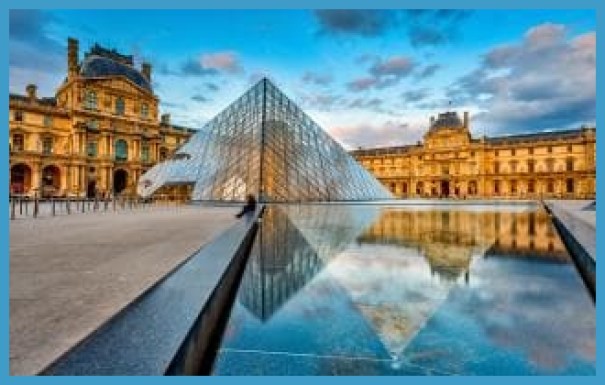

Louvre: colonnade

Claude Perrault, 1667-70

The buildings of Paris are plunging into an ordeal by cleaning which only the strongest will survive: to see what I mean, look at the newly scrubbed Hotel de Ville. Perrault’s front to the Louvre has come out unimpaired. And so it ought, for here is one of the masterpieces of the academic French temperament. Even-tempered to a fault’, they say. Well, this is even-tempered, or at least evenly balanced, to a superlative virtue. Like matter before we knew how to break the atom, it seems impossible to crack the unity symbolized by the noble cipher – L and L reversed -which recurs in each bay. Everything is attended to: build-up from wings to centre, continuity from end to end, balance of light and shade, matching of basement and roofline. The doctor-turned-architect designed this as though it were a perfectly functioning model of a body, homo sapiens without his aches and pains. Historically, he took Bernini’s grandiose idea and translated it.

Spiritually, he built for the autocrat of autocrats a handblog of Republican reason. Incisive yet supple, grand yet humane; the opposing adjectives form up two by two in an attempt to define this knife-edge of achievement.1

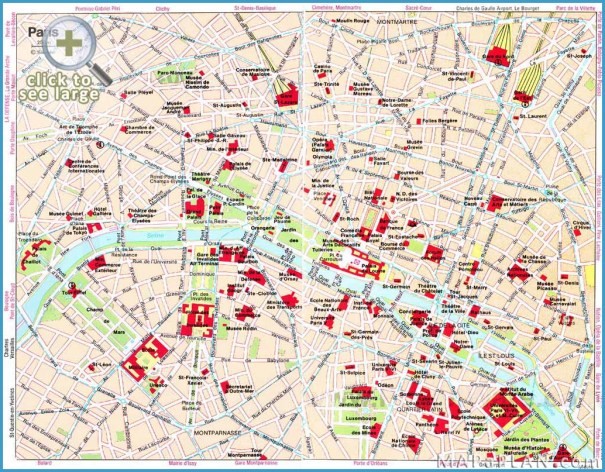

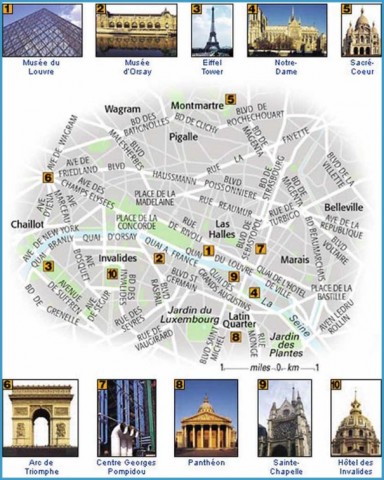

Places to visit and Tourist Attractions in Paris Photo Gallery

Behind Perrault’s facade is a huge mass of building which is just about enough to put anyone off architecture for good. Detail for its own sake, deployed over four centuries. In the vast three-storey courtyard, the original delicacy of Lescot and Goujon is lost in a welter of emulation; for the rest, there is a good deal of clever, concise architecture by Percier and Fontaine in the north wing, facing the rue de Rivoli. But who, faced with such an orgy of stonework, has the strength to discriminate?

