists? So much the worse for them God is just, and I can wait.’ To turn, inside, at the crossing and look at the ends of the transepts – which were built about 1250, almost a hundred years later than the rest – is like walking out into the sunshine. The huge rose windows and the nervous arcades underneath are alive, human, and fallible. In this case the fallibility leads to complete success, and boyish tiptoe stretching has created what a considered rational design never could: a circle which really fills the gable, makes it taller, makes it taller still with the fragility of the gallery of little gables underneath.

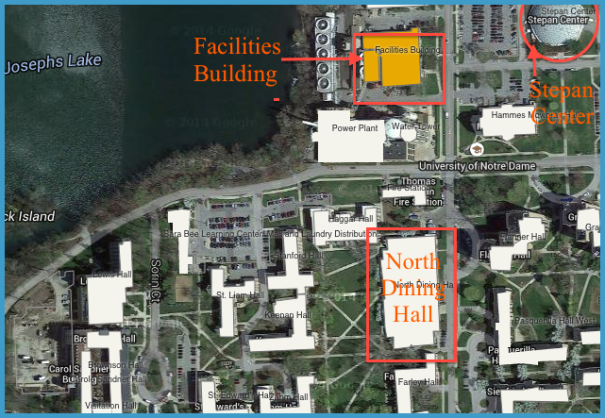

Notre Dame University

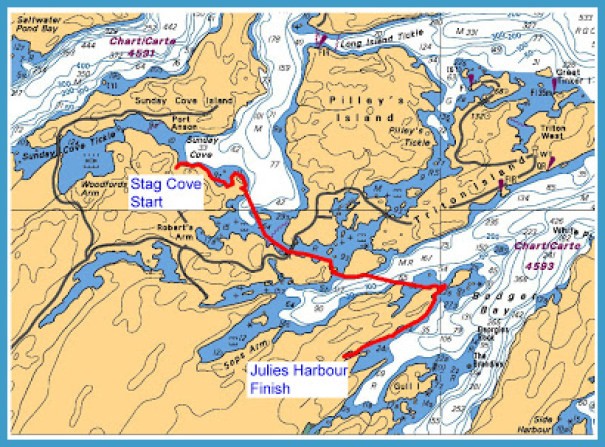

Notre Dame Island Map Photo Gallery

That is inside. Outside, the transepts are absorbed by the sluggish flow of Notre-Dame’s leaden skin. For Viollet-le-Duc’s musty and self-righteous cackle can be heard all over the building. Apart from a few tiny scenes around the borders of the main compositions, too minor to touch up, the sculpture just does not convince, even with Michelin’s admirable sorting out of what is obviously nineteenth-century and what is said to be medieval. The vignettes are vibrant, inhabited, like Goujon’s sculptures – and both are French first and attached to a monument in history second – the big scenes are cold bread-and-butter pudding. Not so Notre Dame de Paris’, the fourteenth-century statue inside, placed against the south-east pillar of the crossing, wide-eyed with rebellious hair. If she were not an object of veneration there might be some crisp Parisian jokes about her.

Notre Dame Athletics

Notre Dame de Paris is on the side of life. Notre-Dame the building – like Versailles – is not. But it is filled with a tremendous bleak force; the authentic Victorian father: Gladstone-les-Grandes-Terres. Begun in 1163, finished in effect by 1220, it took the Gothic structural discoveries and hit them for six. The extra freedom given by the pointed arch and the flying buttress was absorbed, understood – and then re-used to serve the old style, just as a reactionary politician might wolf a few progressive ideas. The deep galleries were kept, and used as instruments of darkness. The flying buttresses, the two rows of aisles and third row of chapels are all set out like a textblog of Gothic structure. It is a Romanesque building given an atomic warhead.

Notre Dame Admissions

Even in a blog made up of personal views, this is excessively personal. When my wife read it, she suggested that there was a nebulousness at the heart of Notre-Dame which would admit conflicting views (utterly different from the compassion at the heart of St Paul’s, which will embrace conflicting views). And that is undoubtedly true. Notre-Dame is cosmically equivocal, the each-way bet of the Sourire de Reims that goes so much deeper than mere shifiness. Born hermaphrodite, and for my money desexed altogether by Viollet-le-Duc, it hangs there with snake’s eyes; alert, yet indolent after eight centuries.