Top Tourist Attractions in Paris

Louvre: collections

Galerie d’Apollon: Lebrun, begun 1663

Imagine the British Museum, V&A and National Gallery all crammed into Hampton Court and you have some idea of the scope and size of the Louvre. The only certain thing to be said about it is that you are likely to be exhausted by the end of the visit. The galleries themselves have the scale of a market or exchange, which is just as well, because the pressure of tourists is formidable – far more than in any London gallery. Somehow the buildings contain them, just as Paris itself does; and just when you feel that any more art will make you scream, a cafe turns up, fitted in on a landing of one of the staircases and running out into the open air along a balcony. Much of the building is itself good art, notably the Galerie d’Apollon, decorated by Lebrun c.1670, sturdier and grander than anything at Versailles.

Any attempt at detailed description would be a farce: the Louvre needs a blog to itself. All I can do is to give a short-list of things which I feel ought not to be missed on even the briefest visit: the Galerie Medicis, stuffed with Rubens’s overwhelming bounty, to the tune of twenty-one huge canvases commemorating Marie de Medicis, originally in the Luxembourg Palace; the nineteenth-century French painters on the second floor, including Corot’s Souvenir de Mortefontaine, which is not in the least sentimental, and a formidable Spanish portrait by Manet (Angelina); the sculpture gallery on the ground floor, with masterpieces from the Romanesque to Coysevox, and the formidably sombre tomb of Philippe Pot (made c.1480 and brought from Citeaux) carried by an unforgettable procession of hooded black mourners.

Finally, four separate masterpieces: Watteau’s famous Gilles, displaying a broken heart under an unbearably straight face, and Chardin’s La Raie, quite different from his normal unemotional still-lifes – the eerie fish wears an even more eerie grin, the kind of frisson provided in another way by Longhi’s masked figures. Both of these are in the rooms west of the Galerie Medicis. Rembrandt’s Flayed Ox, which could easily be missed, is in one of the small rooms north of the Galerie Medicis. And David’s Madame Recamier is perhaps the biggest surprise in the Louvre. It turns out to be a lively and sympathetic portrait, not the frigid neo-Classical piece that you might guess from reproductions – there are plenty of platitudes to check by in the same room, and some of them by David, too. It is a good human mascot to hang on to in this vast and bewildering pantechnicon of art.

Paris Tourist Attractions

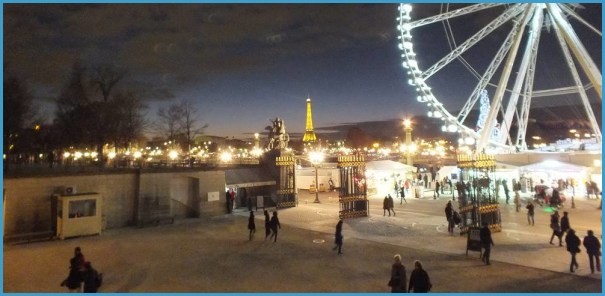

Jardin des Tuileries

The eastern end, next to the Louvre, is a mini-Versailles of formal planting; the western end, next to the Place de la Concorde, one of the most soothing places on earth. Nowhere else in Paris is the city’s uniqueness presented with such conviction. Because this end of the gardens is, simply, a gravelled space interrupted occasionally with grass and thickly planted with trees in a formal pattern. What’s special about that? The scale and compassion of the gesture, which supplies basic amenity as though it were food and drink and then leaves you free – really free – to enjoy it. These are enchanted groves for world-citizens, where each gesture has its own weight and space: absolute, unimpeded by any outside influence: assessed by its own nature and no other – whether it is a kiss or a system of philosophy. This apparent innocence is in fact the product of complete sophistication, the far end of experience where everything is real and new yet full of illusion and continually remembered. Not bad for a thick copse and some gravel; but that’s Paris.